Nobel Literature laureate Herta Muller never tried to hide her family’s Nazi history or to run away from the years she lived in a dictatorship. In fact, she draws on her past to voice her critiques of the present – and her concerns about Israel’s future

STOCKHOLM – Herta Muller, winner of the 2009 Nobel Prize in Literature, never tried to hide her family’s Nazi past or to run away from the years she lived in a dictatorship. Quite the opposite: As a child born to a father who had been a member of the Waffen-SS after World War II, who grew up in Communist Romania and suffered harassment, censorship and abuse at the hands of a totalitarian regime, she draws on her past experiences to critique the present and voice concerns about the future.

The Romanian-born German novelist, poet and essayist – renowned for her poignant explorations of oppression under Nicolae Ceausescu’s Communist regime – was the sole non-Jewish participant at the “October 7 Forum,” a two-day literary event organized by the Institution of Jewish Culture in Sweden, featuring the participation of academics, authors and journalists from Israel and other countries. On an unusually hot day for Stockholm in late May, Muller said she felt “a need, a commitment, an obligation” to be in the hall filled with hundreds at the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts.

In the speech she delivered, entitled “I Can’t Imagine the World Without Israel,” and in an interview with Haaretz, Muller unapologetically draws comparisons between the atrocities of the Nazis and those of Hamas, and expresses alarm in the face of what she describes as the global left’s silence over the events of October 7. As she sees it, these are both symptoms of a broader retreat from democratic values in the West.

Israel At War: Get a daily summary

direct to your inbox

Why was it important for you, a non-Jewish writer, to be part of this Jewish forum?

“I grew up in a dictatorship in Romania and the reality I lived in politicized me. I was forced to think politically. I was drawn to art and literature because I wanted to understand how one could live without becoming guilty, without losing oneself, and without endangering others. For decades, I saw how fear operates.

“When I started reading books around the age of 15, one of the school books included Paul Celan’s ‘Death Fugue,’” she continues, referring to a German-language work (original title “Todesfuge”) written by the Romanian-born Celan around 1945 and published in 1948. It is one of the first published poems about the experiences of Jews in Nazi concentration camps and is today recognized as a benchmark of 20th-century European poetry about the Holocaust.

Related Articles

Worried about rising antisemitism? A pro-Israel musical by Nazi descendants might help

This Holocaust narrative forces Israelis to settle for less

The Hamas pogrom demonstrates that Zionism has failed, says historian Moshe Zimmermann

“The poem was included in the book, but they didn’t mention that Celan’s parents were murdered in a camp under Romanian leadership. There was always this duplicity in my life. “

Censored and fired

Muller grew up in Nitzkydorf, a German-speaking village in Romania, where she was born in 1950. Before that, her father had served in the Waffen-SS; her mother was deported to a forced labor camp in the Soviet Union in 1945, among the 100,000 members of the German minority deported to such camps, from which she was released five years later. During her university years, Muller opposed Nicolae Ceausescu’s regime and joined Aktionsgruppe Banat, a group of dissident writers advocating for freedom of expression. In 1982, while working as a translator in a factory, she wrote her first collection of short stories. The Romanian authorities censored the stories and Muller was dismissed from her job after refusing to collaborate with the Securitate secret police.

The uncensored version of “Niederungen,” a largely autobiographical work depicting the life of peasants of German descent, would be published in Germany two years later and receive praise. Her later novels, such as “The Land of Green Plums” and “The Appointment,” use allegory to portray the harsh realities endured by ordinary people under totalitarian rule.

Due to her refusal to collaborate with the Communist regime, Muller’s works were censored, she was persecuted and she was denied an exit visa until finally being allowed to emigrate to West Germany in 1987, where she has continued her struggle to emphasize the importance of free speech and the perils of totalitarianism – the focus of many of her works.

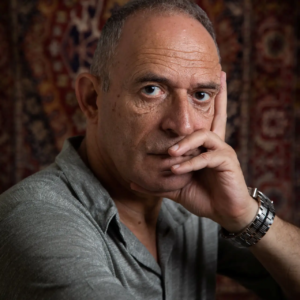

Today, Muller, a petite woman with a sharp black bob and expressive blue eyes, conveys complex emotions vividly with her words. She describes the constant fear ordinary citizens experienced under Ceausescu’s regime, from 1967 until 1989, and the pervasive “antisemitism and the anxiety that came with it, as antisemitism was always part of the dictatorship.”

In Muller’s youth, the Romanian government, aligning itself with the official stance of the Soviet Union and other Eastern Bloc countries, adopted a staunch anti-Zionist approach, viewing the movement as a form of bourgeois nationalism and a threat to socialist unity. One of the most notable aspects of Ceausescu’s antisemitic policies was his regime’s use of Jewish emigration as a revenue source: Ceausescu allowed Jews to emigrate to Israel in exchange for significant payments from the Israeli government and Jewish organizations.

“Because Israel is and always was threatened, this fear is ever-present, always dominant. After October 7, this plunged me into horror,” Muller, who visited Israel once, in 2015, tells Haaretz. “It is as if reason was blown away, and the actors continue without reason, driven by animalistic hatred. I feel compelled to do something, but I can’t. I have no other option than to express how outrageous this is.”

Muller, in her speech, recounted the horror of seeing images of people celebrating the October 7 massacre in Berlin: “Palestinian Hamas terrorists carried out an unimaginable massacre in Israel… Their victory celebrations continued back home in Gaza, where the terrorists dragged badly abused hostages and presented them as spoils of war to the cheering population. This macabre celebration extended to Berlin. In Neukolln, people danced in the streets and the Palestinian organization Samidoun handed out sweets. The internet was buzzing with happy comments…

“This massacre follows the pattern of annihilation through pogroms, a pattern that Jews have known for centuries. That is why it traumatized the entire country, because by founding the State of Israel the Jews wanted to protect themselves from such pogroms. And until October 7 they believed they were protected.”

Muller says that since the war broke out, she has constantly been reminded of “Ordinary Men,” the 1992 book by Christopher R. Browning. The book describes the annihilation of Jewish villages in Poland by the German Reserve Police Battalion 110 even before the large gas chambers and crematoria in Auschwitz were built. “It was like the bloodlust of the Hamas terrorists at the music festival and in the kibbutzim. In just one day in July 1942, the 1,500 Jewish residents were slaughtered in the village of Jozefow. Children and babies were shot in the street in front of the houses, the old and the sick in their beds. Everyone else was driven into the forest, made to undress and crawl naked on the ground.

Netanyahu vs. Ceausescu

Muller seems especially disappointed in two young progressive, liberal groups: Berlin club-goers and Ivy league students. “Hatred of Jews has eaten into Berlin’s nightlife,” she says. “After October 7, the Berlin club scene literally ducked away. Although 364 young people, ravers like them, were massacred at a techno festival, the club association did not comment on it until days later. And even that was just a dull exercise in compulsory action, because antisemitism and Hamas were not even mentioned.”

As a person who grew up in a dictatorship, she says she assumed that “in democracies, you learn to think individually because the individual counts, in contrast to a dictatorship, where your own thinking is forbidden and the coercive collective tames people.”

That’s why she is “appalled” by “young people, students in the West in particular, who are so confused that they are no longer aware of their freedom. That they seem to have lost the ability to distinguish between democracy and dictatorship.” The American students at pro-Palestinian demonstrations, Muller adds, “seem to endorse violence. The massacre of October 7 is not mentioned at all at these demonstrations, or it is presented as an Israeli staging; not a word is said to demand the release of the Israeli hostages. Instead, Israel’s war in Gaza is portrayed as an arbitrary war of conquest and annihilation by a colonial power.”

While acknowledging your support for Israel, do you have any criticism of the country’s leadership? Many Israelis who oppose Netanyahu’s rule and the judicial overhaul he promoted have compared him to Ceausescu. What do you think of that? Also, what are your thoughts on the treatment of Palestinians, the ongoing occupation of the West Bank and the conduct of the war in Gaza?

“I think it’s a tragic coincidence that Israel has to fight for its right to exist with a prime minister who wants to secure his political survival by any means possible. It is only for this reason that he has entered into a scandalous government coalition with extremists. This is a great misfortune for the whole country.

“But Netanyahu cannot be compared to Ceausescu and his dictatorship. In Israel, thousands of people took to the streets for months to demonstrate against the so-called judicial reform. They openly and vehemently demanded an independent judiciary and Netanyahu’s resignation. In Romania, people were sent to prison for every hint of criticism …

“Netanyahu may be corrupt and power-hungry, but Israel is still a democracy. There will be real elections – not sham elections like in dictatorships. And that means the Israeli people can vote him out. And they’ll probably vote him out because he and his scandalous government made serious mistakes for which Israel is now paying dearly.

“He completely misjudged Hamas. He thought he could tame it. In short, he strengthened it in order to weaken [Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud] Abbas. Apparently, Netanyahu is only clever when it comes to his personal security. In any case, he has lost sight of the Gaza Strip and has only focused on the settlers in the West Bank.

‘Turning heads’

Muller also addresses the impact of internet culture on young people’s perceptions of the war: “Are all the clips on TikTok popping into young people’s heads? The terms follower, influencer and activist no longer seem harmless to me. These smooth internet words are serious. They all existed before the internet. I translate them back in time, and suddenly they become as rigid as steel and overly clear… followers, agents of influence… as if they had been taken from the training grounds of a fascist or Communist dictatorship… They promote opportunism and obedience in the collective and spare people from having to take personal responsibility for what the group does.”

She also highlights social media as a driving force behind the growing surge of antisemitism: “Since October 7, antisemitism has spread as if by a collective snap of the fingers, as if Hamas were the influencer and the students were the followers. In the media world of influencers and their followers, only the short clicks on the videos count. The blink of an eye, the touch of lively emotions. The same trick works here as in advertising. Is the susceptibility of the masses, the reason for the disaster of the 20th century, taking a new turn? Complicated content, nuances, connections and contradictions, compromises are alien to the media world.”

Why do you think this is happening and do you feel that the West is moving toward becoming a less democratic society?

“This is happening almost everywhere – in Europe, in the United States. It’s tragic that in free societies like those in Western Europe and the United States, people no longer make the distinction between democracy and other forms of government. These societies are mentally deteriorating and becoming rundown. Free societies in the United States and Europe are dismantling themselves, eroding reason and rationality. These democracies are self-destructing, just as the United States would self-destruct if Trump were to win the elections again.”

What do you envision for the future of Israel?

“I hope that the diabolical antisemitism spreading across the world at the moment will eventually turn around and [the situation will] become rational again. Terrible dictatorships are ahead of us that question us as individuals. When Iran, China, Russia, Putin, Khamenei and Trump decide the politics, where do we live then? I fear that because I know what dictatorship means. My hope is that this existential fear and threat will be overcome and that people will come to their senses, and reason will prevail again.

“We need Israel. I often think that people supporting BDS are not dependent on Israel. They live in the USA, in Europe, in Paris or in Berlin… Boycotting and protesting without understanding is dangerous.

“There is a German saying that Heimat (homeland) is in the language, but it’s not true. Language is not a home. You carry language in your head, whether you want to or not. Only when you are dead do you lose it. But you need to be physically present somewhere as well.”