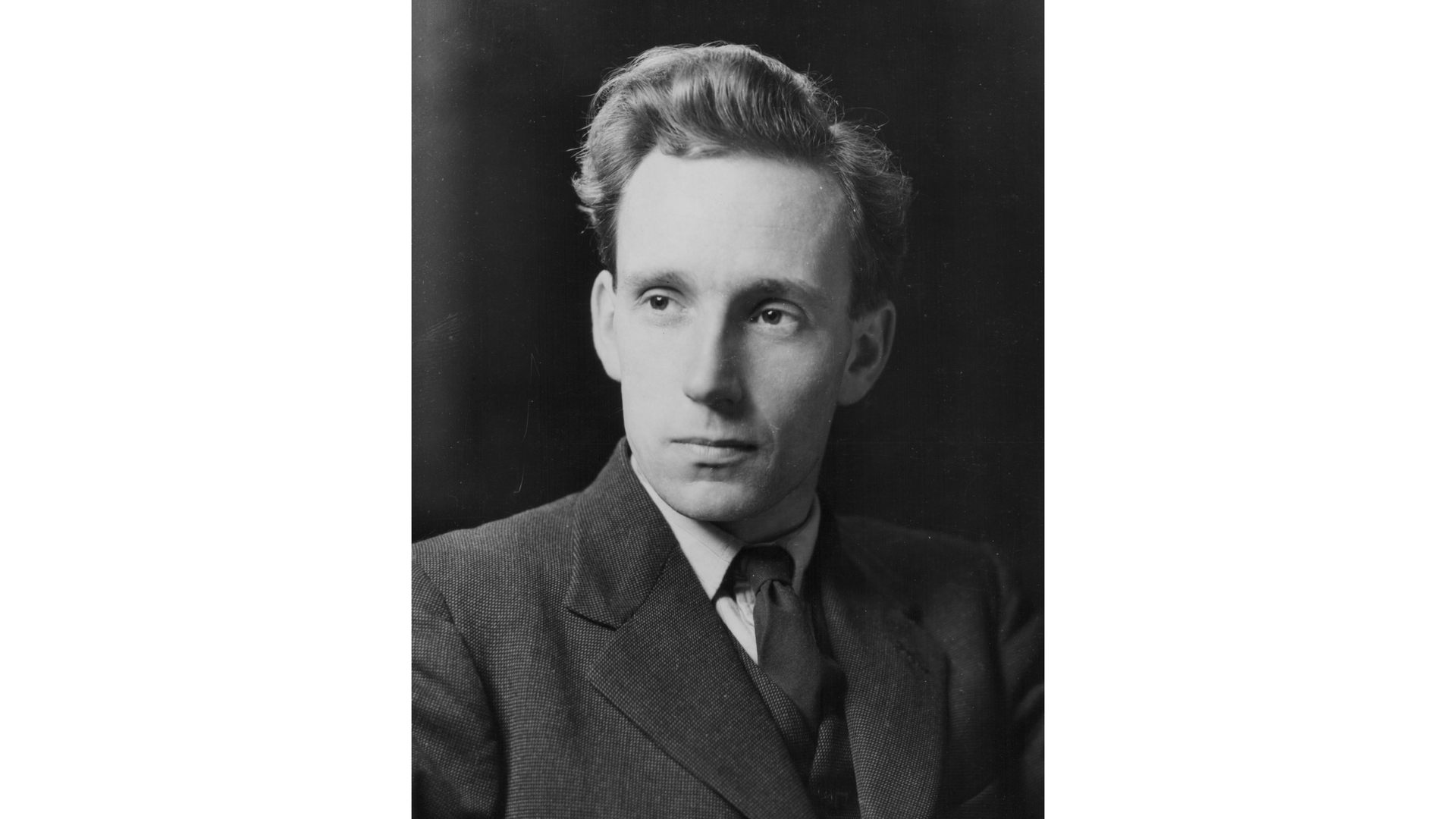

Last Saturday saw the departure of one of the last remaining British giants of the post-war world. Sir Brian Urquhart — one of perhaps the three most influential people in the 75-year history of the United Nations, which he joined immediately after its creation following a highly distinguished war record — died just short of his 102nd birthday at his rural home in Massachusetts surrounded by his family.

He has been my friend and mentor for the last 30 years, and I have often been asked — including by some of the suitably laudatory obituarists of the past day — to explain how any man could inspire so much reverence, particularly working in such an environment. Across all divides and backgrounds, his appeal was almost universal. And his reputation within the UN is still utterly unmatched by anyone since he left it.

The answer is that he embodied a unique combination of qualities. He was imbued with integrity, ethical standards, courage and compassion. But at the same time, he had the acutest understanding of the harsh realities, practical constraints, and murky politicking that prevent international ideals from being put into practice. An idealist but far from starry-eyed. A moralist but the least self-righteous one imaginable. One of the world’s leading diplomats, but direct, sincere, irreverent, and unpretentious. His points were delivered in a manner that was often humorous, self-deprecating, and disarmingly modest. The result was that almost every interlocutor felt at ease and able to trust him.

Much of his energy over 40 years was devoted to the Middle East. While under no illusions about any Arab government or political movement, he did not hide his conviction that Israel’s attacks on its neighbours and, after 1967, its occupation of their lands, were far from justified. Yet many Israeli leaders, to their credit, were able to recognise his skill and sincerity, with Prime Minister Menachem Begin calling him ‘a man of valour’. A good example of how he operated can be seen from his first encounter with foreign minister Yitzhak Shamir in 1978. As a fighter in the terrorist group the Stern Gang, Shamir shared responsibility for the assassination of the first UN mediator in the region, the Swedish Count Bernadotte. Thirty years later, against the advice of friends in the Israeli Foreign Ministry, Urquhart felt compelled to bring up the matter. The gruff Shamir unwittingly made it easy for him. ‘Good day Mr Under Secretary-General, you are the first UN official I have ever dealt with.’ ‘On the contrary,’ responded Urquhart, ‘as you may recall, you certainly “dealt with” Count Bernadotte.’ ‘Ah,’ came the reply, ‘that was all a big mistake, and I’m glad you raised it, let me explain.’

Urquhart had by then worked his way up the ranks of the UN, playing a key role in countless global crises; developing the practice of peace-keeping; helping to establish the International Atomic Energy Authority; getting kidnapped and badly beaten in the Congo; and generally becoming the go-to person at the UN for world leaders to call on and consult on a wide range of issues.

Remarkably, he not only played a key role in the UN’s history, but was also by far the most important historian of the UN. With a beautiful prose style, he wrote major biographies of what he (and many others) considered the two greatest figures of the UN, Dag Hammarskjold and Ralph Bunche, a captivating memoir called A Life in Peace and War, and a number of shorter studies as well as articles for the New York Review of Books right up to his final decade.

Brought up in Dorset by a single mother with limited means (his painter father bicycled out of their lives when Brian was seven), Brian won scholarships to Westminster and Oxford. But before his final university year, he joined the army the day after war was declared in 1939. He suffered a desperate injury when his parachute failed to open (‘I realised things were going wrong when I started overtaking all the chaps who’d jumped out before me’). This led to 80 years of back pain. He is accurately depicted in the book and film about Arnhem, A Bridge too Far, as the young intelligence officer bravely speaking truth to power (a habit engrained in him). He repeatedly warned his outraged superior officers that they were heading for disaster if they proceeded with the airdrop because of the arrival of German panzer divisions. He saw active service in Sicily and North Africa and was the first Allied officer to enter the death camp of Bergen-Belsen.

Though Urquhart lived in America for 75 years, his accent remained resolutely that of a British officer of his time (epithets included). Every Memorial Day, he would don his medals (asked what they had been awarded for, ‘I think basically for just being a good chap’) and attend the service in a country churchyard full of gravestones of patriots killed in the wars of 1776 and 1812 against Britain. He stood alongside locals who recognised a much-loved neighbour and world war two ally, but had little knowledge of what he had actually done.

When he was 92, a stroke in Paris left him almost speechless. The morning before, I had invited him to speak to UN staff in Belgrade and he wowed them with his total recall and insights from the 1950s and 1960s. Many people might have felt tempted to call it a day at that point. Not Urquhart; in his indomitable way, with the support of his daughter Rachel, he started therapy, relearning — from scratch — the ability to speak.

He never lost his zest for keeping up with world events. Unfortunately, this wasn’t a great source of comfort for him, as he considered both Trump and Brexit to be historic regressions in all he had struggled for: working against nationalist prejudices for the common good, for effective multilateral organizations, for truth.

He was an accomplished oboist. He loved literature (the novels of Patrick O’Brian were favourites), art (he was on the board of the Metropolitan Museum for Modern Art), nature (roaming the hills around his Massachusetts home). Brian was a deeply loyal and caring friend. And he worshipped his unevenly tempered corgi, who was constantly told ‘Archie, my boy, what a noble fellow you are’.

But most of all he was — especially in retirement — a devoted family man, a beloved patriarchal rock to his 30 descendants and second wife of nearly 60 years, Sidney, famous for her beauty and a tolerance of pretentiousness that was even lower than Brian’s. They adored one another and sparred merrily. She survived him by just one day.