Summary

“We tried. We can look our kids in the eyes and say we did everything we can.” — American Climate Protester Timothy Martin1

“We’ve been protesting in the streets for 50 years now. We’ve been signing petitions for 50 years now. And our emissions are still rising. So, the time of nicely asking is just over.” — Dutch Climate Protester Sieger Sloot2

“As a climate activist, I would understand the climate crisis as the greatest human rights violation of all time in ecological terms. It’s a human, it’s a civil society crisis, it’s a justice crisis, it’s a human rights crisis.”

— German Climate Protester Luisa Neubauer3

Before the sun had risen over London on October 17, 2022, Morgan Trowland and Marcus Decker were climbing the cables of the Queen Elizabeth II Bridge.4 Supporters of the climate change advocacy group Just Stop Oil, Trowland and Decker scaled the bridge to protest and raise awareness about the failure of the United Kingdom’s government to stop licensing all new oil, gas, and coal projects. For 36 hours, they stayed atop the bridge, leading police to stop traffic across the bridge for the duration and causing major disruption in that part of the city.5 On October 18, they were arrested and later charged with causing a public nuisance.6In April 2023, Decker was sentenced to two years and seven months in prison. Trowland received a three-year sentence, reportedly the longest ever for a peaceful climate protest in the United Kingdom at the time and the equivalent of a month in prison for every hour he was on the bridge.7 They were convicted under section 78 of the UK’s contentious Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act of 2022 (PCSCA).8

Sadly, those record-breaking sentences have already been broken. On July 11, 2024, Roger Hallam, Daniel Shaw, Louise Lancaster, Lucia Whittaker De Abreu, and Cressida Gethin were found guilty of conspiring to cause a public nuisance for their involvement in a plan to block the M25 motorway in London. The law used against them was, as with Decker and Trowland, section 78 of the PCSCA. 9 On July 18, 2024, Judge Christopher Hehir imposed shockingly harsh sentences on all five defendants. He sentenced Shaw, Lancaster, Whittaker De Abreu, and Gethin to four-years in jail. 10 Hallam, perhaps the highest profile climate activist in the UK, was sentenced to an unprecedented five years in jail, in spite of the fact that he offered evidence that he only attended one Zoom meeting to discuss the protest. The judge noted that he considered Trowland and Decker’s sentences as a reference point.11

In the days following the sentences, more than 1,200 lawyers, celebrities, academics, and artists called for a meeting with the new Labour Party-appointed attorney-general to address the injustice of the sentences.12 Michel Forst, the UN’s special rapporteur on environmental defenders under the Aarhus Convention, attended parts of the trial and issued a statement shortly after the five activists received their sentences. “Today marks a dark day for peaceful environmental protest, the protection of environmental defenders and indeed anyone concerned with the exercise of their fundamental freedoms in the United Kingdom… Rulings like today’s set a very dangerous precedent, not just for environmental protest but any form of peaceful protest that may, at one point or another, not align with the interests of the government of the day.”13

The UK is not the only democratic country in which climate protesters are being given disproportionately long sentences. On August 27, 2024, a German court sentenced 65-year-old Winfried Lorenz to 22 months in prison without parole, for his involvement in a climate protest that blocked a road. It is believed to be the longest sentence ever imposed in Berlin against a climate activist.14 Following his sentencing, Lorenz stated, “We are facing the greatest crisis in human history and it is essential to protest against policies that are leading us into climate catastrophe.15

In Australia, Deanna “Violet” Coco became one of the first individuals to be sentenced under one of Australia’s new laws allowing for more severe penalties for demonstrations involving “vital infrastructure.”16 On April 13, 2022, Coco blocked just one of five lanes of traffic on the Sydney Harbour Bridge for a total of 28 minutes to demand that the Australian government take greater action on climate change.17 Following her arrest, Coco pled guilty to breaching traffic laws, lighting a flare, and disobeying police orders to move on — all non-violent offenses. Despite the short duration, the limited scope, and the peaceful nature of the demonstration, Coco was sentenced to 15 months in prison.18

On April 27, 2023, Timothy Martin and Joanna Smith staged a climate protest at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., spreading red and black paint on the protective case of a sculpture.19 Climate protests involving works of art have become increasingly common in Europe, with similar actions occurring in Germany, the United Kingdom, and Spain, among other countries.20 This form of protest, which generally is not intended to cause permanent damage to the art itself, has often resulted in charges of trespassing or causing damage to public work and been penalized by a modest fine and sometimes restitution. While Martin and Smith expected to face charges for their actions, the government response was far harsher than anticipated. Each was charged with two felonies: conspiracy to commit an offense against the United States and injury to a National Gallery of Art exhibit.

Timothy Martin and Joanna Smith at the National Gallery in Washington D.C. April 27, 2023. Credit: © Cece Russell-Jayne

They learned that, if they were convicted, they could face up to five years in prison and a fine of up to $250,000.21 In December 2023, Joanna Smith pled guilty to one count of causing injury to a National Gallery of Art exhibit. In April 2024, she was sentenced to 60 days of prison time, 24 months of supervised release, and 150 hours of community service. In addition, Smith must pay more than $7,000 for a court fee, a fine, and restitution to the National Gallery, and she is barred from entering Washington D.C. or any museum or monument for two years.22 Martin’s trial is scheduled for November 19, 2024.23

Many democracies rightly criticize authoritarian regimes for their crackdowns on freedom of expression, association, and assembly. Climate Rights International noted that the United States, United Kingdom, and other countries named in the report have a long history of expressing support for the internationally protected rights to freedom of expression and assembly, as well as criticizing crackdowns on peaceful protests in developing countries. For instance, the 2023 State Department reports criticized crackdowns on peaceful protests in Bangladesh and Cambodia. The U.K. has made strong statements about the importance of peaceful protests at the United Nations Human Rights Council as recently as March and July 2024.

The imposition of penalties disproportionate to any harm caused has a chilling effect on basic rights and is incompatible with states’ obligations under international human rights law, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which all of the countries cited in this report are parties.

Yet, some democratic countries are even taking measures designed to stop peaceful climate protests before they start. In June 2023, Simon Lachner was detained by police in the German state of Bavaria under a controversial Bavarian law that allows for preventative custody.24 He was detained before he left home to join the blocking of a thoroughfare to bring attention to climate change.25 In The Netherlands in January 2023, Sieger Sloot, a Dutch actor and climate activist, was detained two days before a scheduled Extinction Rebellion demonstration at The Hague that he had encouraged his followers on Twitter to join.26 In August 2023, he was convicted of sedition, a felony, for encouraging others to attend the protest, and sentenced to 60 hours of community service or 30 days in jail.27

In Germany and France, authorities have gone even further to prevent protests, through blanket bans on protests in certain areas and even attempts to disband or criminalize certain climate advocacy groups and the actions of their members. In December 2022, following peaceful protests at airports throughout the country, authorities in Munich, Germany issued a ban on all climate-related protests blocking “key roads” and other areas for thirty days.28 The airports had been specifically targeted for advocacy to protest artificially cheap travel by plane, and to call for more train options.29

Authorities have also targeted specific climate advocacy groups. Prosecutors in the German town of Neuruppin charged five members of the German climate protest group Last Generation with “forming a criminal organization” on May 23, 2024.30 Mirjam Herrmann, one of the activists charged, told the media, “This is the first time in German history that a climate protest group that uses measures of peaceful civil disobedience is charged as a criminal organization.”31 Green party members in Munich were divided on the handling of the Last Generation, acknowledging its radical practices but not reaching unanimity on categorizing the group as “criminal.”32

In France, the government ordered the disbandment of the advocacy group Soulèvements de la Terre (the Earth Uprisings) in June 2023.33 In August 2023, France’s Council of State Court suspended the decision, ruling that the disbanding order against the group would restrict activists’ freedom of assembly and that the government had failed to provide sufficient evidence that the organization was inciting violence during their demonstrations.34 France’s top administrative court ultimately overturned the ban in November 2023.35

Credit: © Kelly Sikkema, Unsplash

People around the world are increasingly engaging in various forms of protest and awareness raising as climate change unleashes an avalanche of devastating consequences. July 2024 was the fourteenth month in a row to be the hottest on record.36 Rising sea levels are threatening small island states, coastal towns and even major cities, erasing land, destroying infrastructure, and putting at risk the very existence of entire communities and states. Models estimate that 250 to 400 million people risk being displaced by 2100.37Extreme weather events, intensified by climate change, are resulting in more frequent and severe storms, wildfires, droughts, heat waves, and floods, wreaking havoc on lives and livelihoods.38 Ecosystems are under threat, risking the extinction of up to one million species, a risk that increases with each uptick of the global temperature.39 Agricultural systems are increasingly vulnerable, with food security becoming a major concern.40 Access to clean water is jeopardized and the health of our oceans is deteriorating.41 There is no hiding from climate change — its reach extends into every facet of our daily lives and is a threat to the human rights of present and future generations.

The urgency of the climate crisis, and growing frustration with the failure of their governments to act, is driving many to use protest to press for necessary change. This is especially true for younger people, who are growing up in a world of uncertainty, facing the consequences of decisions that threaten their right to a future. While they cannot afford to donate large sums of money to activist groups, are often too young to run for office, and cannot yet even cast a vote in some cases, they can exercise their right to protest. And many are. As noted by the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, “Children across the world are taking action, individually and collectively, to protect the environment, including by highlighting the consequences of climate change.”42

But as Mary Lawlor, the Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights Defenders, makes clear in her report from January 17, 2024, young activists face additional obstacles when they seek to make their voices heard.43 Lawlor identified intimidation and harassment in online spaces and the media, lack of adequate support from traditional allies, academic sanctions, and legal, administrative, and practical barriers to participation in civic space as just some of the hurdles faced by child and youth activists. Despite these barriers, she notes, “child and youth human rights defenders have been at the forefront of human rights movements and have achieved a significant impact, which should be acknowledged, celebrated and highlighted.”44

And it is not just the youth who are protesting. People of all ages are using the right to peaceful protest and civil disobedience – a bedrock of a democratic society and the centerpiece of the civil rights and anti-apartheid movements, among many others – as a way to raise awareness about climate change and to press for action by governments and corporations.

Some activists and organizations believe that disruptive protests can play a key role in the fight against climate change by challenging the status quo and amplifying urgent calls for transformative action. By disrupting everyday routines and drawing attention to threats caused by climate change, activists believe they can push the climate crisis to the forefront of public discourse, compelling governments and businesses to reevaluate policies and practices and to finally meet their international obligations to urgently reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Disruptive protests and civil disobedience not only express the collective frustration with the pace of change, but also embody a grassroots demand for swift and substantial measures to mitigate climate change. In doing so, some believe they can contribute to shaping a global consciousness that recognizes the urgency of the climate crisis and underscores the need for immediate, impactful solutions. As German climate protester Christian Bergemann told Climate Rights International:

We try to use these consequences…to highlight the injustice that is happening to people like us who try to be an alarm for this crisis that we’re facing. That their houses are raided and that they are taken into preventative custody, but not the people who have caused this crisis.45

Peaceful protests empower individuals to advocate for change, monitor governments’ climate commitments, and participate in public affairs to drive climate solutions. Through these collective efforts, individuals can rally fellow citizens and press governments to change policies and practices that have caused the climate crisis and promote new policies that would protect people and the planet from the most dangerous consequences of climate change.

By actively engaging with protesters and respecting their right to dissent, democratic countries foster a space that encourages dialogue, understanding, collaboration, and progress. This, in turn, strengthens the democratic fabric by ensuring that diverse voices are heard and can contribute to the development of well-informed policies that address the pressing challenge of climate change faced by society as a whole.

Governments should welcome peaceful protests as the sign of an engaged citizenry. Those who engage in peaceful protest should, at a minimum, be assured that their rights will be respected.

Christian Bergemann at a roadblock protest in Germany. © Last Generation

Key Recommendations

To protect the right of peaceful protest, national and state governments and local authorities should:

- Promote and protect peaceful protest: National, state, and local governments and authorities should actively promote and protect the value and importance of peaceful protest as a cornerstone of democratic participation. Public education campaigns and outreach efforts should be used to help cultivate an understanding of the role that peaceful protest plays in advocating for social change and holding governments and institutions accountable.

- Adopt a proactive approach to facilitating and protecting peaceful demonstrations: Provide guidance, resources, support, and security to protesters to ensure that protests are conducted safely and responsibly.

- Review, repeal, or amend legislation restricting the right to protest to meet international standards: Governments should urgently review legislation that restricts the right to protest to ensure that it complies with international standards for protection of that right, and amend any laws that do not comply with those standards. (For specific recommendations for individual laws, see the full recommendations at the end of this report.)

- Ensure fairness for climate protesters in legal proceedings by allowing a public interest defense and an explanation of motivations: Courts and judges should allow climate protesters to present the motivations for their actions as part of their defense to ensure the right to a fair trial, as guaranteed by international human rights law. Acknowledging the defendants’ intentions and their belief in the imminent threat posed by climate change should be a legitimate factor for courts and juries to consider when making their decisions.

Methodology

This report is informed by a combination of secondary sources and primary research focused on peaceful climate protests and their consequences.

We conducted an extensive review of legal and other responses to climate protests in democratic countries. This involved searching various newspapers, journals, court records, and other articles for information. We also reviewed academic sources, policy documents, and reports from non-governmental organizations.

Our research included over 40 climate protest cases across Australia, France, Germany, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States, each of which was considered under international and domestic standards for the right to protest. To ensure accuracy and comprehensiveness, we consulted with legal experts across various countries.

Primary data collection involved conducting interviews with six climate protesters. These interviews took place between November 16, 2023, and June 12, 2024. Interviewees were asked to share their experiences and perspectives on their climate protests and the subsequent consequences of those actions. All participants provided informed consent to participate, and none received financial incentives.

By combining a thorough survey of the current legal landscape with primary research, this report aims to provide a nuanced understanding of the disproportionate responses that peaceful climate protests are facing, highlighting the experiences of protesters and the legal context within which these protests occur.

CHAPTER 1 – The Right to Protest Under International Law

The rights to freedom of expression, association, and assembly, and the right to participate in public life, are fundamental rights protected under international law. They are inscribed and endorsed across conventions and treaties, most notably the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which has been ratified by 173 countries, including all of the countries referenced in this report.46 They are also found in regional human rights treaties, including the European Convention on Human Rights.47 Children also have the rights to freedom of expression, association, and assembly, as specifically recognized under the Convention on the Rights of the Child. The Committee on the Rights of the Child has made clear that “States shall respect and protect children’s rights to freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly in relation to the environment, including by providing a safe and enabling environment and a legal and institutional framework within which children can effectively exercise their rights.”48

Extinction Rebellion peaceful protestors. Credit: © Maarten Photomic.

Freedom of Assembly

As the U.N. special rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and association, Clement Voule, has stated, “The exercise of the right to peaceful assembly is one of the most important tools people have for advocating for more effective and equitable climate action and environmental protection.”49

Article 21 of the ICCPR guarantees the right of peaceful assembly, stating that no restrictions can be placed be placed on this right “other than those imposed in conformity with the law and which are necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security or public safety, public order (ordre public), the protection of public health or morals or the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.”50 Freedom is the rule, and its restriction the exception.51 The right to freedom of assembly is also protected in Article 11 of the European Convention on Human Rights and under the Constitution, Bill of Rights, or other basic law of all of the countries covered in this report except Australia.52

General Comment 37 of the U.N. Human Rights Committee, the body tasked with interpreting the ICCPR, notes that the scale and nature of peaceful assemblies can cause disruption, such as to vehicular or pedestrian movement. These consequences, whether they are intended or not, “do not call into question the protection such assemblies enjoy.”53 As Voule has stated, “a certain level of disruption of ordinary life, including disruption of traffic, annoyances and inconveniences to which business activities are subjected must be tolerated if the right to freedom of peaceful assembly is not to be deprived of meaning.”54

In General Comment 37, the Human Rights Committee further outlines the positive and negative duties imposed on the State before, during, and after peaceful assemblies. States are obliged to promote an enabling environment for the exercise of the right without discrimination, and to put in place a legal and institutional framework within which the right can be exercised effectively.55 General Comment 37 emphasizes the particular importance of the right to protest where individuals may be in the minority or be expressing dissenting views.

States also have negative obligations not to prohibit, restrict, block, disperse, or disrupt peaceful assemblies absent compelling justification, and not to punish participants or organizers without legitimate cause.56Blanket restrictions on protests are “presumptively disproportionate.”57 While the time, place, and manner of assemblies may under some circumstances be the subject of legitimate restrictions under Article 21, “Given the typically expressive nature of assemblies, participants must as far as possible be enabled to conduct assemblies within sight and sound of their target audience.”58

State obligations to protect the right to protest extend to actions such as participants’ or organizers’ mobilization of resources; planning; dissemination of information about an upcoming event; preparation for and travelling to the event; communication between participants leading up to and during the assembly; broadcasting of or from the assembly; and leaving the assembly afterwards. These activities may, like participation in the assembly itself, be subject to restrictions, but these must be narrowly drawn.59

The comment makes clear that collective civil disobedience or direct-action campaigns are covered by Article 21, provided that they are non-violent.60 As Michel Forst, UN Special Rapporteur on Environmental Defenders under the Aarhus Convention, has explained:

Under international human rights law, civil disobedience is recognized as a form of exercising the rights to freedom of expression and freedom of peaceful assembly, as guaranteed by Articles 19 and 21 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) respectively. Peaceful protest can take many forms and mostly will not amount to “civil disobedience” (since civil disobedience involves an act of deliberate law-breaking). However, all acts of civil disobedience are a form of protest, and, as long as they are non-violent, they are a legitimate exercise of this right.61

Any sanctions, according to General Comment 37, “must be proportionate, non-discriminatory in nature, and must not be based on ambiguous or overbroadly defined offenses, or suppress conduct” protected under the ICCPR.62

Finally, only in exceptional cases may the assembly be dispersed. States can engage in dispersal if the assembly is no longer peaceful or there is clear evidence of an imminent threat of serious violence that cannot be addressed through proportionate measures such as targeted arrests. An assembly that remains peaceful while nevertheless causing a high level of disruption, such as the extended blocking of traffic, may be dispersed, as a rule, only if the disruption is “serious and sustained.”63 The use of force to disperse an assembly should be avoided and, if where that is not possible, only the minimum force necessary may be used. Force that is likely to cause more than negligible injury should not be used against individuals or groups who are passively resisting.64

Freedom of Expression

The right to freedom of expression is provided for in Article 19 of the ICCPR and Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights.65 The right to freedom of expression is not absolute. Given its paramount importance in any democratic society, however, the UN Human Rights Committee has held that any restriction on the exercise of this right must meet a strict three-part test. Such a restriction must (1) be “provided by law”; (2) be imposed for the purpose of safeguarding respect for the rights or reputations of others, or the protection of national security or of public order (ordre public), or of public health or morals; and (3) be necessary to achieve that goal.66

The UN Human Rights Committee, in General Comment 34, made clear that restrictions on free expression should be interpreted narrowly and that the restrictions “may not put in jeopardy the right itself.”67 The government may impose restrictions only if they are prescribed by legislation and meet the standard of being “necessary in a democratic society.” This implies that the limitation must respond to a pressing public need and be oriented along the basic democratic values of pluralism and tolerance. “Necessary” restrictions must also be proportionate, that is, balanced against the specific need for the restriction being put in place. General Comment 34 also provides that “restrictions must not be overbroad.” Rather, to be provided by law, a restriction must be formulated with sufficient precision to enable an individual to regulate his or her conduct accordingly.68

The guarantee of freedom of expression applies to all forms of expression, not only those that fit with majority viewpoints and perspectives. As the European Court of Human Rights held in the seminal Handyside case interpreting article 10 of the ECHR:

Freedom of expression constitutes one of the essential foundations of [a democratic] society, one of the basic conditions for its progress and for the development of every man…. [I]t is applicable not only to ‘information’ or ‘ideas’ that are favourably received or regarded as inoffensive or as a matter of indifference, but also to those that offend, shock or disturb the State or any sector of the population. Such are the demands of pluralism, tolerance and broadmindedness without which there is no ‘democratic society’.69

With respect to criticism of government officials and other public figures, the Human Rights Committee has emphasized that “the value placed by the Covenant upon uninhibited expression is particularly high.”70 Thus, the “mere fact that forms of expression are considered to be insulting to a public figure is not sufficient to justify the imposition of penalties.”71

Freedom of Association

Article 22 of the ICCPR states that everyone shall have the right to freedom of association with others.72 The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights has highlighted that this right “involves the right of individuals to interact and organize among themselves to collectively express, promote, pursue and defend common interests.”73 Freedom of association is vital to ensure the right to peaceful assembly, as it “protects collective action, and restrictions on this right often affect the right of peaceful assembly.”74 The right is also protected under Article 11 of the European Convention on Human Rights.75

The right to form and join an association is an inherent part of the right to freedom of association. As the European Court on Human Rights has stated, “the ability to form a legal entity in order to act collectively in a field of mutual interest is one of the most important aspects of the right to freedom of association, without which that right would be deprived of any meaning.”76 The protections of the right apply equally to associations that are not formally registered with the authorities. Individuals involved in unregistered associations should be free to carry out the same activities as a registered association, including the right to hold and participate in peaceful assemblies.77

Under the ICCPR, no restrictions may be placed on the exercise of this right other than those which are prescribed by law and which are necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security or public safety, public order (ordre public), the protection of public health or morals, or the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.78 The suspension and the involuntarily dissolution of an association are the severest types of restrictions on freedom of association. As a result, this should only be possible when there is a clear and imminent danger resulting in a flagrant violation of national law, in compliance with international human rights law. It should be strictly proportional to the legitimate aim pursued and used only when softer measures would be insufficient.79

The Right to Participate in Public Affairs

The rights to freedom of assembly, freedom of expression, and freedom of association are critical to and inseparable from the right to participate in public affairs. The importance of the right to public participation in the context of climate change is undisputed. As Ian Fry, the first special rapporteur on human rights in the context of climate change, stressed, “the voices of those most affected must be heard” in local, national, and international discussions about climate change.80

This right is protected under Article 25 of the ICCPR, which states that all citizens shall have both the opportunity and the right to take part in the conduct of public affairs, either directly or through freely chosen representatives.81 The right to participate in public affairs includes not only the right to vote and to run for public office but also the right to participate through public debate and dialogue with elected representatives.82 As the UN Human Rights Committee stated in General Comment 25 on the right to participate in public affairs:

Citizens also take part in the conduct of public affairs by exerting influence through public debate and dialogue with their representatives or through their capacity to organize themselves. This participation is supported by ensuring freedom of expression, assembly and association.83

The importance that participation in public affairs plays in protecting the environment was identified as far back as the 1992 Rio Declaration on the Environment and Development, signed by more than 175 countries. It states:

Environmental issues are best handled with the participation of all concerned citizens, at the relevant level. At the national level, each individual shall have appropriate access to information concerning the environment that is held by public authorities, including information on hazardous materials and activities in their communities, and the opportunity to participate in decision-making processes. States shall facilitate and encourage public awareness and participation by making information widely available. Effective access to judicial and administrative proceedings, including redress and remedy, shall be provided.84

The United Kingdom and all of the European countries referenced in this report are also parties to the Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice (“Aarhaus Convention”).85 Each party to the Convention has agreed to “guarantee the rights of access to information, public participation in decision-making, and access to justice in environmental matters in accordance with the provisions of this Convention.”86 As of now, there are 47 parties to the Aarhus Convention, including the European Union as a regional inter-governmental organization.87

Climate activist Luisa Neubauer speaks to activists protesting against an LNG terminal being built off of Rügen in Germany. April 30, 2023. Credit: © Fridays4Future.

CHAPTER 2 – Excessive Government Actions Against Climate Protesters

A number of democratic governments are taking actions that are at best inconsistent with the legally binding standards set forth above, and in some cases represent clear violations. These include imposing disproportionate penalties on peaceful climate protesters and taking preemptive action to prevent protests from occurring instead of creating an enabling environment for peaceful protests.

While protesters who engage in peaceful civil disobedience and intentionally violate laws during those demonstrations may face repercussions for those violations, any sanctions must be proportionate to the harm caused. Disproportionate responses from the police, prosecutors, or judges aimed at deterring others from exercising their right to protest are inconsistent with international law.

Disproportionate Penalties for Disruptive Protests

In the United Kingdom, Stephen Gingell is believed to be the first person jailed under the controversial new UK law that bans interference with key national infrastructure.88 A Just Stop Oil supporter, Gingell was one of roughly forty individuals who spent half an hour on November 12, 2023, marching on Holloway Road in North London to protest the United Kingdom’s failure to adequately address climate change.

The police log detailing Gingell’s action notes that the protesters were given orders to disperse, but that the demonstrators continued to slow march until they were arrested.89 Nothing in the log describes any other inciting action. Gingell pled guilty to breaching section seven of the Public Order Act 2023. On December 15, 2023, he was given a six-month prison sentence for his thirty minutes of peaceful protest.

In 2022, Gingell had shared his motivations for engaging in Just Stop Oil protests, stating, “I’ve got no choice. I’ve got three lovely children – what future are they going to have? I really fear for their lives.”90

Gingell was one of 630 climate protesters arrested in the UK in November 2023.91 At least 125 were charged, as was Gingell, with blocking key national infrastructure in violation of section 7 of the Public Order Act 2023. Some of those arrested for slow marching were remanded for up to 30 days.92 On November 20, 2023, 15 activists were arrested after just two minutes of marching.93

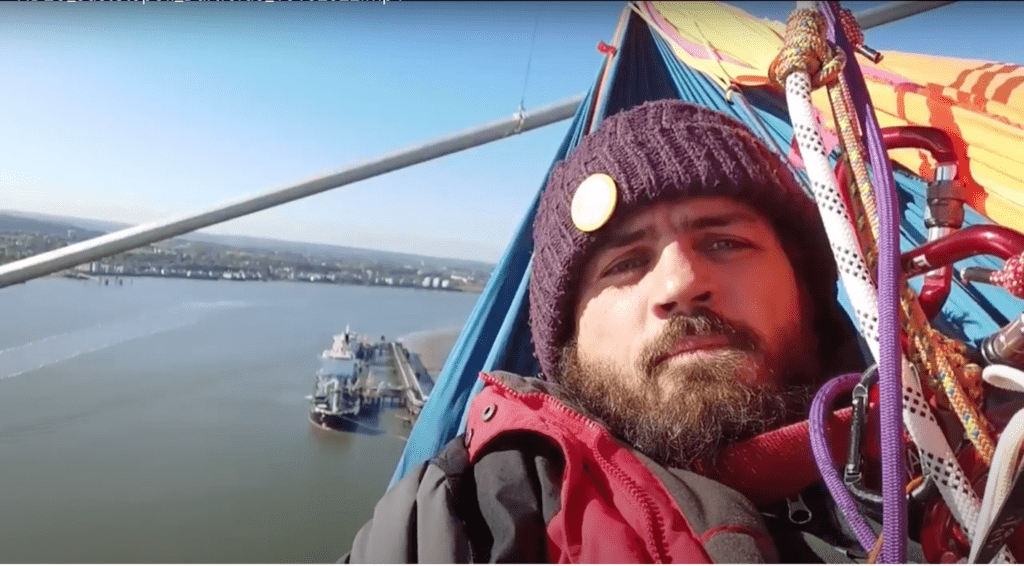

The crackdown on peaceful climate protesters in the UK has been underway for several years. On October 17, 2022, Morgan Trowland and Marcus Decker climbed the Queen Elizabeth II Bridge in London and remained there for 36 hours.94 Supporters of Just Stop Oil, the purpose of their protest was to call for the UK government to stop licensing all new oil, gas, and coal projects.95 On October 18, 2022, Decker and Trowland were arrested, and ultimately charged, under section 78(1) of the overly broad and vague 2022 Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act, with intentionally causing a public nuisance.96 On April 21, 2023, Decker was convicted and sentenced to two years and seven months in prison.97 On the same day, Trowland was also convicted of causing a public nuisance and received a three-year sentence, reportedly the longest ever for a peaceful climate protest in the United Kingdom – equating to a month in prison for every hour he was on the QEII Bridge.98

Making explicit his intent to discourage similar protests, Judge Collery KC, the presiding judge, stated that the severity of the punishment was intended, in part, “to deter others from copying you.”99 Prime Minister Rishi Sunak defended the severe sentences, stating, “It’s entirely right that selfish protesters intent on causing misery to the hard-working majority face tough sentences. It’s what the public expects and it’s what we’ve delivered.”100

Following his release from prison on December 12, 2023, Trowland stated, “You have to demonstrate via actions that this is really serious and more important than our individual lives. I had an opportunity to demonstrate that as best I could, and I couldn’t look back and live with myself knowing I had that opportunity and turned it down.”101

Morgan Trowland atop the Queen Elizabeth II Bridge in London. October 17, 2022. © Just Stop Oil

While Decker, a German citizen residing in the UK with his partner and children, was serving his prison sentence, he was served a deportation order by the UK government.102 He has filed a legal challenge to that order. In the meantime, more than 150,000 people have signed a petition opposing his deportation,103 while a group of leading actors and musicians have called on the UK government to reconsider, noting that punishing Decker with deportation “in addition to the 14 months he has already spent in prison is out of proportion to the crime committed and unconducive to the public good.”104

Decker was released on bail on February 19, 2024, having been imprisoned for 490 days for his peaceful demonstration. Upon his release, Decker stated, “With tipping points in the climate system dangerously close and complete societal breakdown therefore on the horizon during my lifetime, it’s obvious that many more people will be taking action as our situation worsens.”105

The penalties continue to escalate. Judge Christopher Hehir stated that the Decker and Trowland sentences were a new reference point for the July 18, 2024 sentencing of five members of Just Stop Oil. Roger Hallam, Daniel Shaw, Louise Lancaster, Lucia Whittaker De Abreu, and Cressida Gethin were found guilty of conspiring to cause a public nuisance for their alleged role in the planning of the protests in the November 2022 protests on the M25 in London. 106 The protest lasted four days. Shaw, Lancaster, Whittaker De Abreu, and Gethin received sentences of four years. Hallam received a sentence of five years, believed to be the longest ever given in the United Kingdom for a non-violent protest.107 Like Decker and Trowland, they were also convicted under section 78 of the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act of 2022. 108

At the heart of the case was a Zoom call in which all five protesters were present.109 Judge Hehrir said the Zoom call, which was recorded by an infiltrating journalist from the “Sun” tabloid, revealed, “intricate planning and the level of sophistication involved” in the demonstration on the M25.110 Hallam argued that he was not involved in the action, instead having just been asked to speak on the Zoom call. 111 Following his sentence, Hallam wrote on X:

I’ve just been sentenced to the 5 years in prison. The longest ever for nonviolent action. The ‘crime’? Giving a talk on civil disobedience as an effective, evidence-based method for stopping the elite from putting enough carbon in the atmosphere to send us to extinction. I have given hundreds of similar speeches encouraging nonviolent action and have never been arrested for it. This time I was an advisor to the M25 motorway disruption, recommending the action to go ahead to wake up the British public to societal collapse. I was not part of the planning or action itself.112

The trial itself lasted over two weeks. Police were called to the court at least seven times; four of the defendants were remanded to prison for defying the judge and explaining that climate change was the motivation for their actions.113

The sentences were longer than those imposed on some of those involved in violent riots in the UK following the stabbing of several young girls in Southport.114For example, the longest sentence imposed on three men who admitted participating in violent disorder and, according to Assistant Chief Constable Paul White of the Merseyside Police, “were part of a group who brought violence to the streets of Southport, causing harm and fear in a community that was already in shock,”115 was two years and six months – exactly half as long as Roger Hallam received. 116

The UK is not the only democratic country in which climate protesters are being given disproportionate sentences. The day before the five protesters were sentenced in the United Kingdom, Germany sentencedMiriam Meyer to sixteen months in prison without parole, at the time the highest sentence ever imposed in Berlin against a peaceful climate activist.117 During the proceedings, Meyer shared that she wanted to continue taking part in protests. The court cited this as a reason for the sentence because it viewed the response as Meyer having shown no remorse for her actions. 118As an activist and member of Letzte Generation, Meyer had engaged in gluing herself to roads several times as well as being involved in painting the face of the Federal Ministry of Transport building.119To remove the orange point required a cost of roughly €7,400.120 She was found guilty of property damage, resistance to law enforcement officers, and coercion.121The verdict is not final.122

And just over a month later, a new record was set. On August 27, 2024, 65-year-old Winfried Lorenz received nearly two years in prison for a roadblock climate protest. 123The 22-month sentence for the action was a dramatic change from a previous roadblock case against Lorenz, at which the presiding judge found that the road blocks had not exceeded “the socially acceptable levels” and acquitted Lorenz and his co-defendants.124Lorenz’ attorney criticized the sentence, stating, “Such a high sentence for someone without a criminal record and who has done nothing other than taking part in a sitting blockade and refusing a deal offered by the judge has nothing to do with implementation of the penal code.125 Lorenz plans to appeal the court’s decision and the verdict is not yet final.126

In Australia, Deanna “Violet” Coco became one of the first individuals to be sentenced under one of Australia’s new anti-protest laws, which allow for more severe penalties for demonstrations involving “vital infrastructure.”127 On April 13, 2022, Coco blocked one lane of traffic on the Sydney Harbour Bridge for a total of 28 minutes to call on the Australian government to take greater action on climate change.128 The Sydney Harbour Bridge has a total of five lanes. Following her arrest, Coco pled guilty to breaching traffic laws, to lighting a flare, and to disobeying police orders to move on — all of which are non-violent offenses. Despite the short duration, the limited scope, and the peaceful nature of the demonstration, Coco was sentenced to 15 months in prison on December 2, 2022.129

Additionally, Coco was initially denied bail pending the appeal of her sentence, something that her counsel, Mark Davis, noted was unusual for a non-violent offender. “You’ve normally got to be a pretty monstrous person to be denied,” Davis said.130 Ten days later, following a bail appeal and with more than 100 protesters gathered outside the court, Coco was released on AU$10,000 bail but was ordered by the magistrate not to leave her apartment unless there was a medical emergency or if she was going to court.131 This stipulation lasted for three weeks until it was amended to allow her to leave between 10 a.m. and 3 p.m. On March 14, 2023, the 15-month sentence was quashed on appeal, with the judge noting that similar matters in the past had been dealt with through fines or bonds without convictions.132

The premier of New South Wales, Dominic Perrottet, backed the original harsh sentence by stating, “If protesters want to put our way of life at risk, then they should have the book throw at them and that’s pleasing to see.”133

When government officials denounce peaceful protesters with demeaning language it not only undermines the fundamental right to protest but also sends a chilling message to others who may consider engaging in peaceful protest.

These decisions in the UK and Australia stand in stark contrast to a recent case in The Netherlands.134 There, two Belgian protesters glued themselves to the painting “The Girl with the Pearl Earring,” as a form of protest against climate change. The judge in that case reportedly gave the men shorter sentences than those sought by prosecutors because, she said, she did not want to discourage future protests.135 The Hague Court of Appeal went a step further, overturning the sentences on the ground that any prison sentence, even the shortened one imposed by the trial court, would risk infringing on protected freedoms.136 In a statement to the media, a court spokesperson said that court did not want to discourage others who wish to peacefully protest or exercise their right to freedom of expression, noting that a disproportionate punishment of these protesters might have a “chilling effect” on others.137

Some governments have employed double standards towards protesters, with the response varying depending on the cause they are advocating. The glaring discrepancy between the harsh treatment of peaceful but disruptive protest in support of increased action on climate change and similarly disruptive protests in pursuit of certain other goals was exemplified by the governmental response to farmers protestingthe European Union’s Green Deal and climate policies in the beginning of 2024.138 Protests by farmers included extended road blockades with tractors and heavy machinery, destruction of property, burning of tires, the toppling of a statue in front of the European Parliament, and violent confrontations with law enforcement.139Despite such violent and often dangerous actions, protesting farmers were not demonized. Instead, EU officials and member states’ governments negotiated with farmers, offering concessions in relation to EU climate targets and agricultural emission cuts.140The disparate treatment of those protesting different issues is in clear violation of the obligation of governments to be content neutral in the way they approach peaceful assemblies and in any restrictions they impose on assemblies.141

Moving from Europe to the United States, another case of excessive sentencing of a climate protester occurred when Jessica Reznicek, a veteran climate activist in the United States, used fire and chemicals to destroy equipment that was being used in the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline in 2016.142 No one was injured.143 Reznicek considered her action to be a nonviolent act of civil disobedience intended to help protect the planet, and she pled guilty to conspiracy to damage an energy facility, expecting to be sentenced to two to four years in prison, according to her attorney.144 However, the U.S. Justice Department asked the judge to apply a sentencing increase known as the “terrorism enhancement,” which significantly increases possible sentences for cases involving domestic terrorism.145 The trial judge agreed, stating that she found Reznicek’s actions were, “calculated to influence or affect the conduct of government.”146 Reznicek was sentenced to eight years in prison in 2021.147

On appeal, Reznicek argued against the reasoning applied by the judge, noting that her demonstration was aimed at a private company and thus not against the government of the United States. The decision and lengthy sentence were upheld by the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in 2022.148 The Court found that “any error was harmless” because Judge Ebinger stated on the record that she would have given an eight-year sentence without the terrorism enhancement. The case is an extreme example of the treatment of climate activists as “terrorists” and “extremists” by democratic governments.149 Most climate protests, and protests in general, are “calculated to influence government action” – it is part of the critical role that the right to protest plays in a democracy. Treating a protest as “terrorism” because of the motivation behind it is a fundamental assault on the right to protest.

UN Special Rapporteur Michel Forst has highlighted the increasing conflation of terrorism and climate activism by both political figures and in legislation and policy papers. For example, the 2023 European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend report features climate activism in its entries on “extremism” and appears to take the view that worrying about climate change is an extremist viewpoint, stating: “Environmental extremists are concerned with various themes, such as climate change and earth resources.”150

Disproportionate Penalties for Symbolic Protests

Symbolic protests often involve engaging in action at a location that is not immediately synonymous with contributing to climate change. Instead, activists choose a venue to host their protest that they hope will resonate with others or amplify their message. By staging protests at museums, some activists believe they can strategically draw attention to the interconnectedness of environmental issues and cultural preservation, emphasizing the threat climate change poses to both natural ecosystems and human history. Some activists believe such protests prompt reflection on the environmental impact of human activities and compel individuals and institutions alike to reevaluate their roles in addressing the climate crisis, fostering a broader societal commitment to sustainable practices.

Timothy Martin and Joanna Smith believe that museums hold unique significance in the fight against climate change. They told Climate Rights International that museums are institutions that safeguard our history. They believe museums act as cultural institutions and often serve as symbolic representations of societal values and heritage. For this reason, they chose to stage a protest at the National Gallery in Washington D.C.151 On April 27, 2023, they entered the museum with red and black water-soluble paint, put some on their hands, and then swiped across the protective case housing “The Little Dancer,” a sculpture by Edgar Degas. When asked why they chose this piece as their vehicle, Martin told Climate Rights International, “It was kind of an obvious choice, right? It’s a child and she’s in a kind of vulnerable position.”152

Martin and Smith said that the purpose of their protest was to encourage U.S. leaders to take serious action in the fight against climate change.153 As Smith told Climate Rights International, her actions were designed to symbolize her rejection of the United States’ inaction in the unfolding climate crisis:

We don’t consent to this. We do not consent. And so, this is the consequence of not consenting, I guess. But it shouldn’t be. You should be able to not consent in a peaceful way [without being charged with a felony].154

Climate protests involving works of art have also taken place in Germany,155 the United Kingdom,156 and Spain,157 among other countries. Most of these protests have been designed to avoid damage to the art itself and have resulted in charges of trespassing or causing damage to public work penalized by a modest fine and sometimes restitution. That was the precedent that Martin and Smith expected when they undertook their actions. But the treatment they received was far harsher than expected.

Smith told Climate Rights International that after they smeared the paint on the protective case, they sat in a position of surrender with their hands up. But once security from the museum collected them, Smith, who has a pre-existing health condition that affects her connective tissue, said that she was handcuffed in a way that exacerbated the condition in her shoulders and elbows. “I was left like that for several hours until I was crying in pain,” Smith said. Only then was she uncuffed.158

The authorities charged Martin and Smith with conspiracy to commit an offense against the United States and injury to a National Gallery of Art exhibit – felony offenses that carry penalties of up to five years in prison and a fine of up to $250,000. Conspiracy to commit an offense against the United States is a charge that can be brought when two or more people plan to damage U.S. property or interests in some way.159 Something of a catch-all charge, it has been brought against Volkswagen AG executives for trying to cheat emissions tests, chief executives of energy company Enron, and Donald Trump’s former campaign manager Paul Manafort for failure to report overseas financial holdings.160

While their cases were pending, they faced serious restrictions on their lives and activities. They were required to turn in their passports and check in with authorities on a weekly basis and were forbidden from setting foot in any museum. Smith told Climate Rights International that the risk of severe consequences has chilled her ability to exercise her first amendment rights. She stated that since she found out about the federal charges, she hasn’t felt comfortable engaging in protests in her home of New York City. “I can’t be physically present where I want to be present,” she said.161

Despite everything, Martin and Smith feel their actions were necessary due to the existential threat of the climate crisis. “We tried. We can look our kids in the eyes and say we did everything we can,” Martin said.162

On December 15, 2023, Joanna Smith pled guilty to one count of causing injury to a National Gallery of Art exhibit.163 On April 26, 2024, a day shy of one year since her protest, Smith received 60 days of prison time.164 Additionally, Judge Amy Berman Jackson sentenced Smith to serve 24 months of supervised release as well as 150 hours of community service. Ten of those hours must involve cleaning graffiti. Furthermore, Smith must pay a court fee, a $3,000 fine, and restitution to the Degas exhibit totaling $4,062. Finally, Smith is barred from entering Washington D.C. as well as being barred from all museums and monuments for two years.165 Martin’s trial is scheduled for August 26, 2024.166

Harsh penalties are even being sought for satirical forms of protest. In New Zealand in 2019, climate activist Rosemary Penwarden drafted a satirical letter masquerading as a fossil fuel conference organizer, claiming that the conference was cancelled.167 The letter concluded with the line, “But there is a silver lining to all of this: we will not be there to listen to that incessant chanting,” a punchline that winked at the chanting of protesters at previous fossil fuel events.168

The actual organizers received word about Penwarden’s letter and reassured attendees that the event was still on, and the conference was held without issue.169 Penwarden herself admitted that the letter’s chief aim was to “ruffle feathers” rather than attempt to stop the conference.170 Yet the authorities charged Penwarden with forgery, a felony carrying a penalty of up to 10 years of prison. In 2020, Penwarden was arrested by the police, who confiscated her laptop and cell phone. Despite satire having a longstanding history of being used in protest movements, New Zealand prosecutors claimed Penwarden’s act was a way “to cause disruption to the conference with a thinly veiled defence of satire woven into it.”171

In October 2023, Penwarden was found guilty of forgery and sentenced to 125 hours of community work.172

Preemptive Arrests

Some national and state governments are taking action to prevent protests before they even occur, whether by taking protesters into preventative detention, arresting those encouraging attendance at protests, issuing blanket bans on protests, or taking legal action to try to disband climate advocacy groups. These preemptive measures, while purportedly aimed at maintaining public order, pose significant risks and challenges to fundamental human rights.

In January 2023 Sieger Sloot, a Dutch actor and climate activist, encouraged his followers on X, formerly Twitter, to join an upcoming Extinction Rebellion demonstration.173 Two days before the protest occurred, police officers arrived at Sloot’s home to arrest him. Sloot, who was not home at the time, told Climate Rights International that the police came to his house at 7:00 a.m., banging on the door and frightening his two young children, who were home with his wife. Sloot said:

I had to explain to my children. I had told them the police are here to help us. And now I had to explain to them, “They think I’m a crook, I am not a crook.” I know what I did. I’m totally behind what I did.174

Sloot was arrested and charged with the felony of sedition, defined in the Netherlands as “inciting others” to commit a criminal offense.175 In August 2023 he was convicted and sentenced to 60 hours of community service or 30 days in jail.176 His sentence is under appeal in a higher court.177

The use of sedition charges against those calling for climate protests – a form of non-violent civil disobedience – is a disproportionate response that will surely have a chilling effect on others. Criminalizing the act of calling for others to participate in such demonstrations violates states’ obligations to protect the right to protest.

Sloot told Climate Rights International that he was shocked at the sedition charge.

For me, I personally draw the line at committing crimes. I wouldn’t have wanted to commit a crime. When joining an action, minor violations, that’s okay with me. I draw the line when it’s real crime. Sedition is a real crime.”178

Sloot was not the only one; six other activists were also convicted of sedition for the same action.179

Sloot has pointed to his heightened “climate anxiety” as the reason he joined Extinction Rebellion.180 He voiced his frustration at being categorized as a criminal:

We’re not drug lords. We’re just worried citizens who make use of their right to protest, which is fundamental.181

Sieger Sloot and 400 demonstrators protest at Tata Steel in the Netherlands. June 24, 2023. Credit: Sieger Sloot, Instagram

Other climate activists have been held in preventative detention to keep them from attending protests. For example, on June 12, 2023, Simon Lachner was detained by the police in the Bavarian city of Regensburg, Germany because he had planned to join the blocking of a thoroughfare to call attention to climate change.182 Officers waited for him to leave his home, and then placed him in police custody. In the German state of Bavaria, this is possible through a controversial law that allows police to take a person into preventative custody if it is “essential to prevent the imminent commission or continuation of an administrative offense of significant public importance or a criminal offense.”183 The protest went ahead without Lachner, who remained in custody for six hours.184

Sometimes preventative detention can last for days. Climate Rights International spoke with Christian Bergemann, a member of the German climate group Last Generation, who was held for ten days in September 2023 using the same Bavarian law.185 Bergemann stated that the group was planning action in Bavaria, which was hosting an automobile trade fair. He said that Last Generation was aware that several cases of preventative detention had previously occurred in Bavaria. The group blocked roads to protest the trade fair, and Bergemann was detained by police and transferred to the Munich police station, where he then met with a judge. “The judge asked, ‘Are you going to keep doing street protests in the next days in the form that you have been previously?’ And I said, ‘That’s what I’m planning on doing because we’re in the middle of a crisis that’s going to cost us everything,’” Bergemann said. The judge told him he understood his motives but did not approve of the means and ordered that he be detained for 10 days.186

Bergemann told Climate Rights International that, while he was aware he might end up in preventative custody, the experience still had unexpected impacts. “The situation that we are in as a society, as mankind, that they find it adequate to bring someone into jail because they protested against this obvious lack of action. That was something that shocked me when getting in there as well.” Bergemann stated that the actual 10 days in jail was manageable because he was not alone. There were 40 Last Generation protesters who had been similarly detained, some for as many as 30 days.

As for the lasting impacts, Bergemann said:

It somehow changed my way of thinking about our democracy, about our police, about our courts. Before, I thought actually courts usually took reasonable decisions and you couldn’t just request anything as the police in front of a judge. Which looking back was a bit naïve. It’s somehow easier than you think and the connections between the different powers in our State are pretty tight.187

These preventative detentions for planned climate protests, even with the caveat that there must be an imminent criminal offense to be prevented, violate fundamental rights to freedom of assembly, expression, and association. By preemptively detaining individuals before they engage in protest activities, authorities not only violate the right of those individuals to engage in peaceful protest, but also send a chilling message that dissent and activism will be met with punitive measures, thereby deterring others from exercising their fundamental rights to assembly and free speech. This chilling effect not only stifles the expression of dissent but also undermines the democratic process itself, as it diminishes citizens’ capacity to hold their governments accountable for environmental policies and actions.

Blanket Bans on Protests

Some governments have issued blanket bans on certain forms of protests, despite the fact that blanket restrictions on protests are “presumptively disproportionate.”188 After activists engaged in a series of airportblockades in Berlin and Munich calling for an end to artificially cheap air travel and advocating for more train options, the German government issued a 30 day blanket ban on all climate-related gatherings aimed at blocking key roads and other areas in Munich.189

On October 14, 2019, British police ordered Extinction Rebellion activists to cease climate demonstrations throughout London entirely or face arrest.190 The climate action, billed as “Autumn Uprising,” had been underway for nine days and was scheduled to last two weeks. In just over a week, the demonstrations saw the arrest of more than 1,400 protesters. The Metropolitan Police stated that, after nine days of disruption, they felt it was proportional to impose the city-wide ban due to “the cumulative impact of these protests.”191

The ban was issued under Section 14 of the UK’s Public Order Act.192 Howard Rees, an Extinction Rebellion spokesman, stated that officers headed for Trafalgar Square before the revised order was even issued. Police had previously been telling protesters to go to Trafalgar Square if they wished to continue to engage in their demonstrations.193

Kevin Blowe, coordinator for the Network of Police Monitoring, noted that the order effectively amounted to a ban without the due process that would usually be required to achieve such a ban. Blowe stated, “Our reading of it is that the section 14 powers are supposed to be used with caution because people still have a right to protest and potentially this is unlawful, and there is no other way to put it.”194 The following month, London’s high court found that the ban was unlawful.195

Pushbacks on Climate Advocacy Groups

Authorities in several countries have also taken action against climate change advocacy groups. Members of Last Generation have been subject to criminal investigations in Germany into possible charges of “forming or supporting a criminal organization.”196 On May 24, 2023, the police raided members’ homes in a coordinated operation that spanned seven German states.197 The 170 officers searched homes, seized belongings, and two bank accounts were seized as well as an asset freeze ordered. The members were accused of “organizing a donations campaign to finance further criminal acts” by Last Generation. The authorities stated that the campaign through the group’s website had raised 1.4 million euros.198 The police gave a directive to shut down Last Generation’s website.199

And that was not the end of the saga for the group. On May 23, 2024, a day shy of one year after the raids, five members of Last Generation were charged with “forming a criminal organization” in violation of section 129 of the German criminal code by prosecutors in the town of Neuruppin.200 Prosecutors cited over a dozen actions against oil refineries, airports, and museums as the reasoning behind the charges. Mirjam Herrmann, one of the activists charged, stated, “This is the first time in German history that a climate protest group that uses measures of peaceful civil disobedience is charged as a criminal organization.”201 In a press release, lawyers for the defendants stated: “Here, an attempt is being made to criminalize and thus silence the messenger of the scientifically based message, namely that there are only a few years left in the climate catastrophe to become climate neutral if people want to continue living on Earth in the future,” adding “This will be a long process. We are in the right and we will fight for this right.”202

In 2023, the French government attempted to ban an entire climate activist group. Les Soulèvements de la Terre (Earth Uprisings) had engaged in grassroots campaigns and repeated protests to voice their opposition to new road projects, reliance on nonrenewable resources, and the creation of mega water basins in western France.203 At one demonstration, police fired tear gas and some protesters threw fireworks and other projectiles, leading to injuries on both sides.204 In June 2023, following police intervention in a number of Les Soulèvement de la Terre protests, the French government ordered the dissolution of the organization.205 The government attempted to justify its action by claiming the group provoked violence during some of the protests.206

The backlash against this decision was swift from rights groups and advocates across the globe.207 The organization’s attorney, Raphael Kempf, stated, “It’s an infringement on freedom of expression, it targets speech and not actions.”208 The French group La Ligue des Droits de l’Homme (the Human Rights League) noted that the decision signaled an alarming crackdown on environmental protests more broadly and was intended to silence groups and their supporters. Les Soulevement de la Terre, which has 110,000 registered members, appealed the dissolution and continued protesting.209

In August 2023, France’s Council of State Court suspended the decision, ruling that the disbanding order against the group would restrict activists’ freedom of assembly and that the government had failed to provide sufficient evidence that the organization was inciting violence during their demonstrations.210 France’s top administrative court overturned the ban on the group in November 2023.211 “The dissolution of SLT did not constitute an appropriate, necessary and proportionate measure to the seriousness of the disturbances likely to be caused to public order,” the court said in a statement.212

Extinction Rebellion protestors being sprayed with water. Credit: © Maarten Photomic

Excessive Police Response

In September 2023, more than 10,000 climate activists gathered near The Hague in the Netherlands for an event organized by Extinction Rebellion.213 The protest was in response to a report that showed the Netherlands was spending more than $40 billion per year in subsidies for fossil fuels.214 People from around the country gathered to voice their opposition to this practice, chanting, “The seas are rising and so are we.”215 The protest was made up of individuals of all ages, including young children and the elderly. The activists stated they would stay until the subsidies ended and they would come back every day if necessary.

After several hours and warnings to not block the road, the police began to engage in the use of water cannons. Ultimately, 2,400 protesters were detained, with some reportedly being dragged by police, and placed in orange transports.216 Some of those detained were minors.217

Police in The Hague also used water cannons in May 2023, when 7,000 protesters blocked a section of a roadway outside the city.218 During that protest, 1,579 people were arrested, with 47 ultimately being prosecuted on the following charges: 11 prosecuted on charges of vandalism, 33 prosecuted on charges of blocking and obstructing, two prosecuted on charges of obstruction and insult, and one person prosecuted for resisting arrest.219 Police stated that they had repeatedly given the activists opportunities to cease protesting and disperse before resorting to using the water cannons and making arrests, but Extinction Rebellion claimsthat the water cannons were used just fifteen minutes after the blockade began.220 For all others arrested, the Public Prosecution Service announced that there would be no added value in criminal prosecution because the main purpose of the arrests was simply to end the blockade.221

In Germany, alarm surrounding the use of “pain grips” by law enforcement against peaceful climate protesters has grown. “Pain grips,” also known as pain compliance holds, are techniques that use physical impact to cause pain in particularly sensitive parts of the body.222 On April 20, 2023, the use of a pain grip against peaceful climate protester Lars Ritter was captured on video. In the video,223 Ritter is seated on the ground in the middle of a roadway, while one officer ordered him to move, reportedly stating, “If I inflict pain on you, if you force me to, you will have pain chewing and swallowing for the next few days – not only today.”224 A second officer approached and the two grabbed Ritter, one by the jaw and the other twisted his arm. Ritter then screams in pain on the ground. While some have been concerned by the actions of the police, Berlin Interior Minister Iris Spranger stated in an interview that it was “unfortunate” that car drivers were unable to use violence against protesters.225

Excessive police responses have occurred in the United States as well. The organization Seven Circles Alliance chose to engage in a climate protest at the Burning Man Festival in Nevada on August 27, 2023. They set up a blockade and held signs stating, “Mother Earth needs our help.”226 They were demanding that Burning Man ban single-use plastics and private jets.227 The group blocked the sole route in and out of the festival for thirty-six minutes before officers from the Pyramid Lake Paiute tribal police department arrived.228

According to the protesters, one officer told the protesters that they must disband in 30 seconds or they risked being arrested. A second officer then arrived, his vehicle hitting the trailer used as a blockade, just missing the activists that were chained to it. According to the protesters, they told the officer that they were non-violent, carried no weapons, and were there to demonstrate for the environment.229 Video from the scene appears to show the officer pulling out a firearm, aiming at the activists, and threatening to shoot protesters. He then approached a woman as she lowered herself, grabbing her by the arm, pulling her down, and kneeling on her back. Ultimately, officers cited five of the protesters, but the tribe’s chairman did not state on what grounds.230

Targeting of Journalists and Neutral Observers

In addition to actions against peaceful protesters, law enforcement has also targeted neutral observers, in violation of international standards. The UN Human Rights Committee has recognized the important role neutral observers such as journalists, lawyers, and human rights defenders, can play in protecting the right to peaceful assembly. According to the committee, journalists and neutral observers “may not be prohibited from, or unduly limited in, monitoring and reporting on assemblies, including with respect to monitoring the actions of law enforcement officials. They must not face reprisals or other harassment, and their equipment must not be confiscated or damaged. Even if an assembly is declared unlawful or is dispersed, that does not terminate the right to monitor.”231

In a case in the United Kingdom, police arrested and detained journalists who were covering a climate protest.232 In November 2022, members of the Hertfordshire police force arrested radio reporter Charlotte Lynch, journalist Ben Cawthra, filmmaker Rich Felgate, and photographer Tom Bowles. Bowles and Felgate were arrested on suspicion of conspiracy to cause public nuisance.233 Felgate was detained for 13 hours despite offering to show his press card. He was ultimately released with no further action.234

An investigation into the incident commissioned by the Hertfordshire force initially came to the conclusion that “police powers were not used appropriately,” but they did not reach a determination that the actions of the officers were unlawful.235 However, following legal action by Cawthra, the Hertfordshire constabulary admitted that the officers acted unlawfully in arresting him and violated his rights to free speech, and the force has accepted fault for false imprisonment over his detention.236

On August 22, 2022, Swedish journalist Markus Jordö was detained by Stockholm police while he was documenting a climate protest on a highway for a Swedish public broadcast.237 Jordö says he was not told the reason for his arrest and he did not have an opportunity to identify himself as a journalist, though he felt it was clear he was on a mission for the Swedish public broadcast. 238 They seized his phone and his equipment and he was then brought to a cell where he was strip searched before being interrogated.239.[1] Jordö was detained for eight or nine hours, and charged with sabotage. 240 The charges were dropped later in the week. 241

Just two months earlier, on June 3, 2022, Jonas Gratzer and Noa Söderberg were prevented from covering a protest at the Stockholm +50 climate conference. 242 The media director of the Swedish police later noted that police are aware of the laws on the protection of journalists and expressed regret for the situation. 243

On November 26, 2023, more than 100 climate protesters were arrested in Newcastle, Australia by New South Wales police.244 The protest was organized by Rising Tide, which sought to maintain a 30-hour blockage of the Port of Newcastle via activists in kayaks, aiming to stop coal exports from leaving Newcastle. Rising Tide hoped this would be the largest act of civil disobedience in the history of Australia.

Rising Tide had a permit to protest for 30 hours, but many activists remained in their kayaks beyond the 30 hours, expecting to be arrested.245 109 individuals were detained, and among the group were five minors, one as young as 15.246 Alan Stuart, a 97-year-old minister, was also arrested. He stated, “I am doing this for my grandchildren and future generations because I don’t want to leave them a world full of increasingly severe and frequent climate disasters.”247

Five representatives of Legal Observers NSW, a police watchdog group, were arrested despite being marked in colored vests and repeatedly communicating with police throughout the event.248 Three of the legal observers, and more than 100 protesters, were charged with unreasonable interference with a vessel under the Marine Safety Act, an offense that carries a potential fine of up to AU$5,500. Legal Observers NSW viewed this as an attack on “the right to document and monitor protest as media and independent observers.”249

99 of the protesters arrested and charged were scheduled for court on January 11, 2024 in Newcastle Local Court.250 Magistrate Stephen Olischlager stated that many of the activists had genuine concern for their environment and noted that the protest was “not selfishly motivated.” Those who pleaded guilty did not receive a conviction or a fine, with Magistrate Olischlager stating, “It is a strength of those characters, which on this occasion [means] these are matters that can be dealt with by not proceeding to conviction.”251 Even with the vast number of detentions and charges, Magistrate Olischlager recognized that peaceful protests are a viable way for concerned citizens to raise concerns about the future of the planet.

CHAPTER 3 – New Laws Restricting the Right to Protest

Many of the arrests and prosecutions described above have utilized laws enacted in recent years curtailing the right to protest, particularly in response to climate action. While some governments have attempted to justify such measures as necessary for maintaining order or safeguarding economic interests, the laws, as well as their implementation, are frequently inconsistent with governments’ legally binding international obligations to protect the right to peaceful protest.

As the impact of climate change intensifies and continues to threaten the human rights of present and future generations globally, it is vital for established democracies to foster an environment where members of the public can express concern, mobilize for change, and hold both governments and corporations accountable for actions and shortcomings. Yet many democratic countries, despite their international obligations and their stated commitments to transparency and public participation, are imposing ever greater restrictions on the rights of those seeking to challenge their failure to act on climate change.

The laws discussed below, as well as numerous laws passed but not yet in force and laws that have been proposed, underscore a disturbing trend of some governments prioritizing the convenience of road users and businesses over addressing the urgent environmental issues at hand.

United Kingdom