Many biomedical researchers and physicians hail personalized medicine as a radical, new approach to healthcare. In contrast to the traditional, one-size-fits-all model that treats all patients as if they’re identical, advocates describe personalized medicine as using genetic differences between people to deliver “the right treatment, to the right patient, at the right time.” And rather than just managing symptoms, personalized medicine proponents emphasize how it leverages insights from genetic research to intervene on the biological causes of disease.

The most exciting and ambitious promise of personalized medicine, though, is what it can do to address unjust racial health inequities. African Americans, for example, have frighteningly high rates of cardiovascular disease as well as infant and maternal mortality. Latino Americans more often suffer from obesity and asthma. Indigenous communities in the United States bear an increased burden of diabetes and chronic liver disease.

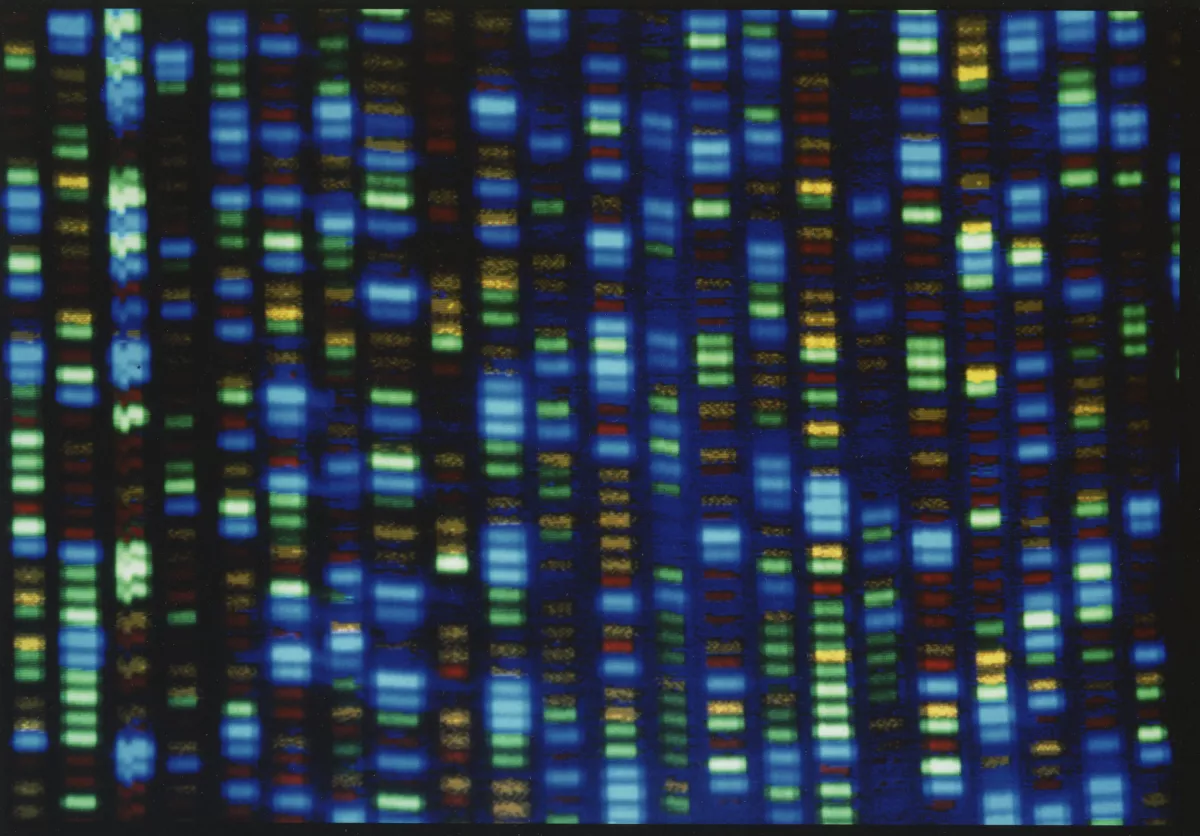

For champions of personalized medicine, gathering genomic information from communities of color is said to be an essential step toward combating the health crises. And, indeed, geneticists have been working hard to make inroads, recruiting people of color to participate in research and contribute their diverse DNA to the fight against health inequality.

It would be natural to applaud this well-meaning effort at making the world a more equitable place. Reflecting on an episode from the history of biomedical research, however, should leave us profoundly worried. Genetic endeavors undertaken with even the best of intentions can miss their mark and, in the process, distract from the actual causes of health disparities, with harmful consequences.

In 1963, federal scientists descended on the Gila River Indian Community outside Phoenix and found something truly shocking. The Akimel O’odham who lived there had Type 2 diabetes at 10 times the rate of the national average at that time. Diabetes results from excess glucose building up in the body, which then wreaks havoc — heart disease, kidney failure, nerve damage. The epidemic was devastating the Indigenous community.

The scientists, intrigued by the severity of the problem and genuinely interested in helping, set up a clinic in the region. The community members were recruited to participate in a study designed to uncover the cause of the medical scourge and pave the way for biomedical interventions.

Much of that research was organized around the search for a “thrifty genotype.” Geneticists at the time thought that diabetes had a natural biological explanation. Humans in the distant past had a feast-or-famine relationship to food; hunter-gatherers might kill a giant ground sloth one day only to then go without a meal for quite some time. In response to this caloric environment, the story went, our ancient ancestors became genetically equipped with a metabolic ability to absorb and store energy for long periods. Diabetes was the result of this thrifty genotype being deposited in modern society where food was abundant.

Indigenous communities across the globe were known to have some of the highest rates of diabetes; the Akimel O’odham were just the most extreme example. Geneticists thought the thrifty genotype could explain both diabetes generally and the health disparities associated with it. If some group had a particularly high rate of diabetes, then that must be because they had a particular form of the thrifty genotype. The researchers thus embarked on an effort to save the Akimel O’odham by finding their genetic predisposition to diabetes.

In the decades that followed, all that attention to what was going on inside the bodies of the Indigenous community proved scientifically valuable. The basic endocrinology of diabetes, the relationship between diabetes and obesity, the progression from diabetes to kidney failure — these insights and many others relied on data that the Gila River Indian Community members provided.

The Akimel O’odham, however, benefited little. That’s because the source of the epidemic wasn’t inside their bodies. It was all around them.

“Akimel O’odham” means “River People.” For centuries, they lived off the Gila River that runs through the parched Sonoran Desert, using it to irrigate fertile farmland. They grew beans, squash and cotton.

In 1859, after the Mexican-American War and the Gadsden Purchase, the United States took control of the area and established a reservation along the Gila River. Soon after, white ranchers and farmers up river began diverting water, leaving little for the Akimel O’odham. A horrific famine took hold for 40 years.

The federal government eventually intervened, providing the Indigenous community with surplus commodity foods. That solved the threat of starvation, but it introduced a new threat. The supplies consisted of things like lard, refined sugar, white flour and canned meats. Fresh produce wasn’t included until the 1990s. A health survey of the Akimel O’odham at the beginning of the 20th century revealed a single case of diabetes among their people. By the 1960s, almost half the adults had it. The problem wasn’t with the way that their bodies metabolized food; the problem was with the food that their bodies were made to metabolize.

By the 21st century, the Gila River Indian Community became frustrated with the results of their decades-long commitment. The scientists were publishing hundreds of papers about the biology of diabetes, but the disease continued to devastate. The community collectively decided to end active participation in the study, shifting their attention and resources toward research that was focused on prevention and public health.

Sixty years after federal scientists first discovered the diabetes epidemic afflicting the Akimel O’odham, that episode offers a powerful lesson for personalized medicine ambitions of the present. Geneticists today don’t talk about a “thrifty genotype” anymore. That pseudoscientific idea has been expunged from scientific discourse. But the thought that there must be some simple, biological explanation for complex, social problems remains at the heart of personalized medicine.

That inclination distracts from the actual causes of health disparities. It reinforces the idea that health disparities aren’t something that we need to collectively fix in society; rather, they’re something that people of color need to fix in their genomes. It violates the trust of those who put their faith in a science that promised to help them. And, ultimately, it exacerbates the problem it was intended to resolve.