Julio Berdegué is the assistant director-general and regional representative for Latin America and the Caribbean for the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization.

The covid-19 pandemic has pummeled the globe, harming the health of the planet and its peoples. In Latin America, the economic blows have fallen with particular force.

Across the region, resources that might once have been used to protect forests — which are among Latin America’s biggest contributions to fighting climate change — have been channeled into shoring up the economy and battling the disease.

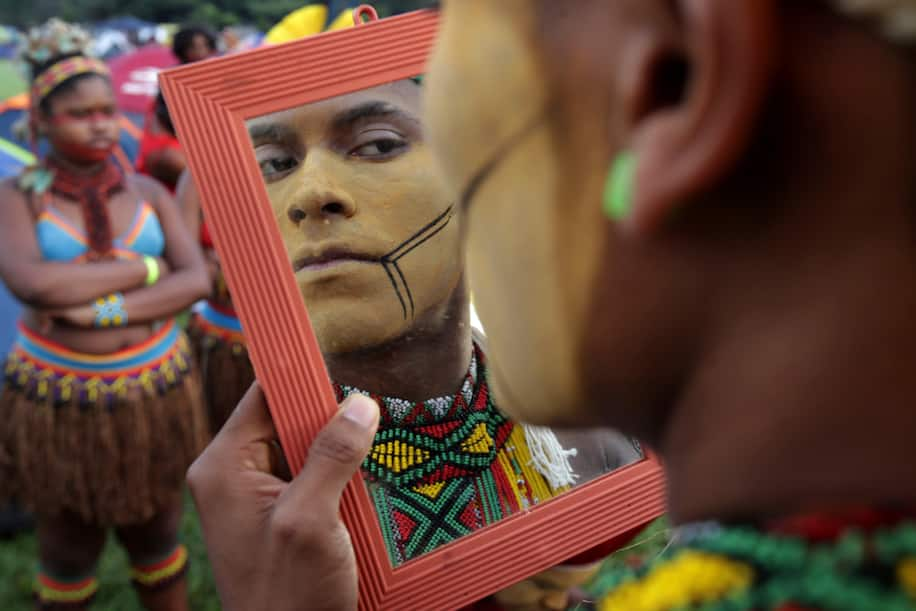

This means that Indigenous communities in these forests often are confronting not only the deadly covid-19 virus, but an unprecedented invasion of their ancestral territories, as illegal loggers, drug lords, ranchers, miners and many other groups take advantage of the cover of the pandemic.

There are some bright spots in this story, however. In Panama, a recent decision by the country’s supreme court suggests governments do not have to choose between economic recovery and the conservation of tropical forests, even as a modern-day plague continues to hold humanity hostage.

In October, the Panama Court ruled that the Naso People could establish their own comarca — the country’s term for a protected indigenous territory — on land that included areas the Naso had lost to protected areas decades earlier. In doing so, the court chose a course that promises to address the economic, social and cultural needs of a people whose youth might otherwise be forced to travel north.

The rate of deforestation within the Naso lands has been almost one-tenth of the government-protected conservation areas, including the La Amistad International Park (PILA) and the Palo Seco Protected Forest (BPPS). These protected areas both ceded land to the Naso last year, adding significantly to the size of the newly titled comarca.

These deforestation rates are seen in recent scientific research from across Latin America, which suggests that granting the Naso and other Indigenous and tribal peoples territorial rights is an affordable and effective solution for meeting a country’s climate action goals.

Amid a global health and economic crisis brought on by the pandemic, scientists have made us aware of the value of standing forests for preventing the emergence of potentially dangerous pathogens. Even before the start of the pandemic, the World Economic Forum estimated that intact ecosystems are worth $33 trillion to the global economic sector.

We have compiled more than 300 studies published in the last two decades showing how effectively and sustainably Indigenous and Tribal Peoples manage their territories. The research also suggests that their protective role is increasingly at risk, at a time when the Amazon is nearing a tipping point, with worrisome impacts on rainfall and temperature, and, eventually, on food production and the global climate.

Between 2000 and 2012, in the Bolivian, Brazilian, and Colombian Amazon, deforestation rates in Indigenous territories were only one-third to one-half the rates in other forests with similar ecological characteristics. The best results are seen in indigenous territories where communities have gained recognition of collective legal titles to their lands — for many others, the struggle for recognition of their property rights distracts from effective forest management.

While the impact of guaranteeing tenure security is great, the cost is low: only $6 is needed to title a hectare of Indigenous land in Colombia, $45 in Bolivia and $68 in Brazil. These figures were found to be 5 to 42 times lower than carbon capture technologies for both coal- and gas-fired power plants, and, when you factor in the cost of comparable economic stimulus, the benefits of recognizing Indigenous land rights tower over alternative ways forward.

We need to look at the rainforests as the source for drinking and agricultural water, as well as vital stores of carbon that need to stay in place. Indigenous and Tribal Peoples should be compensated for their stewardship of these vital ecosystems, as the benefits extend to the regions downstream of Indigenous and tribal territories as well as the entire world. This compensation should begin with recognition of the territories they have managed for generations.

No country in Latin America has the financial capability to address each crisis individually. And we just do not have the time to wait for the judicial system to step in to provide relief, like it did in Panama with the Naso People.

Now, more than ever, it is fundamental that we find investments that can help us to recover from the pandemic, but also contribute to the inescapable task of mitigating and adapting to climate change. Collaborating hand in hand with Indigenous and tribal peoples is an effective solution for many of the challenges on the table right now. It is past time that we embrace it.