Yes, even during the coronavirus.

By Miranda Featherstone

Ms. Featherstone is a writer and social worker.

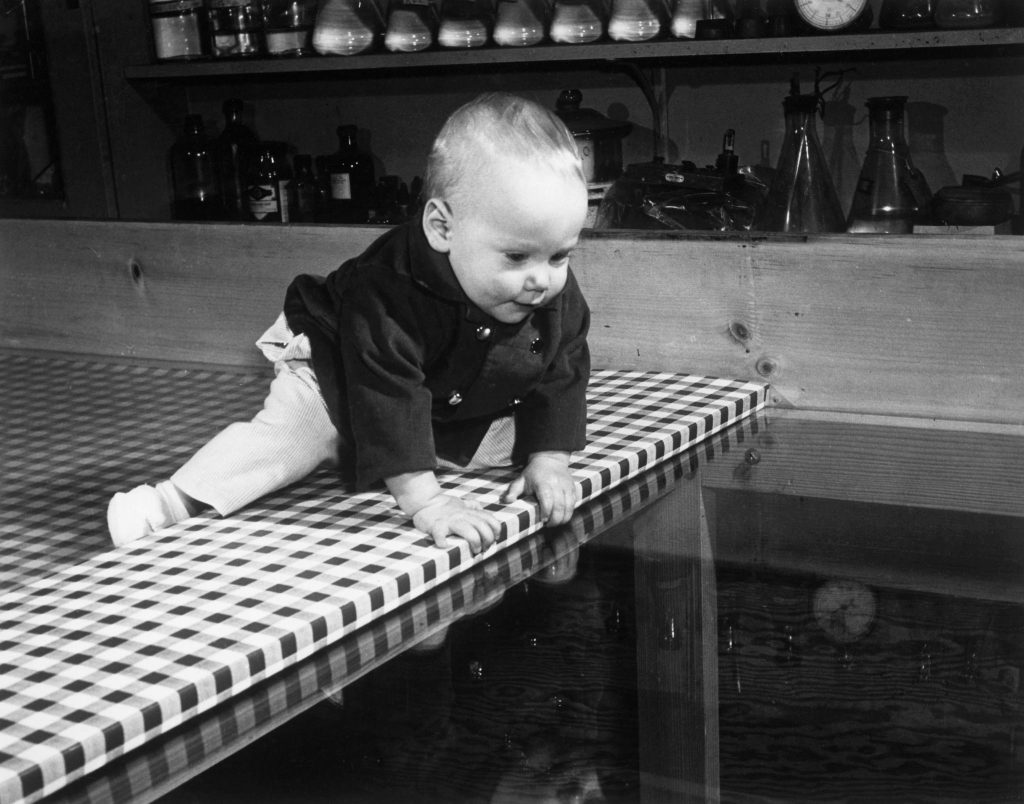

In a 1960 study, babies were coaxed by their mothers to crawl atop plexiglass over a sharp drop in the floor. The surface was smooth, and safe, but appeared perilous to the hapless infants. It was the “visual cliff” experiment, a classic of developmental psychology, meant to demonstrate something about infant depth perception.

I have long remembered the follow-up: Researchers in the mid-1980s wanted to know if the mother’s facial expression would affect the baby’s odds of risking the perceived danger. It turns out that mothers who made joyful or interested faces reassured their babies that the cliff was not a threat. Those babies observed the cliff, checked their mothers’ faces, and crossed anyway — unlike the babies of mothers who made fearful or angry faces.

My 2-year old son and I walk, masked, through our Philadelphia neighborhood early one morning. He trails behind me, and every so often I turn to watch him. The streets are empty, and then a dog-walker appears. I extend my hand and call my son’s name: “Tomás.” My tone aspires to be casual, but I am not using his usual nickname. He scampers toward me and takes my hand. Sometimes I don’t even have to call — the extended hand is enough.

“Look at the doggie!” I offer in a jaunty tone, trying to neutralize the strangeness of the ritual. We walk hand in hand until they pass; he wriggles his fingers out of my grasp as soon as he feels me relax. He is paying attention.

Which mother am I, in the experiment? I am trying to be encouraging, calm. But, like many parents in the midst of the pandemic, I am teaching my son to be afraid of the world in a host of implicit and explicit ways. He is too young to understand about asymptomatic carriers and ventilators: what he knows is that now I am worried when we are outside and he is not near. He knows that the places he loves have not been safe (“Library closed,” he intones solemnly at dinnertime. “School closed. Playground closed.”).

Since March, people like me have been able to keep their families extremely isolated, thanks to white-collar work-from-home policies, single-family housing, and scores of other privileges. But as cities and towns reopen, driven not by safety but by politics, I will have to decide on the parameters of his “new normal.”

Will we return to the local tot lot, where toddlers delight in sneezing into one another’s open mouths? Can we leave Tomás in the care of a cautious friend, with children of her own, while I scramble to compress three weeks’ worth of work into a morning? And, crucially: When will we send him back to his beloved preschool?

Mid-century psychoanalysts such as Margaret Mahler posited that toddlerhood — roughly the time between the ages of 1 and 3 years — is a critical moment for children to be able to explore the world while knowing that their parents are comfortable with this exploration and nearby when needed. To tell children that the world is too dangerous for them to explore is to foster fear, a lack of confidence, or perhaps, defiance born out of thwarted efforts toward independence.

For kids returning to day care and other settings where they will interact with people outside their household following the strange time in isolation, we can anticipate meltdowns and weeping in the short-term, and anxiety in the long run. The return will be more challenging if re-entry is delayed indefinitely, or if parents project their own apprehension and hesitation when the time comes to return to school.

One important task for adults supporting young children in re-entry is to abandon the myth that children — or any of us — can be completely isolated from exposure. There is no cure for Covid-19, and no vaccine, nor is it clear when either of these might materialize. But this cannot mean that children remain isolated for months, or even years.

The perfectly secure and sanitized environment is perhaps a delusion of the elite — largely the white elite. Black families have long been compelled to weigh the realities of racist policing and other dangers against the need for children to practice independence and forge social bonds outside the home. The possibility of harm does not preclude exploration and independence; rather, it means that we take reasonable precautions, and instruct kids frankly about safety and risk.

As communities begin to open up, how might we mitigate risk of exposure to illness while allowing our children to interact with others? For some this might mean podding with another family to share in the burden of child care, socializing with friends outdoors, or simply talking excitedly with children about future social interactions.

For many of us, it may mean that we send our children back to a safety-conscious day care as soon as possible — feigning cheerful calm for our children. Recent evidence from child care centers that have remained open during the pandemic suggests that with the right precautions children are not terribly likely to be vectors of transmission to adults. We must take a harm-reduction approach toward child care, advocating for the safety of kids and adult workers, while allowing children access to the world beyond their iPads and the stressed, overworked grown-ups they’ve been living with.

It will be important for adults to give even the youngest children language for what is happening: “We haven’t been in school because we didn’t want to spread coronavirus germs. But soon we will go back to school. There still might be germs, but we are going to be very careful so that we won’t spread them.” The threat is not vague and unspeakable; it may be invisible, but it is describable and specific.

Our impulse is often to avoid giving kids potentially overwhelming information, but what we know is that a lack of explanation and communication can be quite terrifying in and of itself, leaving explanations to kids’ amateur imaginations. Language allows young children to symbolize and contain their experience, the first step to understanding and regulating emotions.

Children require repetition of news. We will find ourselves explaining again and again that Teacher Laura will be wearing a mask but that she will still be Teacher Laura, and that they really, truly, seriously, like I said yesterday, must not pick their nose.

“You’re going to go back to school soon,” I tell Tomás.

“I sit on a chair at ’cool,” he tells me, with the wistful air of Proust remembering a madeleine.

“Yes,” I say. “You sit in a chair! There will still be germs, but you and me and Papa and your sister and your teachers are going to be really careful so that the germs don’t spread.” He nods, a mix of eager and serious.

I will tell him this again and again. I will sometimes say the wrong thing; he will sometimes misinterpret my words. But over the coming weeks, he will begin to understand what is happening. I cannot guarantee our safety. But I must encourage him to go forth into the land of smocks, rice cakes, and very small wash basins, where he will continue with the project of becoming a small person in a large, imperfect world.

Miranda Featherstone is a writer and social worker. She lives with her family in Philadelphia.