This is part two of a five-part story published in partnership with the Center for Public Integrity and Word In Black.

WATERLOO, Iowa — The book of “miscellaneous” records was a deep red. Inside, white type on black paper detailed in dry language the restrictions the homeowners of Waterloo’s well-to-do Highland neighborhood banded together to place on their propertiesin 1945.

No low-cost homes, no small lots, no businesses — and no owners or tenants “of any race other than the Caucasian race.”

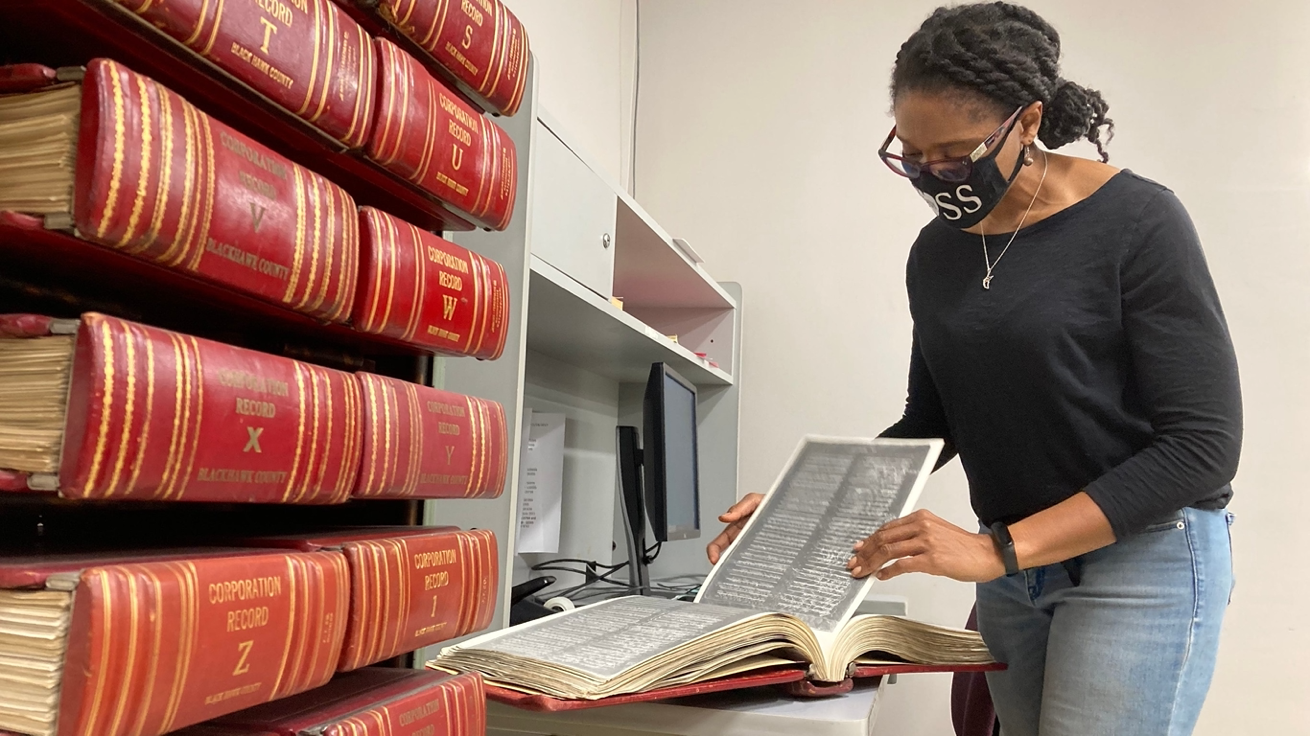

ReShonda Young leaned over the bookin the county recorder’s office, looking at the 18 pages of signatures of people who once lived in what is now her neighborhood, each of them intent on keeping it all white.

Redlining real estate: keeping America separate and unequal

The restrictive covenants that spread in Waterloo and across the country were just one skirmish in a long campaign by the government, banks, real estate agents and myriad other combatants to keep America separate and unequal. For decades, Black residents in Waterloo could live only in a small part of the city hemmed in by railroad tracks and factories.

By the 1930s, federal employees were making maps of U.S. cities that deemed certain areas “hazardous” for investment, a practice that came to be known as redlining. They offered just one reason they shaded that part of Waterloo red: “This is the colored section.”

As a child, Young would walk through the Highland neighborhood, passing by the pocket park, the mature trees, the inviting early 20th-century homes in contrasting styles, and dream of living there. And when she grew up,she made it happen, finding a deal on a cozy blue house.

In a sense, her moving there meant the white-collar white supremacists who erected those earlier barriers had lost.

But in another sense, they hadalready won.

Racial wealth gap stretches on

Congress passed anti-discrimination laws in the 1960s and ’70s to try to stop racially biased decisions in hiring, real estate and lending. But the country never fixed the wealth gap that generations of that discrimination created, locking those disparities into place.

Half a century later, Black households headed by a college graduate have a lower median net worth than white households headed by a high school dropout, according to research by Duke University’s William Darity Jr., a veteran researcher on the wealth gap, and other scholars.

Less family wealth means more student-loan debt. More trouble when emergencies hit. More difficulties buying homes or starting businesses. Running hard might do nothing more than keep you from falling further behind, even if no further discrimination piles on.

Young, who wrote an opinion piece for the Des Moines Register in 2020 calling the situation “an impossible race,” looked at the once-legal document under her fingertips and thought of the insidious equivalents today. Lower property appraisals, biased loan denials, real estate agents steering clients to or away from neighborhoods based on their race.

It all feels harder to fight because none of it comes with a blunt written statement like the one staring back at her.

“This is in-your-face,” she murmured. “You know where you stand.”

Surviving bankruptcy, overcoming racial discrimination

Young grew up a few blocks south of the redlined community that was once the only place Black residents could live in Waterloo. And she was born just two years after the local school system approved a desegregation plan over strenuous objections from a well-organized group of largely white parents who said they objected to mandatory busing.

Up until that point, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights noted, many of the district’s white teachers “had never met a Black person.”

For years, Young said, she was passed over for gifted and talented classes in school despite having excellent grades. It made her more determined. She graduated in the top five of her high school class and won scholarships for college, part of the first generation in her family to go.

That same determination runs through her working life, starting with her first summer job. Young said that after she put in a day of exhausting fieldwork at age 14, struggling to quickly remove the pollen-producing tassels from corn, a supervisor told her not to bother coming back. She was certain she could do much better her second day — and just as sure that no one would notice if she returned.

Young said she was right on both counts: She quickly worked her way onto the fastest crew.

She’s tapped that resolve many times since.

Young bought rental property atthe age of 25 while repairing her credit after her identity was stolen. She repaired her credit again after her first business partnership went sour and she filed for bankruptcy protection.

She started a gourmet popcorn business with a loan smaller than she’d needed, franchised it and sold it. She sued the federal government and won. And she negotiated a settlement from a bank whose error she says triggered a domino effect leading to her second bankruptcy.

Young has also worked for investment and financial services companies — unusual in the Waterloo region, where whites are employed in finance jobs at three times the rate of Black residents, U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission records show.

But she’s never worked at a bank.

A prayer amid the Covid-19 pandemic

Still not entirely sure she should try to open one, Young texted a cousin with two decades of banking experience and expected to hear it was too big an idea to take on.

Instead, her cousin wanted in.

It was April 2020, a month after health officials declared the coronavirus a pandemic and a month before George Floyd’s murder. “OK,” she thought in a silent prayer, “if this is really something I’m supposed to do, I need You to give it a name.”

Soon after, in the middle of doing laundry, she had the strong sense that she needed to read the verses of 1 Chronicles about Jabez, who was “more honorable than his brothers.”

“Jabez cried out to the God of Israel, ‘Oh, that you would bless me and enlarge my territory! Let your hand be with me, and keep me from harm so that I will be free from pain.’ And God granted his request.”

She stopped thinking about the bank as something she might do. It would be the Bank of Jabez. And she was going to open it.

You can hear a podcast about Young’s quest in the newest season of The Heist.

Jamie Smith Hopkins is a senior reporter and editor at the Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit newsroom that investigates inequality. She can be reached at jhopkins@publicintegrity.org. Follow her on Twitter at @jsmithhopkins.