Religious and spiritual traditions have, for millennia, provided beliefs, practices, rituals, services and communities where individuals gather to make sense of life, support one another, and seek the transcendent. Recent empirical research indicates that religious service attendance is associated with a large number of important health and well-being outcomes.

Large longitudinal studies, following thousands of participants over time, and controlling for a host of other factors, have found that religious service attendance is associated with improvements in longevity, cancer and cardiovascular disease survival, social support, meaning in life, life satisfaction, volunteering, and civic engagement. Other mental health and social benefits include reductions in depression, suicide, smoking, substance use disorder, and divorce.

Participation in other forms of relational and community life, likewise, has important effects on health. However, the size of the effects of religious community participation tend to exceed those of other forms of social participation. With regard to studies on mortality, suicide, and cardiovascular disease, the effects of religious service participation appear larger than for other social participation indicators examined in these studies, including marriage, time spent with friends or family, hours spent in other community groups, or even their combination.

While the empirical research itself has become increasingly clear, the implications require nuanced consideration. In particular, these results do not necessarily mean that everyone should immediately join a religious community. People do not typically become religious for reasons of physical health. Rather, religious commitments and beliefs are fundamentally shaped by values, relationships, upbringing, experiences, systems of meaning, evidence, and truth claims. While the implications of the research thus need to be approached carefully, my colleagues, Drs. Howard Koh and Tracy Balboni, and I recently argued in the American Journal of Epidemiology, that there are indeed important implications for public health.

While the research in no way suggests a universal “prescription” for religious service attendance, it does perhaps constitute an invitation back into communal religious life for those who might already positively self-identify with a religious tradition.

While the research in no way suggests a universal “prescription” for religious service attendance, it does perhaps constitute an invitation back into communal religious life for those who might already positively self-identify with a religious tradition. Within clinical or health promotion contexts, religious service attendance could, in principle, be promoted for those who already positively self-identify with a religious tradition. And other forms of community life could be promoted for those who do not.

Within clinical contexts, clinicians can take a short spiritual history with relatively neutral questions such as, “Are religion or spirituality important to you in thinking about health and illness, or at other times?” and “Do you have, or would you like to have, someone to talk to about religious or spiritual matters?” Such questions can be asked even if clinicians and patients do not share similar religious views.

For patients who positively identify with a religious or spiritual tradition, clinicians could also inquire about and even encourage communal involvement, when appropriate. And again, for patients without such beliefs and affiliations, other forms of community involvement can likewise be encouraged. For patients who have suffered negative experiences or even abuse from religious communities, these relatively neutral questions may help uncover trauma and prompt empathy, support, and referrals to other care providers. Both anecdotal evidence and studies of patient experience suggest that, when these issues are handled in a patient-centered fashion, raising questions of religion or spirituality within the clinical context can be nearly universally positive.

Public health promotion efforts could likewise, if done sensitively, encourage various forms of community participation. Health promotion campaigns can inform the public about health benefits of community participation, and provide a list of local opportunities, including but not restricted to, religious service attendance. While such efforts in the United States are limited, these sorts of practices saw dramatic increase in clinical and public health contexts within the United Kingdom over a few short years. Religion and spirituality can be sensitive topics. But, if we engage in these conversations thoughtfully and ethically, their potential to contribute to population health may be very substantial indeed.

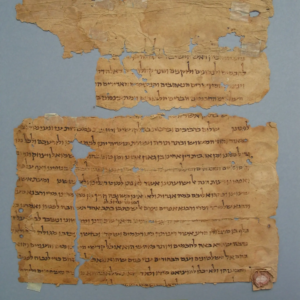

Photo via Getty Images

Tyler J. VanderWeele, Ph.D., is the John L. Loeb and Frances Lehman Loeb Professor of Epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and Director of the Human Flourishing Program at Harvard University. His empirical research spans psychiatric and social epidemiology; the science of happiness and flourishing; and the study of religion and health. He has published over four hundred papers in peer-reviewed journals; is author of the books Explanation in Causal Inference (2015), Modern Epidemiology (2021), and Measuring Well-Being (2021); and he also writes a monthly blog posting on topics related to human flourishing for Psychology Today.