Shortly after the US Constitution was ratified, Benjamin Franklin penned a letter to French scientist Jean-Baptiste Le Roy, in which he said that “in this world, nothing is certain except death and taxes.” While certain, death can come in a myriad of ways, and if we peel back behind some of the leading causes of death, we find that chronic stress is linked to six of them.

Stress, like most health issues, is not equally distributed across racial groups. Black adults are 20 percent more likely to report serious psychological distress compared to white adults. Those who live in poverty and face daily struggles of overpoliced neighborhoods, underfunded schools, and lower-paid jobs are two to three times more likely to report serious psychological distress.

The psychological effects of these economic disadvantages don’t only affect parents, but they also heavily impact children, even before they are born. Studies have shown that prenatal stress can have significant effects beginning in the womb and spanning across a lifetime.

This stress, according to experts, can arise from traumatic experiences, life-changing events, or daily microaggressions. And it has negative influences not only on the outcome of the pregnancy, but also on the behavioral and physiological development of the child. Threatening situations, no matter how big or small, increase the body’s heart rate, blood pressure, and the pace of breathing.

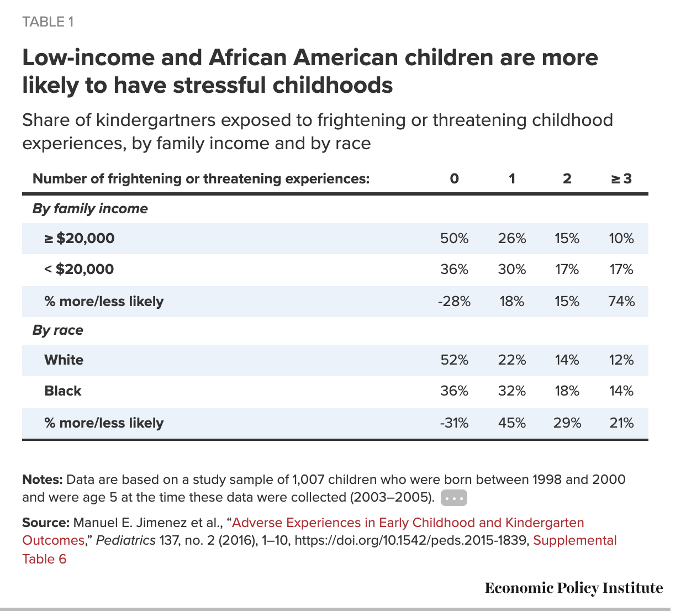

For Black families, particularly those dealing with the weight of poverty, threatening situations are plentiful. According to the Economic Policy Institute, 64 percent of Black children have been exposed to one or more frightening or threatening experiences, while only 48 percent of white children are.

When accumulated, trauma—which is the emotional, psychological, physical, and neurological response to stress—can lead to adverse effects. From daily racial microaggressions to lethal encounters, when children are frequently exposed to sustained traumatic events, they are more likely to have adverse behavioral effects and/or suffer from depression.

A study launched by Dr. Monnica Williams, a psychologist based at the University of Ottawa, found that Black students who reported higher rates of perceived discrimination had higher rates of alienation, anxiety, and stress about future negative events.

Each generation of Black Americans has faced horrific forms of racial discrimination whose scars they still carry today. The vestiges of slavery can be seen through our mass incarceration policies. Police officers, stationed around the clock in Black neighborhoods, evolved from plantation overseers. Even our economy, as detailed in the New York Times’ 1619 Project, has the fingerprints of slavery all over it. This history, and our current experiences, does not simply affect people in one single moment in time.

As a report from the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America (N’COBRA) published last year—titled The Harm is In Our Genes: Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance & Systemic Racism in the United States—details, the trauma stemming from enslavement, Jim Crow, mass incarceration, the war on drugs, and police terror can be passed down across generations through epigenetic change.

The idea that trauma can be inherited and therefore alter how a person’s genes function (epigenetic change) is not new. It was first introduced in 1967 by Dr. Vivian Morris Rakoff, a Canadian psychiatrist who recorded elevated rates of psychological distress among the children of Holocaust survivors.

His initial research, which has been supported by subsequent studies, has found that the children and descendants of Holocaust survivors had higher levels of childhood trauma, increased vulnerability to PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), and other psychiatric disorders. In one of his earlier papers, Rakoff wrote that “the parents are not broken conspicuously, yet their children, all of whom were born after the Holocaust, display severe psychiatric symptomatology. It would almost be easier to believe that they, rather than their parents, had suffered the corrupting, searing hell.”

Other studies have examined the intergenerational effects on First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples in residential schools run by the Canadian government for over a century. They found that children and in some cases grandchildren of those who attended these schools were more likely to report psychological distress, suicide attempts, and learning difficulties.

Can Reparations Heal?

Just as educators cooperated in carrying out genocidal policies through their participation in residential schools (in the United States, as well as in Canada), the medical industry has its own sorry history. For a long time, many in that field justified racial health disparities through racist and mythical biological arguments that claimed Black people were inherently inferior to white people. This US mental model was thoroughly used throughout the antebellum period and beyond. It is the root of the early 20th-century eugenics movement that led to the sterilization of thousands of Black people and was a source of inspiration for Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf and South African apartheid.

The notion that the medical industry has played a role in strengthening white supremacist theories and fortifying a racial caste system is one that I don’t believe many can argue with. The question at hand remains: what do reparations look like within a health context?

Reparations and Trauma

Large-scale trauma affects people in multiple ways, explains Dr. Yael Daniel, a prominent researcher in the field of intergenerational trauma and founder of the International Center for the Study, Prevention, and Treatment of Multigenerational Legacies of Trauma. It only makes sense then that our solutions are also multifaceted.

A trauma-informed framework must be applied to any reparations effort to ensure that we are creating a sustainable social policy that uproots the tenets of white supremacy. This approach, according to experts, should go seek to go beyond broad notions of trauma and address specific sociopolitical and economic drivers. Trauma-informed care within a context of reparations means employing a holistic focus not only on the economic impact of the legacy of slavery but also its psychological and health impact.

Acknowledgment of Harm

An admission that harm was done is one of the first needed steps on the road to racial repair. While it has had its critics, acknowledgment of past wrongs to those who were harmed by them was a core component of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Accepting responsibility for harm that was caused is a necessary step in a reparation process by creating the space for the responsible party to admit wrongdoing, and the harmed party to have the choice to start a healing process.