In the early 1960s, Evanston resident Brenda Phillips’s parents bought their first home in the fifth ward. Her family of five moved into the two-bedroom house after taking out high-interest loans, and Phillips was eventually bussed to a new school as part of desegregation efforts.

Housing is “where the initial harm took place,” Phillips said.

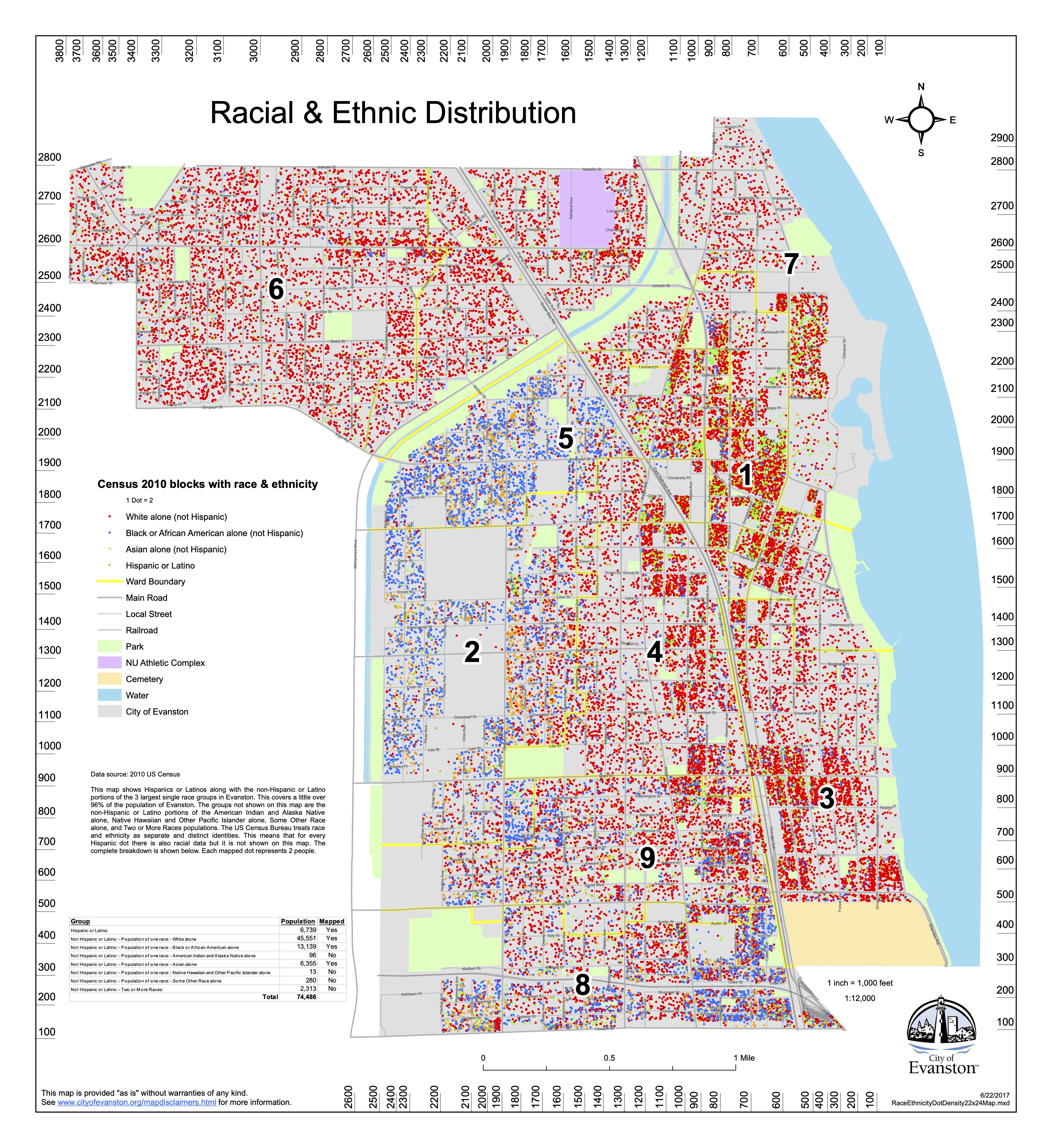

A cursory glance at the racial demographics mapped across Evanston’s nine wards shows the legacy of segregation. Redlining and housing discrimination have long been issues in Evanston – and it’s what the recent reparations housing program hopes to address.

A national spotlight fixated on Evanston as it became the first city in the U.S. to pass legislation providing reparations to Black Americans. But the city is divided over its first initiative, which will provide up to $25,000 of housing assistance to a limited number of Black households in Evanston that apply for the funds.

What the housing program accomplishments, and how it falls short

Some critics say the housing program is not true reparations because it does not go far enough to redress slavery, which was the original intent of reparations for Black Americans who could trace their lineage to an ancestor who was enslaved. Some defenders of the program say it is only the first step, as it draws on only $400,000 of $10 million allocated to Evanston’s reparations fund. Applications for the housing program funds will be accepted beginning this summer.

All applicants must be Black or African American and currently reside in Evanston, according to a draft of the current guidelines. Beyond that, they can qualify for funding through meeting different criteria. One way is to prove they lived in Evanston sometime between 1919 and 1969, when many discriminatory housing policies harmed Black residents. Another way is to prove they are descended from someone who lived in Evanston during that time period. A third way to qualify is through proving that applicants experienced discriminatory housing practices after 1969. Applicants will be prioritized for receiving funds in the above order.

The focus on housing as a first step in this process comes from community input and research. Historian Dino Robinson of the Shorefront Legacy Center in Evanston co-authored a report upon request from the city that highlighted discriminatory and racist policies that historically harmed Black residents.

Robinson is concerned that the initiative’s scope is being too narrowly interpreted.

“What frustrates me the most is how, at least at this first initial program, everybody’s hyper-focused on just the housing aspect of it and completely ignoring that there are two other components to this as well: the economic development and educational initiatives,” Robinson said.

A resolution from November 2019 identified housing, economic development and education as three initial areas of focus for reparations. The current reparations page on the city of Evanston website adds finances and history/culture to that list.

The question of national reparations has been in the news too. The House Judiciary Committee recently voted to advance H.R. 40, which would create a commission to study slavery and discrimination in the U.S. and “recommend appropriate remedies.”

As this conversation unfolds at both local and national levels, Robinson clarified that Evanston’s reparations are “not in competition or replacement of what a national model could look like.” He added that municipal actions like those in Evanston work toward “forcing the hand” of the federal government.

Robinson also highlighted the potential of the federal government to deliver what some Evanston residents are asking for: direct cash payments as reparations.

“I think a lot of people are focused on true reparations as only a cash payout. And you know, I agree with that, in many cases, but that’s something that the federal government has to do,” he said.

His reasoning is that people who receive cash payouts from a local municipality will be automatically taxed up to 28%. Cities and towns cannot override that tax, he said, but another entity can.

“The federal government has control of that, so in order for that to happen, the federal government needs to talk to the United States Treasury and figure that process out,” Robinson said.

Uncertainties about the housing program

Some critics of the recent housing program formed Evanston Rejects Racist Reparations, also referred to as E3R. The group has been vocal about its disapproval of reparations initially taking the form of a housing assistance program.

“We felt that the bill that was passed as reparations didn’t necessarily meet the qualifications of reparations, and so our objective for the campaign was to get the word reparations removed from the bill,” said Jersey Shabazz, an organizer of E3R who currently lives in Rogers Park but formerly lived in Evanston. “We were not interested in stopping that particular bill at all.”

Shabazz emphasized that he does not believe that community improvement and rectifying harm are necessarily reparations.

“The housing program is violence, because if you allow a housing program to pass as reparations, then they leave that door open for anything else that white people deem reasonable to be considered reparations,” he said. “So then public aid becomes reparations, and programs that we will say are socialist, then that becomes reparations. So the common good becomes a form of repair, when really that’s what cities and states should be doing anyway.”

Although the housing program passed on March 22, Shabazz said that E3R will still continue its advocacy work. He said that “the commitment that we have to ensuring Black liberation goes beyond this bill.” In the same vein, he said the organization is looking into becoming a registered 501(c)(4) organization, holding teach-ins and connecting with other organizations and networks nationwide.

Like Shabazz, Phillips has some questions about whether the program is truly reparations.

“Now that’s not to say that the program of reparations won’t evolve into something bigger and greater, but certainly there are enough questions I think that surround it today that make me think – make a lot of people think – is this really a program of reparations, or is it just an equitable housing plan?” Phillips said.

Even though she said the reparations process is not perfect, Phillips believes it can improve over time, and that provides hope for other cities that are considering reparations too. She likened reparations to an invention evolving from a prototype to a working product.

“One of the things that Alderman [Robin Rue] Simmons has said is that this is where we are starting, and I think that’s very, very important,” Phillips said. “We have to start somewhere. She’s acknowledged that it’s not the perfect plan, but that it will go through various iterations until we get to something that looks a lot more like a reparations plan should look.”

The housing program made it through City Council with an 8-1 vote, but debate around it continues. This discourse has fueled conversations about how to move forward. Phillips said it is important for people to continue advocating for something better and for the city to reflect on what already passed to see if it is effective.

“As a community, we have to push for that level of perfection,” she said. “We have to push for constant improvement, we have to push for continuous review.”

Over time, Phillips says that self-determination should be the goal of reparations.

“There has to be a point at which reparations becomes an issue that allows an individual to determine their own destiny because of it. A more positive destiny,” Phillips said. “So however many times it takes us to get there I think that’s where we have to get to.”

She also drew a comparison to the post-Civil War “40 acres and a mule” plan, from which H.R. 40 derives its name. The plan, which would have given many formerly enslaved people 40 acres of land to do with what they chose, was later repealed by President Andrew Johnson. Though “40 acres and a mule” does not exactly fit into today’s world, Phillips argued that a similar concept should be carried out through contemporary reparations.

“In the spirit of what that 40 acres and a mule would have done for an individual who had just been released from oppression, it would have allowed that individual to define and determine his or her own destiny,” Phillips said. “We have to be able to give people the tools that will enable them to define their own destiny.”

Reparations for past harm – amid ongoing violence

Conversations about reparations have trickled into the church, according to Rev. Rosalind K. Shorter Henderson, who is the senior pastor at Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church. In open discussion within the congregation, members have brought up reparations and discussed attending meetings about reparations.

“And so there’s discussions behind [reparations] about how it’s really good, we think that’s something that should happen,” Rev. Henderson said. “The question is how to disperse the money. That’s the big question right now.

Against the backdrop of recent police brutality against Black people and other people of color, Rev. Henderson has used the Scripture and her sermons to address this harm. She said that although reparations can attempt to repair past harm, injustice perseveres.

“Reparations, yes, may be some justice for something that happened during slavery, but we’re talking about things that happened right today,” Rev. Henderson said.

Like Rev. Henderson, Shabazz also connected police violence to the question of reparations.

“I’m just going to say that policing is certainly a relic, an extension of slavery, and so I don’t think that we can authentically provide reparations without addressing and without divesting from and defunding policing,” he said.

Reparations should not only redress past violence but also ensure its “cessation” going forward, according to Shabazz. To retrospectively repair harm and proactively ensure that harm does not occur, Shabazz said this must include a systematic overhaul.

“What we’re really asking for, and I think that this scares folks the most, is we’re really asking for a new order of existence,” he said.

Graphic by Meher Yeda / North by Northwestern.