This Lorraine Hansberry play, set in the 1960s in a fictional African country, speaks incisively to the American present.

When New York theaters reopen — in January, or next spring, or when some epidemiological genius figures out how to make enclosed spaces with cramped seating even passably hygienic — I have a suggestion: Revive Lorraine Hansberry’s “Les Blancs.” This drama, unfinished at her death in 1965, and completed by her former husband, had a monthlong run on Broadway in 1970. In 2016, the South African director Yaël Farber, the dramaturge Drew Lichtenberg and Joi Gresham, the literary executor of Hansberry’s estate, collaborated on a revised version of the script, which then ran at London’s National Theater.

Now National Theater at Home has made the production available for streaming on its dedicated YouTube channel, through Thursday. Haunting, haunted, devastating, it’s a work of the past that speaks — lucidly and startlingly — to the confusions of the present.

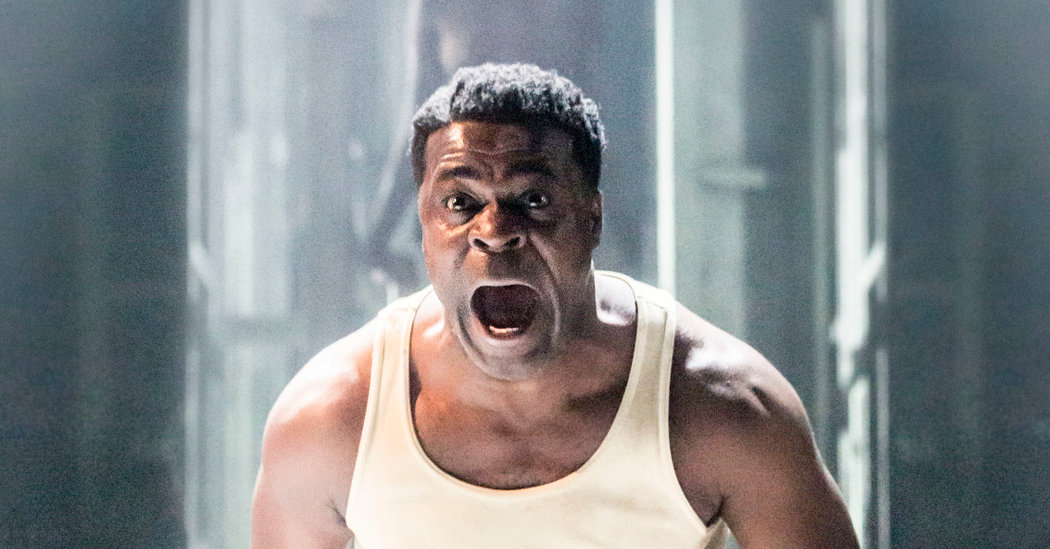

Set in Ztembe, a fictional African country, the play begins with the arrival of Charlie Morris (Elliot Cowan), a white American journalist, at a rural mission. Reporting on Ztembe’s struggle for independence, he hopes to interview Tshembe Matoseh (Danny Sapani), an intellectual who has returned home to bury his father. Tshembe lives in England. He has a white wife and a young son. While he sympathizes with the revolt, he doesn’t see himself joining it. But his time at the mission and his interactions with his brothers — Abioseh, who is in training to become a Catholic priest, and Eric, the product of his mother’s rape by an English officer — make the conflict personal and necessary.

In Farber’s production, bathed in Tim Lutkin’s tenebrous lighting, a skeletal outline of the mission revolves on a carousel. (The designer is Soutra Gilmour.) Around the mission stand the Black characters, including a group of women who sing in the Xhosa split-tone style as they trail smoke and incense. Under Farber’s direction, the play moves away from realism and toward expressionism, even as it becomes a kind of ghost story, in the sense that no one participating in colonialism — as oppressor, oppressed or ostensibly neutral observer — can ever be fully alive.

Farber is a powerful director, not a subtle one. But the play, unfinished and purposefully unresolved, has a way of sidestepping easy moral judgment. Not that Hansberry indulges relativism or both-sides-ism. She portrays whiteness, not blackness, as the “other,” and refuses to see the revolution as more violent than the regime that provokes it.

Charlie’s character, a seeming audience surrogate, has to reckon with his own blinkered perspective and culpability. “White rule, Black rule, they’re not very different,” he tells Tshembe.

“I don’t know, Mr. Morris,” Tshembe says. “We haven’t had much chance to find out.”

If “Les Blancs” ultimately argues that any means, including violence, may be necessary to overthrow oppression, the argument isn’t a happy one. The play ends in fire and death and a howl of absolute anguish. Set in an invented African nation, it reflects on America, too. Tshembe has traveled in America, in the South, particularly. He has no admiration for what he calls “American apartheid.”

In 1970, that parallel terrified many Broadway critics. The Variety reviewer Hobe Morrison reduced the play’s message to “revolution and that ghetto slogan, ‘kill whitey.’” John Simon said that it works to “justify the slaughter of whites by blacks.” But Clayton Riley, a Black critic, argued that the play rather offers something of Hansberry herself, of a brilliant mind “struggling to make sense out of an insane situation, aware — way ahead of the rest of us — that there is no compromise with evil, there is only the fight for decency.”

That prescience that Riley identified persists, as does the moral clarity of Hansberry’s questions — questions that still don’t have answers. Watching “Les Blancs,” I wondered what Hansberry would have made of the upheavals of the present and about the play she might have written in response. We don’t have that play. We do have this one.

In more ordinary times, I would hope that a theater — BAM, say, or St. Ann’s Warehouse — would import Farber’s production. But international touring may not resume for years. Besides, “Les Blancs” is a work that’s rich enough and fluid enough to invite multiple interpretations. It’s time that America again took “Les Blancs,” a work that was always, at least in part, about America, and made it our own.