Technique could be ‘very powerful weapon’ in boosting crop yields as environmental crisis worsens

Modern agricultural methods mean around 40 per cent of all crops are currently lost to pests and diseases. But as the climate crisis worsens, the outlook is set to become even more grim.

When heatwaves strike, crops can be decimated, hitting human food supplies, as well as the plants grown to feed livestock and for biofuel used in vehicle engines.

Alongside drought, which high temperatures can exacerbate, plants’ defences are compromised by heat, leaving them prone to attacks by pathogens and insects.

Now, a team of scientists at US and Chinese institutions say they have identified the exact process which leads to faltering plant immunity as temperatures rise, and have worked out a way to stop this process and bolster plants’ defences during periods of heat.

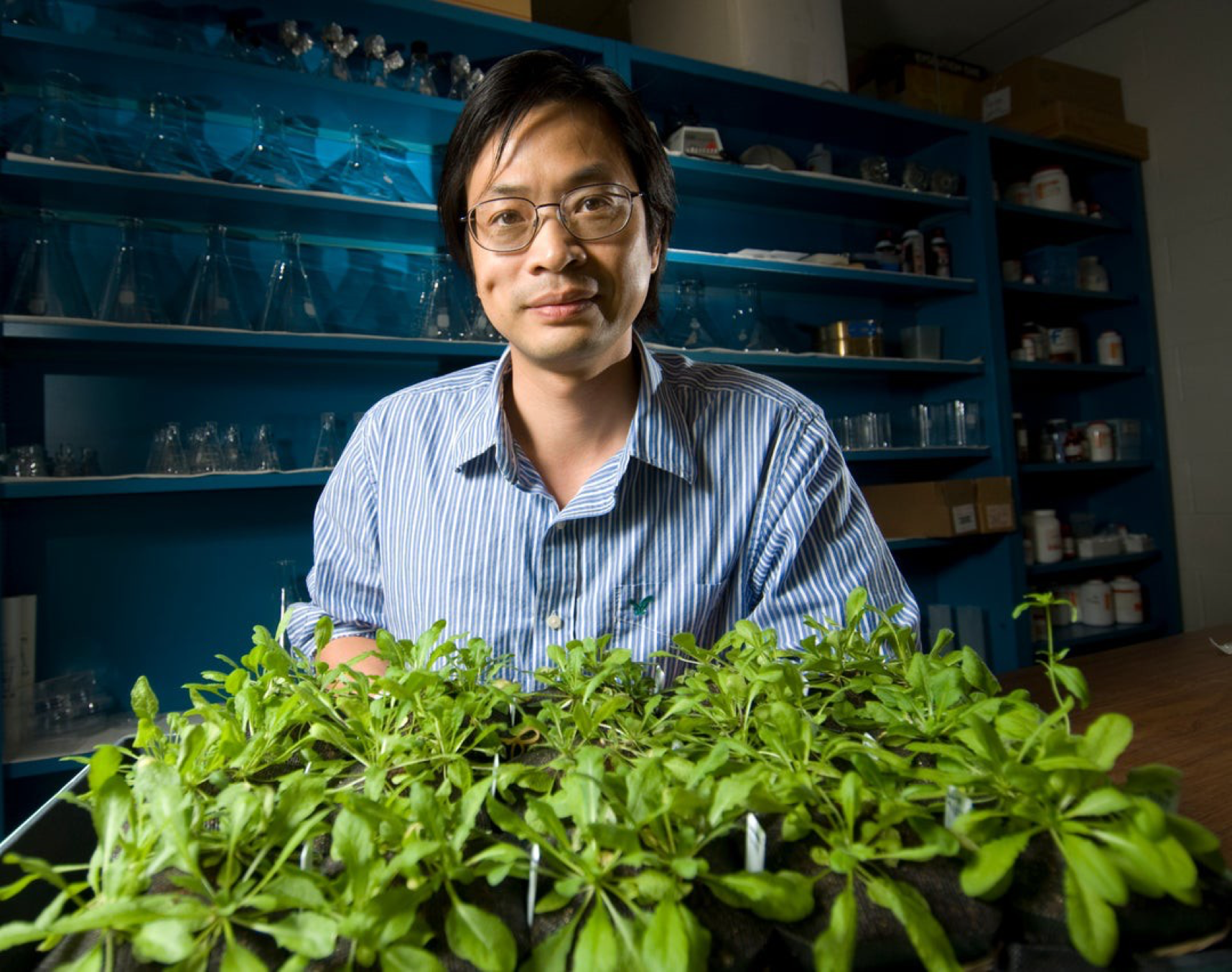

The researchers carried out tests on a plant known as thale cress, from the mustard family, which is widely used as a “lab rat” by plant scientists. If the findings are transferable to commonly grown crops, it could help maintain higher yields during extreme weather.

The research focuses on a defence hormone called salicylic acid. When plants come under attack from predators or diseases, the levels of salicylic acid rise by up to seven-fold. This hormone fires up the plant’s immune system and helps them fight off the attack.

However, over certain temperatures plants simply fail to ratchet up their salicylic acid levels, and as a result are unable to fend off pathogens or pests. This happens as a result from even brief heatwaves, the researcher said.

Sheng-Yang He, a biology professor at North Carolina’s Duke University who led the study, said: “Plants get a lot more infections at warm temperatures because their level of basal immunity is down.

“So we wanted to know, how do plants feel the heat? And can we actually fix it to make plants heat-resilient?”

During several years of growing plants at different temperatures, the team examined cells called phytochromes, which function as internal thermometers – helping plants sense warmer temperatures in the spring and activate growth and flowering. They tried exposing mutant plants in which the phytochromes were constantly active, yet even these plants shut down their immune responses when exposed to elevated temperatures.

So they changed tack and used “next-generation sequencing” to compare the plant’s genes at different temperatures.

It turned out that many of the genes that were suppressed at elevated temperatures were regulated by the same molecule, a gene called CBP60g.

“The CBP60g gene acts like a master switch that controls other genes,” the researchers said, “so anything that downregulates or ‘turns off’ CBP60g means lots of other genes are turned off, too. They don’t make the proteins that enable a plant cell to build up salicylic acid.”

They discovered that when heatwaves occur, the “cellular machinery” needed to start reading out the genetic instructions in the CBP60g gene does not assemble properly when it gets too hot. This means the plant’s immune system cannot do its job anymore.

To get around this problem, the team created mutant thale cress in which the CBP60g gene is constantly “switched on”, and were therefore able to keep their defence hormone levels up and bacteria at bay, even under heat stress.

When it comes to future food security, Professor He said the real test will be whether their strategy to protect immunity works in food crops as well.

Elevated temperatures have a similar detrimental effect on salicylic acid defences in crop plants such as tomato, rapeseed and rice.

The team said their follow-up experiments to maintain CBP60g gene activity in rapeseed were showing the same promising results.

“We were able to make the whole plant immune system [for thale cress] more robust at warm temperatures,” Professor He said.

“If this is true for crop plants as well, that’s a really big deal because then we have a very powerful weapon.”

The team, who also included scientists at Yale University, the University of California, Berkeley, and Tao Chen Huazhong Agricultural University in China, have filed a patent application based on their work.

There are growing concerns that patents on gene-editing could stifle the availability of important tools to tackle hunger around the world as the climate crisis affects crop yields, while also putting more power in the hands of big businesses which control the global food system.

The research is published in the journal Nature.