Scientists are inching one step closer toward redefining the length of a second.

To do that, they’re using atomic clocks.

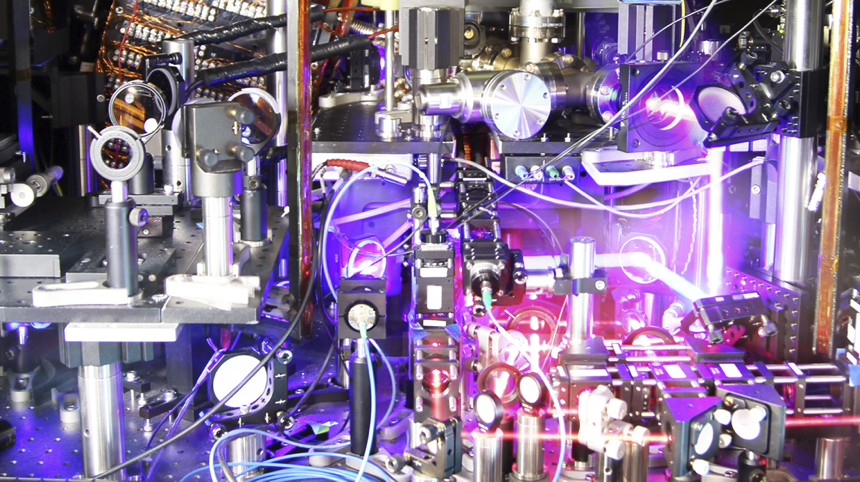

Atomic clocks, which look like a jumble of lasers and wires, work by tapping into the natural oscillation of atoms, with each atom “ticking” at a different speed.

Modern conveniences including cellphones, the Internet and GPS are all made possible through the ticking of atomic clocks.

“Every time you want to find your location on the planet, you’re asking what time it is from an atomic clock that sits in the satellite that is our GPS system,” Colin Kennedy, a physicist at the Boulder Atomic Clock Optical Network (BACON) Collaboration, tells NPR’s All Things Considered.

The worldwide standard atomic clocks have for decades been based on cesium atoms — which tick about 9 billion times per second.

But newer atomic clocks based on other elements tick much faster — meaning it’s possible to divide a second into tinier and tinier slices.

These newer atomic clocks are 100 times more accurate than the cesium clock. But it was important to compare them to each other — to “make sure that a clock built here in Boulder is the same as a clock built in Paris, as in London, as in Tokyo,” he says.

“Ultimately, the goal is to redefine the second in terms of a more accurate and precise standard, something that we can make more accurate and more precise measurements with,” Kennedy says.

That means having a clock that if set back billions of years to the beginning of the universe would only be off by a second, adds physicist Jun Ye, who was also involved in the collaboration.

As the scientists with BACON, which includes researchers from the University of Colorado Boulder and the National Institute of Standards and Technology, wrote in the science journal Naturelast week, they compared three next-generation atomic clocks that use different elements: aluminum, strontium and ytterbium.

The scientists shot a laser beam through the air in efforts to connect their clocks, which are housed in two separate laboratories in Boulder, Colo. They also used an optical fiber cable.

“It was a fun experiment for sure,” Ye tells NPR. “And it’s by all measures actually very safe, and very much out of the way for people’s daily life.”

What resulted is a more accurate comparison of these types of atomic clocks than ever before.

Ye says networks of clocks like this could also be used as super-sensitive sensors — to possibly detect a passing wave of dark matter, and to test Einstein’s theory of relativity.