I use the word “miracle” lightly, but really, 71 years ago I did experience a miracle, and here I am in your company today.

Setsuko Thurlow, speaks for the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons at a conference in Madrid on February 24. She has spent decades describing her experience as a survivor of the 1945 atomic bombing of Hiroshima. (Photo: David Benito/Getty Images)I would like to share my personal experience with you. I know many of you are experts, arms control specialists; and I’m sure you’re quite well informed and knowledgeable of all kinds of human conditions, including the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons. But I thought I would offer my personal and first-hand experience.

In 1945 I was a 13-year-old eighth grade student in the girls’ school, and on that very day, I was at the army headquarters. A group of about 30 girls had been recruited and trained to do the recording work of the top-secret information.

Can you imagine, a 13-year-old girl doing such important work? That shows how desperate Japan was.

I met the girls in front of the station before 8 o’clock; and at 8 o’clock, we were at the military headquarters, which was 1.8 kilometers from ground zero. I was on the second floor and started with a big assembly, and an officer gave us a pep talk.

This is the way you start proving your patriotism for emperor, that kind of thing. We said, “Yes sir, we will do our best.” When we said that, I saw the blaze of white flash in the window, and then I had the sensation of smoking up in the air.

When I regained consciousness in the total silence, I was trying to move my body. I couldn’t move it at all. I knew I was faced with death.

Then I started hearing whispering voices of the girls around me: “God, help me, mother help me. I’m here.” So, I knew I was surrounded by them, although I couldn’t see anybody in the darkness.

Then, suddenly, a strong male voice said, “Don’t give up. I’m trying to free you.” He kept shaking my left shoulder from behind and pushed me. We kept kicking, pushing; and you see, we’re finally coming to the door opening, get out that way, crawl, as quickly as possible.

By the time I came out of the building, it was on fire. That meant about 30 other girls who were with me in that same place were burning to death. But two other girls managed to come out, so three of us looked around.

Although that happened in the morning, it was very dark, dark as twilight, and I started seeing some moving black object approaching to me. They happened to be the streams of human beings slowly shuffling from the center part of the city to where I was.

They didn’t look like human beings. Their hair was standing straight up. Burned, blackness, swelling, bleeding. Parts of the bodies were missing. The skin and flesh were hanging from the bones. Some were carrying their own eyeballs, you know, they’re hanging from the eye socket.

They collapsed onto the ground, their stomach burst open with their intestines sticking out. The soldier said, “Well you girls, join that procession, escape to the nearby field.”

That’s what we did by carefully stepping over the dead bodies, injured bodies. It was a strange situation. Nobody was running and screaming for help. They just didn’t have that kind of strength left.

They were simply whispering, “Water please, water please.” Everybody was asking for water.

We girls were relatively lightly injured. So, by the time we got to the hillside, we went to a nearby stream and washed off the blood and dirt, and we took off our blouses and soaked them in the stream and dashed back to hold them over the mouths of the dying people.

You see, the place we escaped to was the military training ground, a huge place, about the size of two football fields. The place was packed with the dead and dying people.

I wanted to help, but everyone wanted water, but there were no cups and no buckets to carry the water. That’s why we resorted to that rather primitive way of so-called rescue operation. That was all we could do.

I looked around to see if there were any doctors around us, but I saw none of them in that huge place. That meant, tens of thousands of people in that place without medication, no medical attention, ointment.

Nothing was provided for them. Just a few drops of water from a wet cloth. That was the level of support, rescue operation you could offer.

We kept ourselves busy all day doing that. Of course, doctors and nurses were killed too. Just a small percentage of the medical professionals survived, but they were serving people somewhere else, not where I was.

So, we were three girls, together with hundreds of other people who escaped to the place. We just sat on the hillside and all night, we watched the Empire City burn, to see the moon from the massive scale of death and suffering we had witnessed.

I was mad, strongly, appropriately, emotionally. Something happened to my psyche. When we close off our psychic memory, in an ultimate situation like that, the cessation of the emotions takes place automatically. I’m glad of that because if we responded emotionally to every graphic sight I witnessed, I couldn’t have survived.

The day ended. Other people can tell about being near the rivers, full of floating dead bodies, and so on. But I didn’t see that then.

But I’ll tell you about the few people in my family, my friends, how they lost their lives. That will show you just how the bomb affected human beings.

I mentioned about 30 girls who were with me, but the rest of the students were at the city center. The city was trying to establish the facilities to be prepared for the air raid.

So, the seventh-grade and eighth-grade students from all the high schools were recruited, went to the center of the city. We were providing the minor labor.

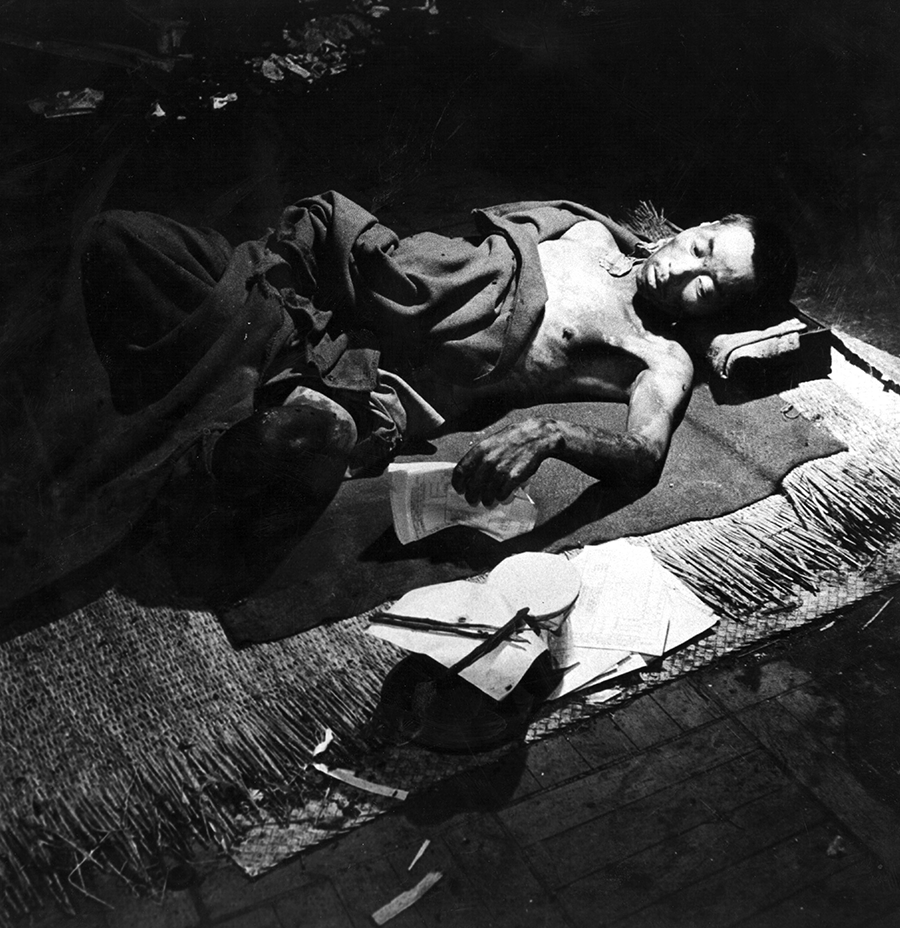

A victim of the Hiroshima atomic bomb is treated at a makeshift hospital in September 1945. Immediately after the bombing, Setsuko Thurlow sought to provide aid and comfort to wounded survivors. (Photo: Wayne Miller/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)Now, they were in the center right below the detonation of the bomb. So they are the ones who simply vaporized, melted, and carbonized. My sister-in-law was there with a student. She was one of the teachers supervising the students. We tried to locate her corpse, but we have never done so. On paper, she’s still missing, together with thousands of other students.

I understand there were several thousand students, 8,000 or so. They simply disappeared from the face of earth. The temperature of the blast, I understand, was about 4,000 degrees Celsius.

Another story I can tell is about my sister and her four-year-old child, who came back to the city the night before to visit us. Early in the morning, they were walking over the bridge to the medical clinic, and both of them were burned beyond recognition.

By the time I saw them the next day, their bodies were swollen two or three times larger than normal, and they too kept begging for water. When they died, the soldiers dug a hole and threw in the bodies, poured gasoline, and threw a lighted match.

With a bamboo stick, they kept turning the bodies. There I was, a 13-year-old girl, and I was standing emotionlessly just watching it.

That memory troubled me for many years. What kind of human being am I? My dear sister being treated like animal or an insect or whatever.

There was no human dignity associated with that kind of cremation. The fact that I didn’t really shed tears troubled me for many years. I felt guilt.

I could forgive myself after learning how our psyche automatically functions in situations like that. But, you know, it’s the image of this four-year-old child that is burned to my retina. It’s always there.

That image just guided me, and it’s the driving force for my activism. Because that child came to represent all the innocent children of the world without understanding what was happening to them. They agonized.

So that child is a special being, a special memory. If he were alive, he would be 75. It’s a sobering thought, but regardless of passage of time, he’s still a four-year-old child guiding me.

It was interesting, [President Barack] Obama made a lot of references about innocent children, how we need to protect each one of them, and I was weeping. I couldn’t help it.

Now, let me tell you another example of how the atomic bomb affected the human beings. We rejoiced to hear my favorite uncle and aunt survived. They were okay. They didn’t have any visible sign of injury.

Then several days later, we started hearing a different story. They got sick, very sick. So after my sister and my nephew died, my parents went over to my uncle’s place, started looking after them.

Their body started showing purple spots all over the body, and according to my mother, who cared for them until their death, their internal organs seemed to be rotting, dissolving, coming out as a thick black liquid until death.

Now, radiation works in many mysterious and random ways. Some people are killed immediately, some weeks later or months later, a year later. The horrible thing is, 71 years later, people are still dying from the effects of the radiation.

The hibakusha, the survivors, struggled to explain in the aftermath. It’s surviving in the unprecedented catastrophic aura and the unprecedented social, political chaos due to Japan’s defeat and the occupational forces’ strict control over us.

I finished university in Japan, and upon my graduation, I was offered a scholarship, so I came to your country. I came to Virginia, very close to this city.

That was 1954. The United States tested the biggest hydrogen bomb at the Bikini Atoll in the South Pacific that time, creating the kind of situation similar to the Hiroshima and Nagasaki experience.

All of Japan was up in arms with fury. It was not only Hiroshima, not only Nagasaki, now the Bikini Atoll. Well, the United States continued with the testing and actually using them.

That’s when all of Japan became fully aware of the nature of nuclear weapons development. Anyway, at that time, I left Japan, arrived in Virginia, and I was interviewed by the press.

I gave my honest opinion. I was fresh out of college and naive and believed in honesty. I told them what I thought: The United States nuclear policy was bad. It has to stop. Look at all the killings and damage to the environment in the Pacific. That has to stop, and all these kinds of thing I said.

The next day, I started receiving hate letters. “How dare you? Do you realize where you are? Who is giving the scholarship? Go home. Go back to Japan.” Just a few days after my arrival, I encountered this kind of situation, and I was horrified. It was quite a traumatic experience.

What am I going to do? I can’t go back, I just arrived. I can’t put a zipper over my mouth and pretend I never knew anything about Hiroshima bombing.

Would I be able to survive in North America? Well, I spent a week without going to the classroom. I just had to be alone and do my soul-searching.

It was a painful and lonely time in a new country. I hardly knew anybody, and I had to deal with this issue. I’m happy to say that I came out of that traumatic experience with more determination and a stronger conviction.

If I don’t speak out, who will? I actually experienced it. I saw it. It’s my moral responsibility. So, I have my experience to warn the world. We’ve seen this is just the beginning of the nuclear arms race. I just have to warn the world.

Adapted from remarks delivered to the Arms Control Association on June 6, 2016, shortly after U.S. President Barack Obama’s visit to Hiroshima. At the age of 13, Setsuko Thurlow survived the atomic bombing in Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. She has since worked to tell the story of the survivors, the hibakusha. She was the Arms Control Association’s 2015 Arms Control Person of the Year, a leading champion within the International Campaign for the Abolition of Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) for the negotiation of the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, and for that was a co-recipient of the 2017 Nobel Prize for Peace.