Parts of Spain this summer are experiencing the worst drought the country has seen in 1,200 years, as extreme heat and drought grip much of Europe.

The drought’s severity can be partially attributed to climate change, a study published in July in Nature Geoscience found, thanks to an increase in high-pressure systems in the winter that help create dry conditions in the summer. The dry weather is seriously affecting the country’s water supply: Reservoir levels in August were sitting at just 36% of their capacity, the government said last month, way below the 10-year average of 60%.

This newsletter comes from the future.

Here’s what the drought looks like in Spain right now—and the implications for key exports like olive oil.

Olive Oil at Risk

The lack of water is taking a toll on one of the country’s most iconic products. Spain is the world’s largest producer of olive oil: It produced more than 1.1 million gallons of olive oil in 2019, handily beating out the second-place country, Greece, which produced a little over 336,000 gallons that same year.

But the BBC reported that the Spanish crop is already a third less productive than usual, and analysts told CNN that the olive harvest, which begins in October, could suffer losses between 33% and 38%.

‘Too Dry’ for Olives

“The drought is too significant. It’s simply too dry,” analyst Kyle Holland told CNN. “Some trees are producing very little fruit, some trees are producing no fruit at all. This only happens when soil moisture levels are critically low.”

Spain’s Thirsty Agriculture

Irrigation for crops like olives, strawberries, and avocados takes up around 80% of Spain’s water resources. The drought is forcing the country to rethink its huge allocation of water and reliance on irrigation for agriculture.

“We cannot be Europe’s vegetable garden” while “there are water shortages for the inhabitants,” Julia Martinez, biologist and director of the FNCA Water Conservation Foundation, told AFP.

Punishing Heat

The extreme heat has been especially tough on the olive crop. The heat began spiking in Spain in May, when temperatures soared well above average in the first heat wave of the season near the end of the month. May is a crucial time for olive growth—flowers begin to bloom in May—and the intense heat then took a toll on the rest of the growing season.

Fires and Deadly Heatwaves

July was Spain’s hottest month in more than 60 years. Wildfires also charged through several provinces this summer, burning more than 476,000 acres in the first seven months of the year alone. That’s about double the size of Singapore and makes 2022 the worst wildfire year in the past decade, with months left to go. Officials say that more than 500 people died across the country in a heatwave that gripped Spain in July and saw temperatures as high as 45 degrees Celsius (113 degrees Fahrenheit).

Water Levels Dangerously Low

In Axarquía, a region of Andalusia, the low water levels in the local reservoir and lack of rain may mean that by October, there could be no water left available in the reservoir for irrigation, Spanish newspaper Sur reported. The La Viñuela reservoir, the largest reservoir in the region, serves 180,000 people in 14 municipalities; the reservoir sat at just 13% capacity in August. Some farmers have turned to recycled water from the local sewage plant to use on their crops, Sur reported.

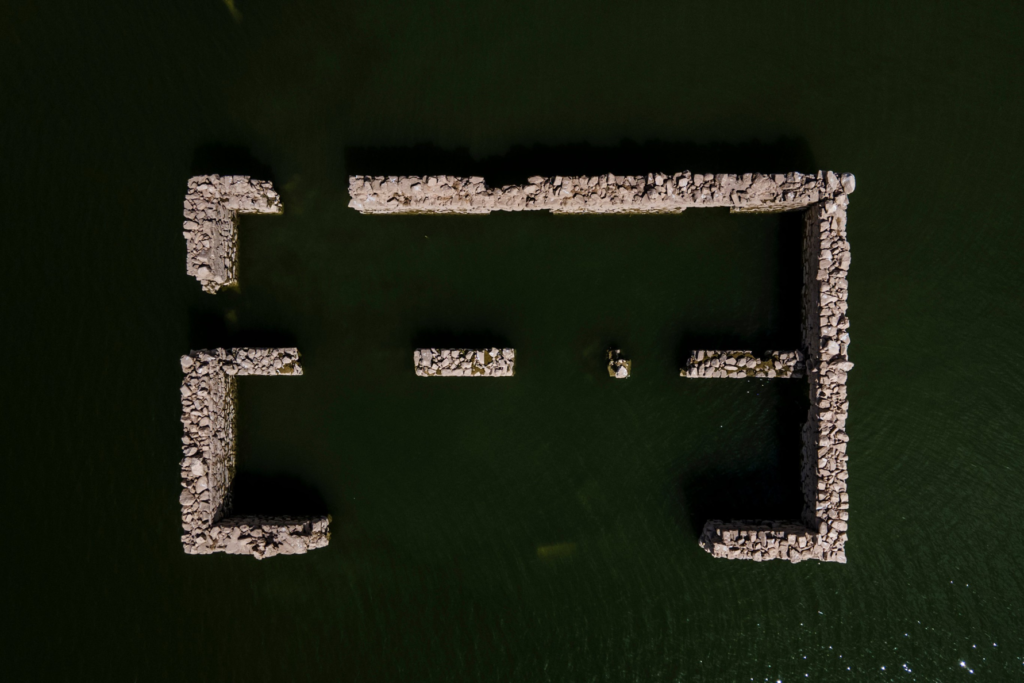

Historical Sites Exposed

Across the world this summer, low water levels have exposed previously sunken secrets, from bodies to shipwrecks, and Spain is no exception. Dozens of buildings and historic sites have appeared in shrinking reservoirs across the country this year, including remains of bathhouses, churches, a Stonehenge-like archaeological site, and even an entire abandoned village.

This newsletter comes from the future.