History shows that holding former leaders to account pays off—if it’s done in the right way.

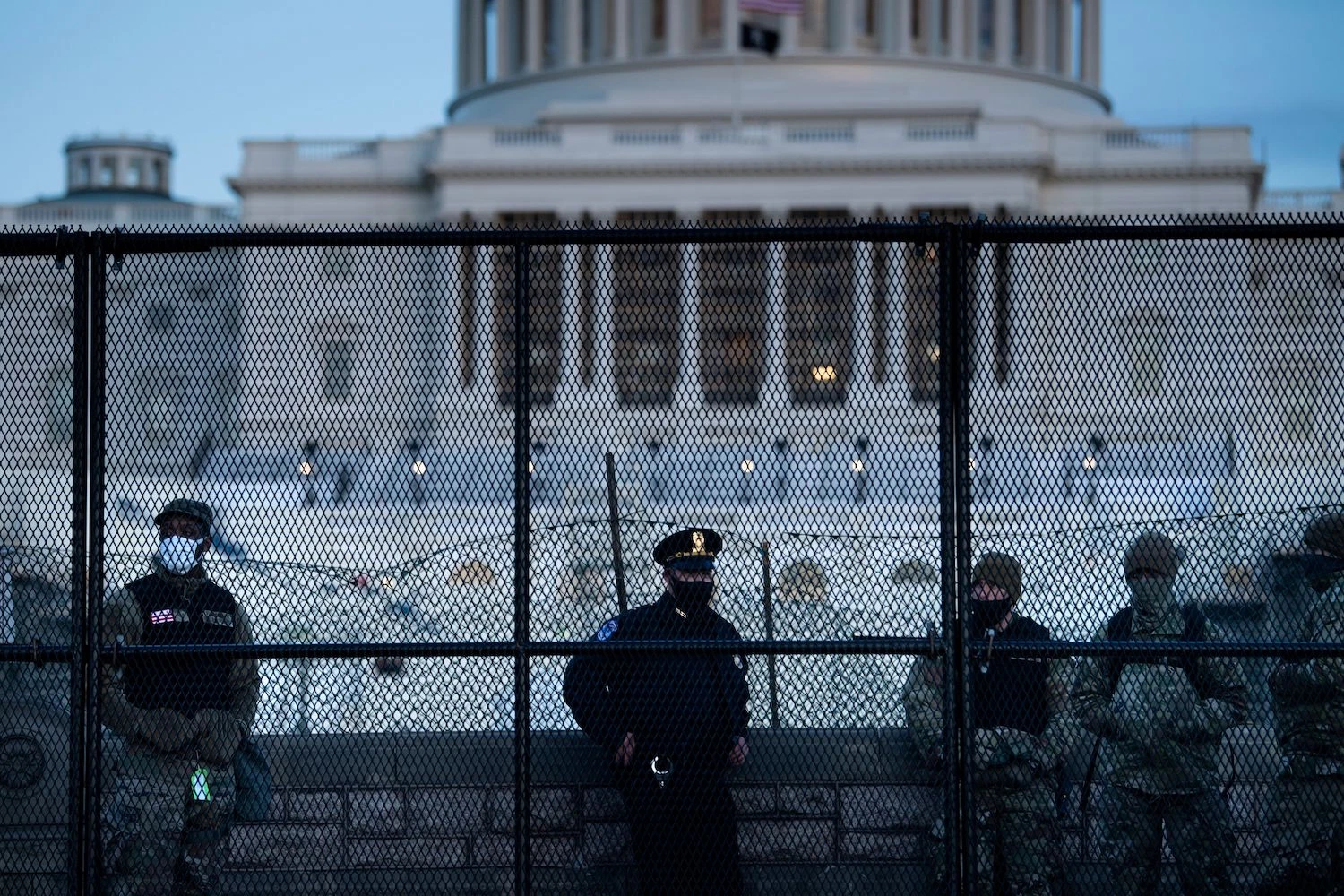

For almost as long as Donald Trump has been president, Americans have been debating whether or not he should be prosecuted for the various crimes he may have committed in office. That debate intensified on Saturday, when Trump called Georgia’s secretary of state, Brad Raffensperger, and appeared to threaten him unless he came up with 11,000 more votes for the president. Then came Wednesday’s mass assault on Capitol Hill, which Trump did so much to incite.

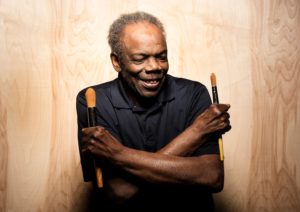

Advocates of prosecuting or impeaching Trump make strong arguments, but so do those who think the country should just move on. That makes choosing the right answer difficult—especially because neither side has used much data to make a case. But the evidence is out there. To understand what the history of past attempts to prosecute heads of state can teach us, Jonathan Tepperman, Foreign Policy’s editor-at-large, spoke on Wednesday with Pablo de Greiff, who from 2012 to 2018 served as the first U.N. special rapporteur on the promotion of truth, justice, reparation, and guarantees of non-recurrence. Their conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Jonathan Tepperman: The strongest and most basic argument made by advocates for prosecution is that the United States is a country of laws and must do everything it can to demonstrate that no one is above those laws. Opponents of prosecution argue that a trial could turn Trump into a martyr, further energize his base, help raise even more money, and encourage him to run in 2024—so the best thing for the country might be to just turn the page.

What does the historical record tell us about whether or not prosecutions work? And what metrics should we use to judge whether these cases have been good or bad for the countries involved?

Pablo de Greiff: To start with, it makes a huge difference what you would prosecute a former leader for. It’s not an abstract debate about impunity versus prosecution.

It’s not an abstract debate about impunity versus prosecution.

It should be a precise debate about specific charges and what consequences would follow from prosecuting them.

As for how to measure the effectiveness of prosecutions, when it comes to issues like the rule of law, metrics are very difficult to come by. It’s hard to determine whether an individual case has an impact on rule-breaking in the future.

Now, I do think that there is a case to be made for the importance of making sure that legal systems signal that no one is above the law. Therefore, for instance, Guatemala’s prosecution of its former president, Efraín Ríos Montt, was very important because all Guatemalans got to see him being forced to comply with a court of law and a judge who repeatedly told him, “No, it’s not your turn to speak. No, you cannot address me this way. No, this is not something that you can say.” Scenes like that alone were extraordinarily important for a country like Guatemala.

In deciding whether to prosecute Trump, I think two major considerations should be kept in mind. First, there has been a great erosion of the rule of law in the United States, which for me is manifested mainly in the politicization of the judicial system. I don’t know if you have noticed, but it’s become common for news reports, when referring to a judge, to specify which president appointed that judge. I’ve been in this country for almost 40 years, and that’s a noticeable change; it didn’t happen much before.

I also think that, particularly over the last four years, there have been a lot of public attempts to undermine judicial decision-making, which was once seen as almost sacred here. I mention all this because having a reliable judicial system is important when you are advocating prosecutions, and I think that the state of the judicial system in this country has declined tremendously. The erosion is both systematic and involves the way the people view the judiciary.

JT: Does that change in perception increase the importance of prosecuting Trump, since it would help fight back against the erosion of these norms?