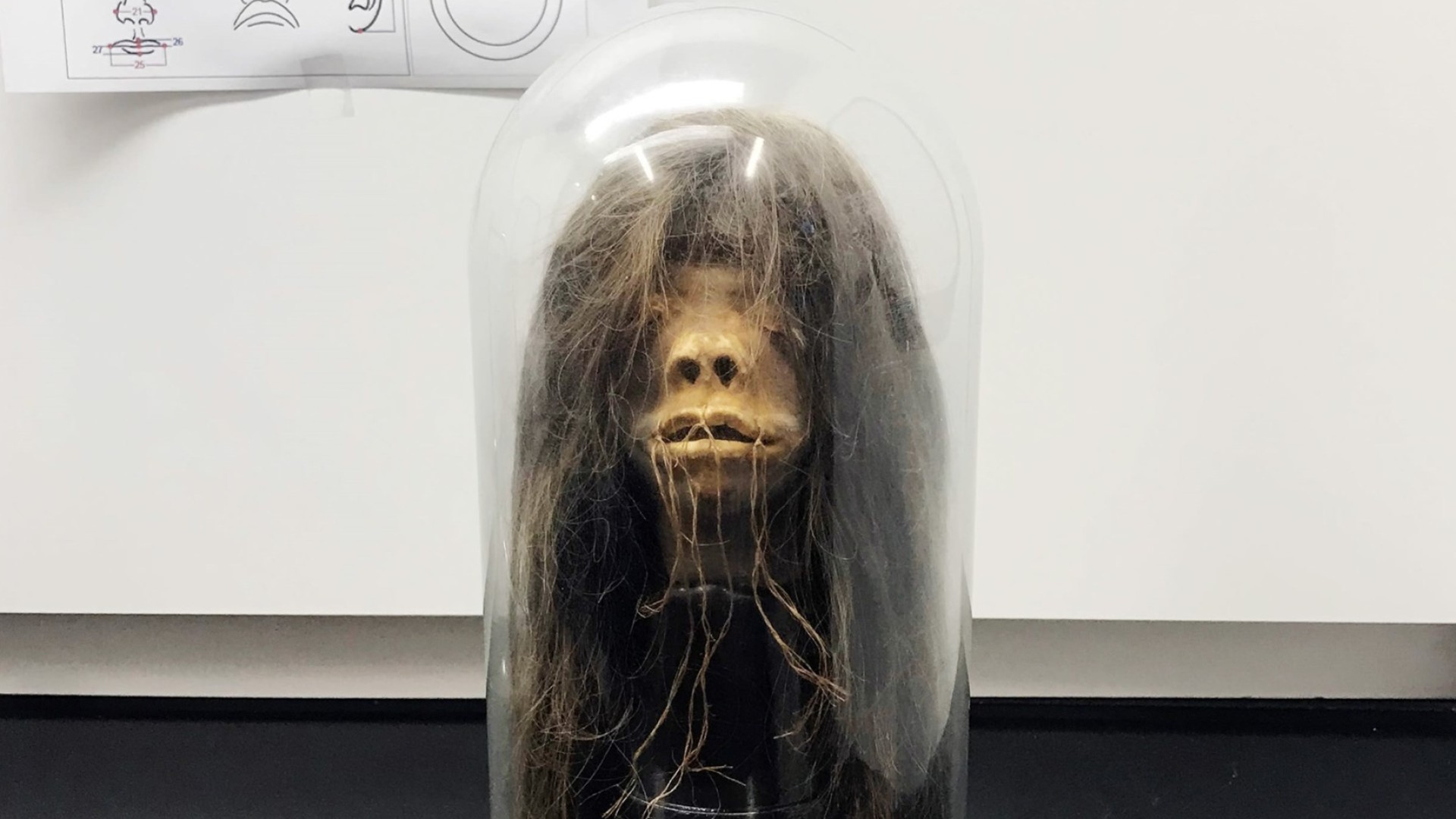

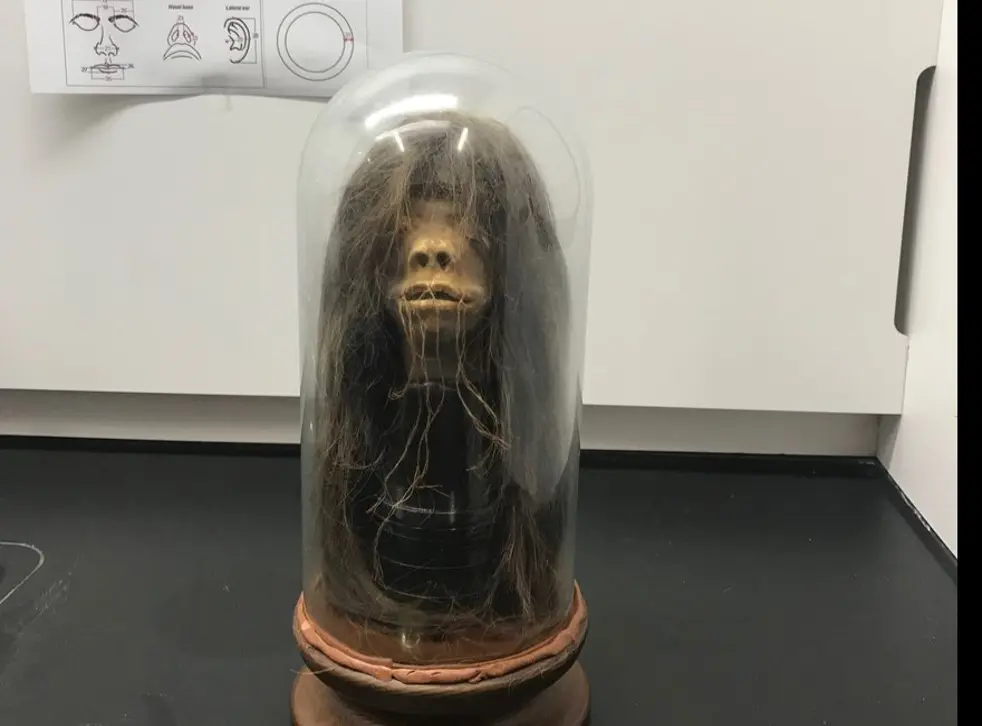

Researchers say their tests show the object is what it was supposed to be — a genuine shrunken human head — opening the door to its return to Ecuador.

A grim artifact that had been placed on display for decades in a Georgia university has been authenticated as a human head taken from a slain enemy by an Amazonian warrior almost a century ago — and is now on its way back to where it came from.

Researchers at Mercer University in Macon say their tests show the shrunken head – called a tsantsa in Amazonian languages – is a genuine shrunken head made in a laborious ceremony of removing its skull and flesh, stitching shut its eyes and mouth, boiling it and then filling it with hot sand and stones.

In 2019, Mercer University repatriated the verified tsantsa to the Ecuadorian Consulate in Atlanta. It’s not clear if it’s yet been returned to Ecuador from there, but the researchers said they hope it will ultimately be part of a collection, perhaps at a museum, where it will be treated properly.

“We wanted it to be viewed by people who could appreciate it in an appropriate context,” said Mercer University chemist Adam Kiefer, a co-author of a study of the shrunken head published Monday in the journal Heritage Science.

“This is not an oddity – this is somebody’s body, this is somebody’s culture, and it’s not ours,” he said. “So from our perspective, repatriation was essential, and we were very lucky that our university supported this endeavor.”

Shrunken heads were popular curios and keepsakes in some parts of the Western world in the 19th century, and many fakes were made to meet the demand – some of which were illicitly created from bodies taken from cemeteries and morgues. That led to justifiable concerns that the tsantsa at Mercer University may have also been fake.

Kiefer and his colleagues at Mercer University, biologist Craig Byron and biomedical engineer Joanna Thomas, were tasked with verifying that the shrunken head was genuine after academics decided it could be of cultural importance and Ecuador’s government asked if it could be authenticated.

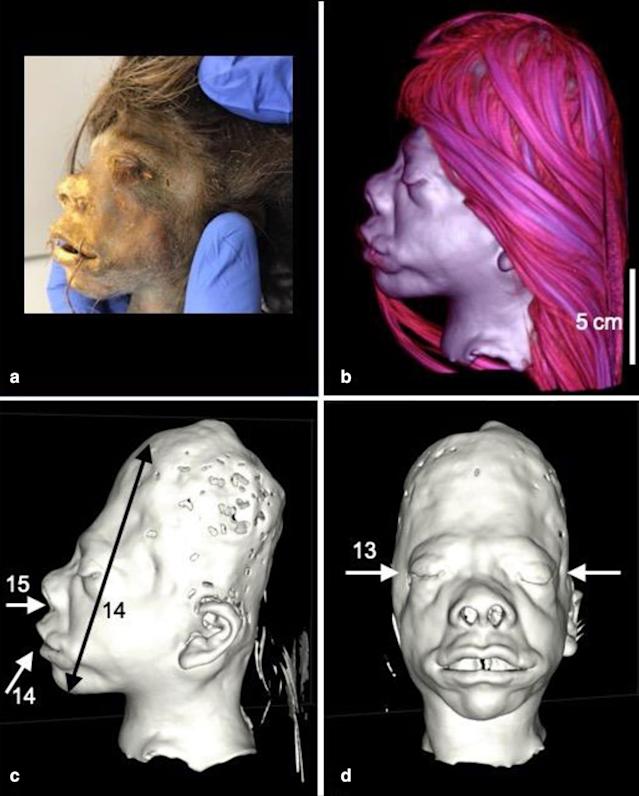

The researchers studied it with a variety of techniques, including computerized tomography (CT) scans, which allowed them to reconstruct a three-dimensional model of the tsantsa both with and without its long hair. Thomas explained that the CT scans verified that the head of the tsantsa underneath its hair had been cut open to remove the skull, then stitched up again as part of the ceremonial process that created it. The CT scans were also used to create a three-dimensional model to take its place in the university’s collection.

Their tests showed the shrunken head met 30 of the 32 criteria scientifically accepted for verifying authentic tsantsas, including the tiny hairs visible on its skin and in its nostrils, and its distinctive three-tiered hairstyle, which was characteristic of the peoples who then lived in the Ecuadorian Amazon region where it was from, Kiefer said.

The tsantsa at Mercer became part of the university’s collection after the death in 2016 of a member of the faculty, biologist Jim Harrison.

He’d acquired it during a trip into Ecuador’s remote Amazon region in 1942 while serving in the U.S. Air Force during World War II.

Harrison wrote in a memoir that he had traded with local people for the tsantsa. “It was Indiana Jones,” Kiefer said. “When this was collected, science was different, everything was new… but almost 80 years later, we recognize its cultural importance, along with the science.”

It’s thought the ceremonial process of making tsantsas may have originated as a way of overcoming a tradition of blood feuds among some peoples of the Amazon jungle; it seems to have been intended to trap the spirit of the slain warrior within the shrunken head so its supernatural power could be transferred to the community of the victor.

Curiously, Harrison’s tsantsa also appeared as a movie prop in the 1979 John Huston film “Wise Blood,” a version of a novel by the writer Flannery O’Connor, who had lived near Macon. It was glued onto a prop body for the movie, and the damage that was caused could be seen by the researchers.

Universities and museums now often try to repatriate many of the human remains that were once on display in archaeological and anthropological collections.

In the United States, the Smithsonian Institution has been repatriating human remains and other culturally important objects since the 1980s, particularly to Native American communities. It has now repatriated more than 6,000 objects, including sending several tsantsas in 1999 to representatives of the indigenous Shuar people in Ecuador and Peru.

Last year, the Pitt Rivers Museum at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom removed a display of tsantsas that had been morbidly popular for decades.

“Visitors often referred to them as gruesome, or disgusting, or a freak show, or gory,” Laura Van Broekhoven, the museum’s director, said. “People were not understanding the more cultural meaning of the tsantsas… so we were not doing a very good job of how we were curating the display.”

The museum has now been negotiating for four years with South American universities and indigenous groups to repatriate the tsantsas; any human remains and cultural objects acquired in the future will be dealt with under strict regulations that the university has now adopted, she said.

“We have to take things case by case,” she said. “It’s often a long process.”