To mollify parents and obey new state laws, teachers are cutting all sorts of lessons

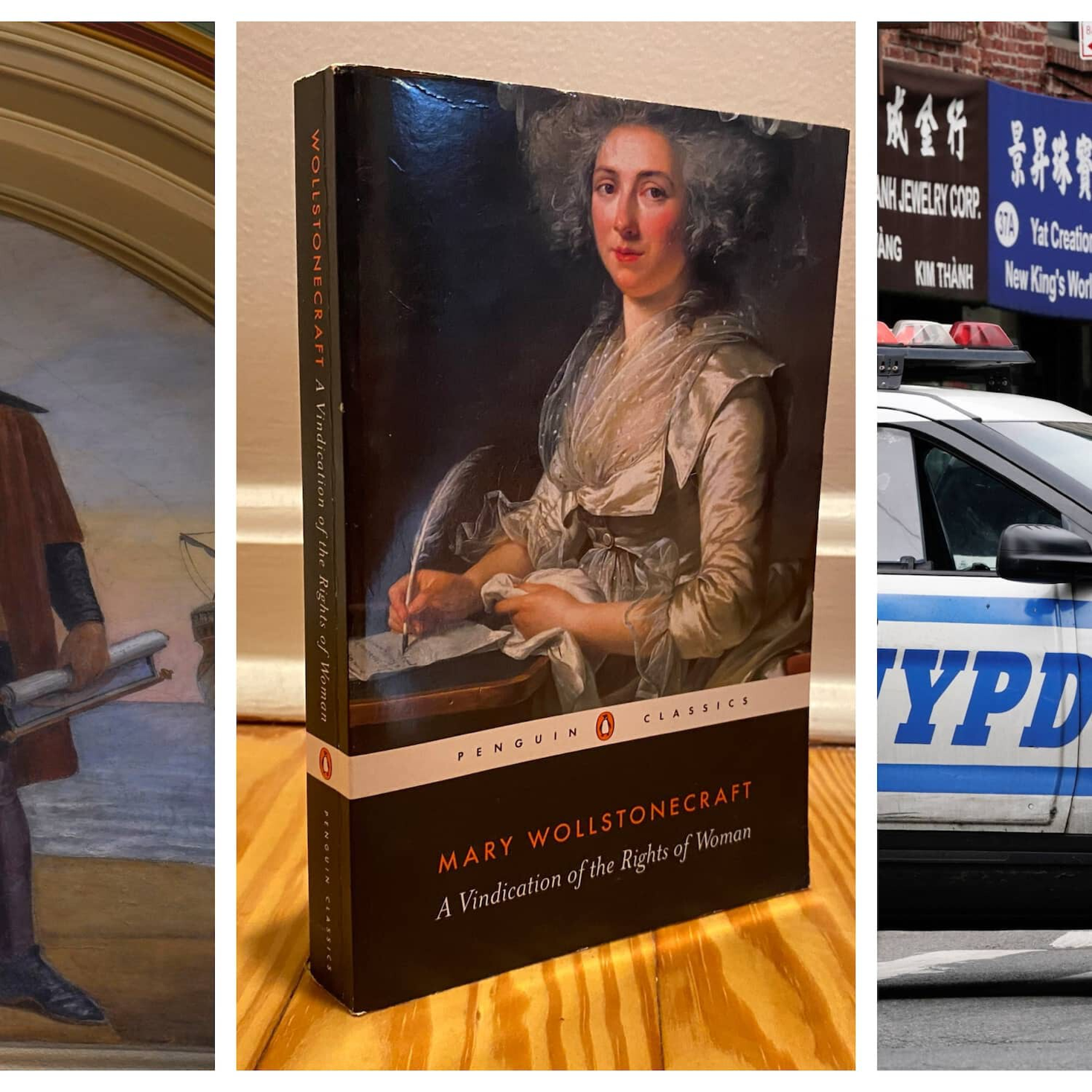

Excerpts from Mary Wollstonecraft’s “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.” Passages from Christopher Columbus’s journal describing his brutal treatment of Indigenous peoples. A data set on New York police’s use of force, analyzed by race.

These are among the items teachers have nixed from their lesson plans this school year and last, facing pressure from parents worried about political indoctrination, administrators wary of controversy, and a spate of new state laws restricting education on race, gender and LGBTQ issues.

“I felt very bleak,” said Lisa Childers, an Arkansas teacher who was forced by an assistant principal, for reasons never stated, into yanking Wollstonecraft’s famous 1792 polemic from her high school English class in 2021.

The quiet censorship comes as debates over whether and how to instruct children about race, racism, U.S. history, gender identity and sexuality inflame politics and consume the nation. These fights, which have already generated at least 64 state laws reshaping what children can learn and do at school, are likely to intensify ahead of the 2024 presidential election. At the same time, an ascendant parents’ rights movement born of the pandemic is seeking — and winning — greater control over how schools select, evaluate and offer children access to both classroom lessons and library books.

In response, teachers are changing how they teach.

A study published by the Rand Corp. in January found that nearly one-quarter of a nationally representative sample of 8,000 English, math and science teachers reported revising their instructional materials to limit or eliminate discussions of race and gender. Educators most commonly blamed parents and families for the shift, per the Rand study.

The Washington Post asked teachers across the country about how and why they are changing the materials, concepts and lessons they use in the classroom, garnering responses from dozens of educators in 20 different states.

Here are six things some teachers aren’t teaching anymore.

1. ‘Slavery was wrong’

Greg Wickenkamp began reevaluating how he teaches eighth-grade social studies in June 2021, when a new Iowa law barred educators from teaching “that the United States of America and the state of Iowa are fundamentally or systemically racist or sexist.”

Wickenkamp did not understand what this legislation, which he felt was vaguely worded, meant for his pedagogy. Could he still use the youth edition of “An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States”? Should he stay away from Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi’s “Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You,” especially as Kendi came under attack from conservative politicians?

That fall, Wickenkamp repeatedly sought clarification from the Fairfield Community School District about what he could say in class, according to emails obtained by The Post. He sent detailed lists of what he was teaching and what he planned to teach and asked for formal approval, drawing little response. At the same time, Wickenkamp was fielding unhappy emails and social media posts from parents who disliked his enforcement of the district’s masking policy and his use of Reynolds and Kendi’s text. A local politician alleged Wickenkamp was teaching children critical race theory, an academic framework that explores systemic racism in the United States and a term that has become conservatives’ catchall for instruction about race they view as politically motivated.

Finally, on Feb. 8, 2022, at 4:05 p.m., Wickenkamp scored a Zoom meeting with Superintendent Laurie Noll. He asked the question he felt lay at the heart of critiques of his curriculum. “Knowing that I should stick to the facts, and knowing that to say, ‘Slavery was wrong,’ that’s not a fact, that’s a stance,” Wickenkamp said, “is it acceptable for me to teach students that slavery was wrong?”

Noll nodded her head, affirming that saying slavery is wrong counts as a “stance.”

“We had people that were slaves within our state,” Noll said, according to a video of the meeting obtained by The Post. “We’re not supposed to say to [students], ‘How does that make you feel?’ We can’t — or, ‘Does that make you feel bad?’ We’re not to do that part of it.”

She continued: “To say, ‘Is slavery wrong’? I really need to delve into it to see is that part of what we can or cannot say. And I don’t know that, Greg, because I just don’t have that. So I need to know more on that side.”

As Wickenkamp raised his eyebrows and pursed his lips, she added, “I’m sorry, on that part.”

Wickenkamp left the Zoom call. At the close of the year, he left the teaching profession.

Contacted for comment, Noll wrote in a statement that “the district provided support to Greg with content through a neighboring school district social studies department head.” She did not answer a question asking whether she thinks teachers should be permitted to tell children slavery is wrong.

2. Christopher Columbus’s journal

For 14 years, a North Carolina social studies teacher taught excerpts of Christopher Columbus’s journal without incident. The point was to show how Columbus’s marriage of enslavement with his quest for profit helped shape the world we live in today.

The teacher, who spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of harassment, directed children to the first chapter of Howard Zinn’s “A People’s History of the United States,” titled “Columbus, the Indians, and Human Progress.” Throughout the chapter, students encountered paragraphs taken from the explorer’s journal in which Columbus delineated his views of, and interactions with, the Native peoples of America.

“As soon as I arrived in the Indies, on the first Island which I found, I took some of the natives by force,” Columbus wrote in October 1492, in a slice of the journal quoted by Zinn. “They would make fine servants. … With fifty men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want,” he also wrote.

But last school year, when the North Carolina teacher attempted to give this lesson to her sophomore honors world history class, a parent wrote an email complaining that her White son had been made to feel guilty.

The teacher recalled replying by asking, “Why would your child feel guilty about what Columbus did to the Arawak?” The parents of the student escalated the issue to human resources, the teacher said, spurring an administrator to warn she needed to stop “pushing my agenda — telling me that having my children learn the truth about Columbus was biased.” Soon after, she said, New Hanover County Schools placed an admonitory letter in the teacher’s file and ordered her to halt the lesson on Columbus.

Asked about the teacher’s allegations, New Hanover schools media relations manager Russell Clark wrote in an emailed statement that the district “cannot comment on individual personnel matters due to privacy laws,” but that any “disciplinary action taken by our district is done in accordance with our policies and state and federal laws.”

To fill the time left over from cutting short her unit on Columbus, the teacher gave children extended versions of her usual lessons on the French and American revolutions, she said.At the end of the year, frustrated and tired, she switched to a different school, where she was able to resume teaching the chapter by Zinn, including snatches of Columbus’s journal, she said.

But she still thinks about her former world history students.

“They missed the truth about exploration, they missed the whole lesson on colonization,” the teacher said. “They were really wanting to learn about Columbus. And what Cortez does, too.”

3. A data set on police use of force

A self-described nerd, a Northern Virginia teacher has always used math to explain the world around her. The woman, who spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of professional consequences, became a statistics teacher in Loudoun County Public Schools because she wanted to imbue children with that same love of math.

Last academic year, the teacher’s statistics class was diverse along racial lines, she said. Partly in hopes of appealing to her students of color but mostly because she wanted young people to know that math can be used to reveal how society works, she taught a lesson built around a data set exploring the outcomes of the New York Police Department’s stop-and-frisk program.

Analyzing the findings shows that citizens of color saw higher rates of police use of force, she told students.

“The whole purpose of that lesson was to drive home the point, ‘Okay, there is an association’ — but that we can’t necessarily conclude race is the cause of the difference,” the teacher said in an interview. “Association is not causation.”

She got no complaints from students or parents, she said. But at a mandatory professional development session the following summer, administrators warned that Virginia teachers — especially those in Loudoun County — were “under a microscope right now,” the teacher said. Staffers understood the comment, she said, as a reference to Republican Gov. Glenn Youngkin’s first-day executive order limiting education on race and “divisive concepts,” the tip line he set up allowing parents to report teachers and his intense scrutiny of the Loudoun district for its handling of two student sexual assaults.

The teacher asked higher-ups if she should stop teaching her lesson on the police use of force. She was told yes, because “it might make children uncomfortable” due to their race or if their parents are police officers, the teacher recalled.

Asked about the teacher’s account, Loudoun schools spokesman Dan Adams wrote in an emailed statement that the district remains “committed to maintaining an inclusive, safe, caring and rigorous learning environment.”

The most popular and interesting stories of the day to keep you in the know. In your inbox, every day.

The teacher has not taught the data set since. Without bothering to ask, she has also stopped discussing another well-known, peer-reviewed 2003 study that found higher callback rates for job applicants with traditionally White, vs. Black, names, which she once relied on to explain the concept of a statistically significant difference.

4. ‘A Vindication of the Rights of Woman’

In Arkansas last school year, 12th-grade English teacher Lisa Childers was struggling to interest her students in Tara Westover’s “Educated,” a memoir about growing up in a survivalist Mormon family from a splinter sect that saw little point in educating women.

But she saw a glimmer of curiosity from a handful of female students intrigued by Westover’s references to Mary Wollstonecraft, the 18th-century British philosopher and writer best known for her passionate argument for women’s equality, “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.”

Childers decided to suggest six passages of optional reading from the text. “Men considering females rather as women than human creatures,” Wollstonecraft wrote in one, “have been more anxious to make them alluring mistresses and affectionate wives and rational mothers; and the understanding of the sex has been … hobbled.”

Childers said she wanted female students to know that women had struggled to learn for centuries.

But on Jan. 18, 2022, the assistant principal at Bryant High School, apparently alerted to the Wollstonecraft assignment after reviewing Childers’s syllabus online, sent an email with the heading: “Questions about a document (please respond).”

The assistant principal wrote in the email, a copy of which was reviewed by The Post, that she had “a few questions” about Wollstonecraft’s essay: “What is the purpose of using it?” “How is it connected to what you are doing?” “Is it connected by skills?” “Is it connected by theme?”

The exchange spawned a lengthy back-and-forth over the next two weeks in which Childers sought to defend the assignment. She emphasized it was optional — but gave up when the assistant principal kept peppering her with questions as to why it was necessary.

Asked about Childers’s account, Devin Sherrill, director of communications for Bryant Public Schools, wrote in a two-page statement that Childers did not supply a “requested lesson plan to adequately justify including Wollstonecraft’s work as a part of her lesson.” “bring in articles of empathy and compassion rather than something that could negatively trigger our students.” In 2021, Bryant Public Schools overhauled its middle and high school English curriculums to eliminate books including Anne Frank’s “The Diary of a Young Girl,” with officials citing a need for more rigorous texts and tales that were not “overly dark and heavy.”

Asked about Childers’s account, Devin Sherrill, director of communication for Bryant Public Schools, wrote in a two-page statement that Childers did not supply a “requested lesson plan to adequately justify including Wollstonecraft’s work as a part of her lesson.” Sherrill wrote that Wollstonecraft’s text is not part of the district’s “curriculum map” and that Childers failed to show how “learning target(s) would be achieved” by assigning students “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.”

Childers said her class finished “Educated” without enthusiasm. The incident, she said, felt like a chilling repeat of censorship that occurs in the memoir.

“We weren’t even allowed to read the things Tara Westover is so pleased to be reading,” Childers said, “when she finally goes to college.”

5. ‘The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn’ and ‘Of Mice and Men’

Across two decades working in education, one Missouri English teacher said she received two complaints from parents objecting to Mark Twain’s “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.” As best she can recall, both complaints came from Black parents upset by the use of the n-word.

Sensitive to these concerns, the teacher was careful in how she taught the novel, which she believes is important reading because it grants children a glimpse into lives far different from their own.

“We would have a conversation with the kids about trying to understand why the word was used so frequently in the book — and we weren’t reading [the n-word] out loud, we would skip over,” she said. “We would also talk about how this showed the view of minorities during that time.”

But over the past three years, White parents began lodging complaints against “Huck Finn” in the teacher’s largely White and conservative town, she said. The teacher spoke on the condition of anonymity because her district forbids unsanctioned interviews with the news media.

The teacher said she received five complaints from White parents objecting to the n-word. She said several of her colleagues in the Wentzville School District reported similar objections.

In the 2021-2022 school year, right before she was slated to start teaching “Huckleberry Finn,” the teacher convened with colleagues at her high school. They discussed how parents in the district had begun sharing details of teacher behavior they disliked on social media, sometimes naming the offending educators.

The teachers decided to cut “Huckleberry Finn.” Also nixed was John Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men,” which had drawn similar objections over its profane language — again from White parents.

“We didn’t wait for complaints,” the teacher said.

The teacher said her administrators stayed out of it, content so long as the educators “did not cause problems.” Officials neither requested nor sanctioned nor questioned the books’ removal, she said. District chief communications officer Brynne Cramer wrote in a statement that “our educators are empowered to determine which texts best meet the needs of their learners,” adding that “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” and “Of Mice and Men” are both “available for staff to incorporate” into lessons.

In place of the two books, the teacher sent students a list of dystopian and science fiction novels, allowing them to choose whichever text appealed to them most and read it in small groups. She figured books in those genres were least likely to cause controversy.

But she thinks her students have lost out.

“When you can’t have conversations about class and race … it makes it more difficult for children to understand why people try to fight for equality,” she said. “You’re doing them a disservice.”

6. A Library of Congress video of a ‘cakewalk’

Rebecca Fensholt, a teacher at a North Carolina high school, spent weeks developing a three-day unit on “identity power and subversion” for her semester-long social studies class. Students learned how racial, ethnic, sexual and gender identities can be wielded to uphold or undermine those in power.

One part of the lesson, which Fensholt taught for three years with no problems, involved showing videos of “cakewalks,” dances that Black Americans began performing in the antebellum era partly to mock the formal dances held by their White, wealthy enslavers. Fensholt played an old Library of Congress video of a cakewalk, in which five Black men and women clad in posh period outfits dance for 41 seconds in a circle.

Fensholt also assigned a prompt that, she said, usually led to thoughtful discussions: “When is imitation subversion, and when is it emulation?”

But things changed this fall, when Fensholt decided to pair the video with an essay by bell hooks — “Is Paris Burning?” — in which the Black feminist and social critic dissects drag ball culture in 1980s-era New York.

Fensholt said she soon received a flurry of emails from four different parents contending broadly that the cakewalk video and the bell hooks text were irrelevant to social studies. One parent accused her, in a profanity-laced message that also promised to report her to the district, of indoctrinating students, she said.

Fensholt devoted hours to replying to each parent, explaining and defending her lesson in emails she checked repeatedly for tone. She also contacted Durham Public Schools officials, meeting with building administrators, an instructional coach and a teacher who serves as her mentor. Overall, she felt she got insufficient support from the district, she said. And the parent complaints just kept coming.

Reached for comment, district communications specialist Crystal Roberts wrote in a statement that “Durham Public Schools is in the process of gathering information regarding the incident cited.”

This semester, Fensholt decided she couldn’t face a second round. She skipped the three-day lesson on subversion, the cakewalk video, the bell hooks text: “I just didn’t teach it.”

Hannah Natanson is a Washington Post reporter covering national K-12 education.