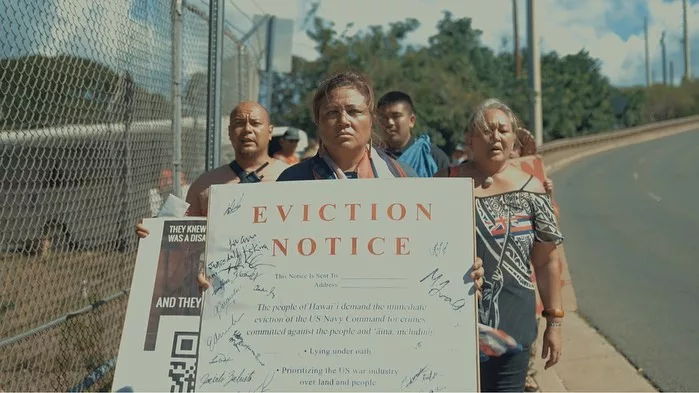

On the 1-year anniversary of the fuel spill, Kānaka Maoli activist and O’ahu Water Protector Healani Sonoda-Pale (center) was among dozens of activists who served members of the Navy Command with an eviction notice.

After a 2021 leak at the U.S. military’s Red Hill fuel storage facility poisoned thousands, activists, Native Hawaiians, and affected military families have become unlikely allies in the fight for accountability.

In late November 2021, in Honolulu, Hawaiʻi, 19,000 gallons of jet fuel leaked from the U.S. Navy’s underground fuel tanks at Red Hill into one of the island’s main drinking water aquifers. It poisoned the water of more than 93,000 people in and around Joint Base Pearl Harbor–Hickam and severely sickened thousands of military families and civilians.

The leak came as no surprise to activists, environmental groups, and government officials who have been fighting against the facility for nearly a decade. Red Hill contains 20 tanks that are each 250 feet tall and can hold a total of 250 million gallons of fuel—and all this has been located just 100 feet above the island’s sole source aquifer.

Built during World War II and classified until the 1990s, the Red Hill facility has since been exposed as a source of multiple leaks since its construction. The November 2021 leak happened weeks after the Hawaiʻi Department of Health fined the Navy for a host of operations and maintenance violations, and a whistleblower reported that Navy officials provided false testimony and withheld information about corrosion at the facility.

In the wake of the 2021 leak, hundreds of water protectors and their alliesdescended onto the state Capitol to demand the immediate shutdown of the facility in Red Hill, a site originally known to Kānaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians) as Kapūkakī. They called out elected officials and the military for putting U.S. imperialism over human lives.

Demonstrators stood in front of a statue of Queen Liliuokalani, the last monarch of Hawaiʻi. She ruled until 1893, when the U.S. Navy aided sugar barons in the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom. The prevailing rallying cry was and has been: “Ola i ka wai” (“water is life”).

“They’ve done so much damage that it will take years, decades to heal from what they’ve done to us,” says Healani Sonoda-Pale, an organizer with the Oʻahu Water Protectors, a coalition working toward environmental justice, sovereignty, decolonization, and demilitarization. “And when I say ‘us,’ I’m talking about the Indigenous peoples of this land who have been under U.S. rule since 1893. As the first peoples of Hawaiʻi, we are the voice of the land, the voice of our water, and our nonhuman relatives. What happens to them happens to us and vice versa.”

Sonoda-Pale’s genealogy on Oʻahu can be traced back hundreds of years. She says she dealt with the trauma of growing up in poverty and watching her family struggle to survive under the grip of U.S. rule. “This gives me the fire and strength to continue on with all of the issues we see in Hawaiʻi,” Sonoda-Pale says. “The fact that my people recovered from the brink of an apocalypse and is still here after 131 years of occupation gives me a lot of hope.”

An Ongoing History of Contamination

This most recent spill was just the Kānaka Maoli’s latest chapter in a century-long fight against the U.S. military and its continued displacement of people and destruction of Native land and natural resources.

“The story of Indigenous people on Oʻahu is a David and Goliath story,” says Sonoda-Pale. “Kānaka Maoli are up against the most powerful military in the world, which also happens to be the biggest polluter in the world. With climate change and global warming looming, our struggle for liberation has become about ensuring a livable future, not just for us but for everyone and all life.”

The U.S. military has come to occupy more than 250,000 acres of land across the island chain, taking up more than 20% of the land on the island of Oʻahu alone. Nearly half of the military’s combined acreage is also on so-called ceded lands, which were annexed illegally without the consent or compensation of Kānaka Maoli or their sovereign government.

The Red Hill fuel facility is just a few miles from Puʻuloa, also called Pearl Harbor. Prior to contact, Puʻuloa was one of the most abundant food sources in the islands, rich with marine resources, and numerous loko iʻa (traditional fishponds) and loʻi kalo (taro patches). It was fed by the water of 12 different watersheds and served as the seat of political power for Hawaiian royalty.

This was destroyed by the dredging of the Pearl Harbor Naval Station in the late 1870s. Today it is one the most contaminated military installations in the nation, with six Superfund sites.

According to a 2007 Congressional Research report, in the waters surrounding Oʻahu, the U.S. military has dumped thousands of bombs, tons of unspecified toxins, hydrogen cyanide, and 4 million gallons of radioactive waste liquid. In 2019, the military was also found to have dumped 500,000 pounds of nitrate compounds—toxic chemicals commonly found in wastewater treatment plants, fertilizers, and explosives.

As recently as January 8, 2024, the Navy released nearly 2 million gallons of partially treated wastewater into Puʻuloa’s waters after heavy rains knocked out a power transformer. This came a year after the Department of Health ordered the Navy to pay $9 million in fines for hundreds of violations of the Clean Water Act at the water treatment plant.

The location of the Pearl Harbor Memorial—the popular tourist destination for the sunken battleship the USS Arizona—is also home to an active oil leak that has been spewing fuel since World War II. Its iridescent toxins float visibly on the water’s surface at all times. Despite having the equipment and knowledge to clean up the spill, the military has chosen not to so as not to disturb the bodies of the 900 service members who lost their lives and remain entombed in the ship. This is a grace the military often hasn’t afforded to the iwi kūpuna(ancestral bones) or sacred sites of Kānaka Maoli.

The Oʻahu Water Protectors have spent the past two years holding the Navy and public officials accountable by creating awareness and helping mobilize thousands of people through social media campaigns, press conferences, protest marches, and calls to action. But these days, for the first time, Kānaka Maoli and their allies are standing together with military families who joined them to demand justice, accountability, clean water, and aid for the military’s affected service people and civilians.

Wayne Tanaka, water protector and director of the Sierra Club, which successfully sued the Department of Health twice over regulations regarding Red Hill, says, “I guess there’s a little bit of irony in [members of the military joining the movement], but also a lot of inspiration. To see people from completely different backgrounds coalescing around the bigger picture—protecting what we need to thrive, what we need to give the best chance to have a bright future for our kids—it’s been so inspiring to witness and gives me hope to come together to tackle some of these existential crises that we’re facing.”

Water Protectors and Military Families Working Together

When families in Kapilina Beach Homes—civilian housing southwest of Joint Base Pearl Harbor–Hickham—began getting ill, they were told by both Kapilina apartment management and the Navy’s emergency operation commander that they weren’t on the Navy water line. After that was proven to be false, those in Kapilina were offered nothing. Active military members, in contrast, were given water and housing in hotels for months.

The Navy continues to insist the water is safe, despite various residents’ reports of sheens on the water, odors, and health problems. Sampling from the EPA determined there are still hydrocarbons in the water and advised the Navy to investigate the root cause and provide water to affected residents.

Kānaka Maoli veteran Aidyn-Rhys King, with his wife, Mandie, and roommate Xavier Bonilla, were among the several affected in Kapilina. They, alongside Oʻahu Water Protector Mikey Inouye, formed Shut Down Red Hill Mutual Aid (SDRHMA) shortly after the leak, which has been providing water to that community every month since.

In addition to clean water, the SDRHMA collective has also been providing the affected community with political education, resources, and tools to organize themselves for justice and accountability. They also hold community picnics to give military families and others affected a safe forum to share concerns. Through this organizing, they have been able to build solidarity between military families and Kānaka Maoli, so the historically opposing groups can communicate together, learn each other’s histories, and figure out how everyone can show up for each other’s struggles.

“It’s a bridge that many of us never thought to be possible within the next 10 years, but is now possible because of this terrible crisis,” says Inouye.

Jamie Blair Williams, who lived at Red Hill Mauka Army housing, eventually became a core member of the group. Williams, whose spouse is in the Coast Guard, was one of at least 1,700 people who got ill and continued to get ill after drinking and bathing in water that the Department of Health reported had petroleum levels 350 times higher than the department considers safe.

Williams also lost her two dogs, her home, and thousands of dollars in personal belongings contaminated by the water. She, alongside thousands of others, are part of various litigations against their housing complexes and the Navy, who denied their health concerns were related to the fuel leak. A mass tort, with more than 1,000 litigants, is set to go to trial in 2024. Another mass tort claim, in which Williams is the lead plaintiff, will go to trial in 2025.

Williams got involved with the water protectors after she, like many, felt that affected residents were being denied salient information. She posted a video from her home’s security camera showing Army officials talking about hazards worse than fuel on her property. She made the video public on social media in hopes that it would force more transparency from the military.

Inouye amplified the video’s reach on the Oʻahu Water Protectors’ social media pages and invited Williams to a sign waving. Already looking for ways to get involved in the activism, but not sure where to begin, Williams accepted and has since participated in panels, protests, and joined the Oʻahu Water Protectors in a demonstration in front of the White House.

Inouye also helped get her and others associated with the military access to Mākua Valley—5,000 acres of land that was seized during World War II for live-fire practice. Back then, Kānaka Maoli were evicted with the promise that their lands would be cleaned up and returned after the war. Nearly 80 years later, that hasn’t happened, and much of the valley’s native forests and cultural sites have since been destroyed by wildfires.

In 1996, the nonprofit Mālama Mākua formed for the preservation, community access, and return of the valley. Due to a court-sanctioned Cultural Access Agreement in 2002, Mālama Mākua is given cultural access to the valley twice a month, which is how Williams was able to see it. And in December 2023, the military decided to finally stop live-fire training there. Many credit the nonprofit for this decision.

Williams says she came to Hawaiʻi with a very surface-level understanding of the contentious relationship between the military and Kānaka Maoli, but after multiple trips to Mākua, now her understanding is deeper in a way that she says feels knitted into the fabric of who she is. Though she also adds, “As someone who is not Indigenous, the true depth of pain that comes with when you are part of a culture that considers wai (water) and ʻāina (land) as a spiritual part of human existence and the kind of violence that the military then unleashes and how that injures you as a human being, as an individual, and as a community, I’ll just never fully be able to understand.”

Collective Successes

Near the one-year anniversary of the 2021 leak at the Red Hill facility, yet another leak occurred: 1,300 gallons of toxic fire-suppression foam leaked from the facility. The foam is a per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance (PFAS)—a “forever chemical” that does not break down naturally.

Twelve days later, thousands of demonstrators, including the Oʻahu Water Protectors and 65 other organizations, coalesced in a “Walk for Wai.” They were led by Ernie Lau, the manager and chief engineer of the Board of Water Supply, as they marched from Keʻehi Lagoon to the Navy Exchange.

Despite having called for the aquifer’s protection for years, this was Lau’s first time joining to publicly support the group’s efforts to pressure the Navy. “It’s time for me to come out of the box and not be a typical government official that stays in his office,” he told Hawaiʻi News Now.

The Board of Water Supply recently filed a claim for $1.2 billion against the Navy to cover the costs of the crisis.

The collective efforts of water protectors and military-affiliated organizers on Oʻahu over the past two years eventually forced the Department of Defense to order the Red Hill facility be shut down and emptied of fuel. This is after the Department initially fought the facility’s closure. In the fall of 2023, more than 104 million gallons of fuel was removed from the Red Hill tanks. Some 64,000 gallons remain, which are set to be removed starting in January 2024, with permanent closure of Red Hill set for January 2027.

Inouye says the reason why the military responded to their public pressure in such a historic way was because they saw that the situation was so bad that it threatened their future presence on the islands. Many of the 65-year land leases that the U.S. military obtained for a mere $1 in the 1960s will expire starting in 2029. If the leases aren’t renewed, the military may be forced to vacate. Activists have already begun organizing against upcoming renewals.

Many water protectors say they are not done organizing around Red Hill until the last drop of fuel is out of the facility, and there is a guarantee of no future use. Still, the movement they have built has been a success in many ways. They have created lasting systemic change through education, mutual understanding, and learning how to show up for one another’s struggles, which Inouye says involves more of a deep organizing approach within communities.

“It happens at a person-to-person level, neighbor to neighbor. While not as flashy as thousands of people at a protest, it’s the type of work required to build towards disruptions that actually create a crisis for decision-makers of powerful institutions,” says Inouye. This way, he added, when it’s time to mobilize for larger issues, it’s not a call to action for strangers, but a call to action to comrades who have organized their own community.

Water protectors, impacted residents, affected members affiliated with the military, and Sierra Club representatives are also now providing oversight in the shutdown and defueling process in a Community Representative Initiative (CRI)as part of a consent decree the Navy signed with the EPA and the state of Hawaiʻi. After a contentious meeting in December 2023, federal officials did not attend the next meeting in January 2024, saying they wanted to reevaluate the structure, operating procedures, and ground rules of the CRI. The Oʻahu Water Protectors contend that the CRI was created as “propaganda to improve [the military’s] battered image.”

“What’s still up in the air is whether this giant bureaucracy will also be able to acknowledge the bigger picture—that it’s not within our national security interests to jeopardize resources we need to survive the climate crisis, especially water,” Tanaka says.

Kalehua Krug is one of the organizers of Kaʻohewai, a coalition of Hawaiian organizations that erected a ceremonial koʻa, or fishing shrine, in front of the U.S. Pacific Fleet command headquarters days after the 2021 leak. It remains there today to create awareness and serve as a place for the Hawaiian community to gather.

“Education is the only proactive way we have to reshape reality,” Krug says.

Krug is the principal of the Ka Waihona o ka Naʻauao Public Charter School, where students are taught through a culturally informed educational model that centers the Indigenous worldview. He teaches them about kinship with nature and the importance of water so they can appreciate, love, and care for it—and then grow up to have more ethical values around how to treat the world.

Whereas mainstream culture’s attachment to the idea of progress is to leave the past behind, Krug says, “It’s the past that informs the future.’’ He points to the fact that before colonization, Native Hawaiians developed ways to live on the islands sustainably for thousands of years in ecological harmony. With that data, he says, “We’ve got enough science to rebuild the world.” And he says an Indigenous worldview, at this point, is a must for everyone on the planet: “We’ve all got to behave different.”

| Libby Leonard is a freelance journalist with work in National Geographic, Guardian, SF Gate, Modern Farmer, Civil Eats, EcoWatch and others.Connect: Twitter |