Amy Klobuchar was exhausted, exhilarated, shaken by a dizzying mindstorm of joy and pain. She’d been in labor for 18 hours, hadn’t slept in two nights, and now she’d given birth to Abigail and life was everything it could ever be. The baby “had all her fingers and toes and seemed quite healthy, except for some mucus in her throat,” Klobuchar recalled.

The new mother called her parents, filled out forms and finally dozed off.

Before long, someone woke her up: “Suddenly the nurse comes in and says ‘She can’t swallow. Everything comes out her nose,’” said Klobuchar, then a 35-year-old lawyer in Minneapolis, now a 59-year-old senator running for president. “And so from that moment on, it was like a disaster.”

The pediatrician on-call had news: “We think she needs emergency surgery.”

In her first day of life, Abigail was rushed into intensive care, subjected to a battery of scans and tests, and put under anesthesia so doctors could peer down her throat.

As that first day ended, though, a nurse plopped Klobuchar into a wheelchair and her husband, John, rolled her out of the building.

“Your time is up,” a nurse told her.

“And I go, ‘What?’” Klobuchar recalled. “And they said, ‘There’s just no way we can waive it.’”

In 1995, many American mothers faced that same arbitrary deadline: Insurance companies and hospitals, eager to trim costs, were sending women home after a maximum 24-hour stay, even when their babies required further treatment. Opponents of the practice called them “drive-through deliveries.”

Twenty-five years later, Klobuchar traces her political awakening to that moment, when the most fundamental fear any parent can face transformed her into a determined activist.

“I was obsessed with it, reading up on it,” she recalled. “I saw it as injustice for moms. I thought if men had babies, this would never happen. It was one of those one-size-fits-all policies that just didn’t allow for any humanity. You’ve been up for 48 hours, you’re a brand-new mom and you have no idea what you’re doing, and they kick you out. You don’t know if your child’s going to live.”

On that first day of Abigail’s life, Klobuchar’s friends and relatives called to find out when they could visit her in the hospital. You can’t, she had to tell them.

Klobuchar, who made her living representing big telecom companies, was told to sign forms saying she and John had watched the required videos on infant care, even though there’d been no time to see them.

“We lied and signed the forms,” Klobuchar said.

She rolled out of the maternity ward still wearing her hospital gown, heading to a $50-a-night hotel, where she would get precious little sleep. The hospital needed her to return every three hours to pump breast milk for struggling Abigail, who was being fed through a tube in her stomach.

Klobuchar stayed in the gown for three days, hurrying back and forth to the hospital all night long. Her baby would stay in the hospital for a week and then face a precarious and scary first year.

“Literally for the first six months, they thought she had cerebral palsy,” Klobuchar said. “They just didn’t know what was wrong. She had a nose tube for the first three months. That’s how we fed her, through a tube.”

‘Stand up and fight’

Five months after the birth of her only child, Klobuchar made the short drive to St. Paul, Minn., to the state capitol, where she made her first appearance before a legislative committee. The case she argued was her own.

Klobuchar urged lawmakers to “pass a law to protect mothers’ and babies’ rights. … What happened to me after I gave birth should never happen to anyone again. It was barbaric.”

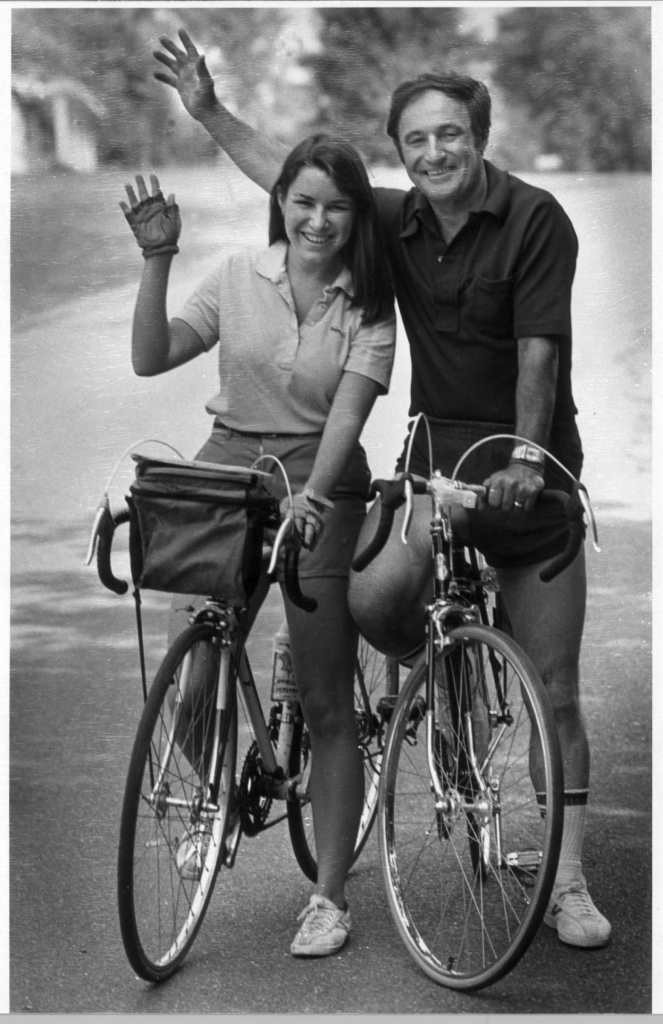

Politics was nothing new to Klobuchar: Her father was a prominent newspaper columnist, she wrote her thesis at Yale on a thorny political issue in Minneapolis, and she’d already been a campaign manager for a county commissioner.

“The incident wasn’t my first rodeo in terms of being interested in politics, but it was in terms of having this gut-wrenching experience and then matching it with action,” she said.

Klobuchar didn’t appear to be a novice at political stagecraft. She brought six visibly pregnant friends to the hearing to be a visual prod for the lawmakers. The idea was to outnumber the insurance companies’ lobbyists.

It worked. It forged a bond with Minnesota voters that has endured to this day — a connection she has thus far struggled to make in Iowa and elsewhere on the presidential campaign trail. And it created an indelible moment that she would use a decade later in a TV ad that some say played a major role in her win in a Senate race.

“She has been smarter at exploiting that story than the reality of how instrumental she was in getting the bill passed,” said Dave Schultz, a political science professor at Hamline University in St. Paul who focuses on Minnesota politics.

But Klobuchar and some of the lawmakers she testified before say her first public venture into the political fray was anything but calculated.

It was a moment when Klobuchar discovered her passion for politics — an early sign she would be a politician who aims, as her campaign slogans have put it, to “get things done.” She would be a practical moderate rather than someone who challenges the system, someone who devotes her energy to pushing for one more day in the hospital, not for a completely new approach to health care.

“It greatly affected how I viewed the world,” Klobuchar said, “because I felt, wow, you know, really bad things can happen to regular people that make no sense at all. And someone’s got to stand up and fight it.”

‘Motherhood and apple pie’

The fight she knew best was the one she’d taken on at home. Her father, Jim, was a household name in Minnesota, a writer at the Minneapolis Star Tribune who chronicled the struggles and triumphs of ordinary people. But as famous as he was, Jim was both a hero and an embarrassment to his daughter.

He was arrested several times for drunken driving; each time, the story appeared in the newspaper where he was a showcased columnist. After one arrest, Amy found the word “drunk” plastered across the front of her school locker.

Amy suffered the stings when her father missed birthdays, vanished on Christmas, went AWOL from her college graduation. She pushed back: She took away her father’s car keys. She did everything she could to impress him, to win back his attention: ran for and won a seat on the student council in high school, became valedictorian.

“I once called the newspaper to try to get their help,” she recalled. “‘Oh, no, it’s fine,’ they said. ‘We just celebrated his sobriety.’ No, it’s not fine.”

In 1993, she staged a full-scale intervention, took her father to an addiction counselor and told Jim she loved him but he had to change.

She was always trying to alter her father’s behavior. “That’s a common trait of a kid of an alcoholic,” she said. “And I always think it’s so interesting: Someday, studies should be done of how many kids of alcoholics or people with drug addictions get involved in politics. You see this wrong and you want to fix it your whole life, and in my case, I was successful, actually.”

Her father stopped drinking, but his daughter kept trying to fix things.

She took an express lane to success: Yale, University of Chicago Law School, a big law firm. Former vice president Walter Mondale became a mentor. And she began climbing the ladder of local politics — party activist, convention delegate, campaign worker.

“It was clear she was going into elective politics,” said Mark Andrew, the former Hennepin County commissioner whose reelection campaign Klobuchar ran in 1990.

Klobuchar devotes the single longest chunk of her presidential campaign stump speech to the tale of her fight against drive-through deliveries. She gets a big laugh from Iowa audiences with a line she first used in her maiden speech before Minnesota legislators a quarter century ago:

“I learned a very valuable lesson. Back then, it was almost all men on the committees, and if you talk about really embarrassing things like episiotomies, they would, like, let you pass the New Deal.”

Audiences adore her story about bringing pregnant friends to pack the hearing room. And they applaud when she takes credit for the win. “So that was how we passed one of the first laws in the country guaranteeing new mothers and their babies a 48-hour hospital stay,” she says.

Victory has a thousand fathers, the old saying goes.

Don Betzold, the state senator who proposed the bill to end the 24-hour limit on mothers’ hospital stays, recalled the effort as the highlight of his career in the legislature. He said he drafted the bill after his wife, Leesa, was required to leave the hospital one day after their son, Ben, was born. Leesa later brought her infant to sit with her in the gallery to watch the debate on her husband’s bill — a move that one legislative leader told her was “unfair.”

Joe Opatz, the sponsor on the House side, also said the drive-through deliveries bill was “the most significant legislation I was involved in.” He too was motivated by personal trauma — the birth of his son and the hospital’s decision to send his wife packing. “We got home and Simon was struggling and we had to take him back to the ER,” Opatz said.

It was Opatz who got the call from Klobuchar, offering herself as a witness.

“Amy packed the conference room with these pregnant women and they made a pretty big impression,” Opatz said. “She’d had a much more traumatic experience with her daughter than I had with our son. The lobbyists for the hospitals and insurance companies tried to delay the bill and kill it, but the public response was amazing.”

Like Opatz, Betzold recalls Klobuchar as “a compelling witness — she was great.”

But by the time the drive-through deliveries issue blossomed in Minnesota, it had swept through much of the nation, and the insurance companies and hospitals fighting to keep the 24-hour limit had taken their defense underground, making their arguments largely behind closed doors for fear of public confrontations with angry mothers and pregnant women.

The insurance industry’s arguments were never going to be popular; an internal memo from the Kaiser Foundation Health Plan defended “the Eight-Hour Discharge” of new mothers by saying it helped mothers because “hospital food is not tasty” and it helped employees because the policy would “reduce our overhead costs.”

Klobuchar talks about Minnesota’s law requiring a minimum 48-hour stay as one of the first, but in 1995, the rebellion against drive-through deliveries “was one of the fastest-moving issues I ever saw,” said Kathryn Moore, who runs state government affairs for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, which argued against the 24-hour limits.

The movement against those quick hospital exits was part of a nationwide backlash against managed care, the then-new system in which health-care companies put even stricter limits on patients’ access to care.

“New Jersey and Maryland were first,” Moore said. “Then it just took off.” Laws requiring a longer minimum stay passed in three states in 1995 and another 25 in 1996. “It was just a groundswell of pregnant women with their babies. We didn’t have to lobby on this — it was organic, spontaneous, the perfect storm. Motherhood and apple pie, David vs. Goliath.”

There was some pushback against change in Minnesota. A House member and family doctor, Richard Mulder, led the charge for keeping the 24-hour limit, saying he had delivered a thousand babies and had only rarely seen anyone who needed to stay more than a day in the hospital.

“I made sure my wife stayed in the hospital five days,” said Mulder, now 81, “but then she told me it was a waste of time and money. And I did some research and found that many mothers couldn’t afford the longer stay and in most cases, it just wasn’t necessary.”

Mulder, a Republican who says his defense of the 24-hour stay got him elected against an incumbent Democrat he portrayed as a big spender, scoffed at the show Klobuchar put on: “Heck, I could get a hundred mothers to come to a hearing to say that, but that’s not science.”

But Mulder was realistic enough to see that Klobuchar’s maneuver would likely succeed: “You always get more votes if you side with the little guy, in this case, the baby. Amy was easy to talk to, and she charmed them, but she didn’t know what she was talking about.”

Mulder’s lobbyist allies shied away from public battle, especially after, as Betzold recalled, an insurance company lobbyist testified that insurers shouldn’t have to pay for women “to take a vacation” after giving birth.

“His remark was not well received,” Betzold said.

“The lobbyists saw the handwriting on the wall,” Opatz said. “All they could do was try to delay implementation of the 48-hour requirement.”

Klobuchar spoke to legislators for 12 minutes. She was passionate, emotional, funny. “You could tell right away she had a knack for it,” Opatz said.

By a vote of 126 to 8, the Minnesota House passed the bill giving mothers and babies an extra day in the hospital.

The episode pushed Klobuchar into a new chapter of her career. As she puts it in her campaign stump speech this year, “the next thing that I did is just kind of start running for office.”

Actually, she had announced the year before Abigail was born that she was running for county attorney, the chief prosecutor position in the area around Minneapolis. But she had withdrawn immediately when the incumbent, an ally of hers, decided to seek another term. Now, she geared up to compete for the job in the 1998 election.

The push for the 48-hour law changed how she presented herself in politics: “Women’s and family issues rose up her list of priorities,” said Andrew, the county commissioner whose campaign she had run. “Before that, she was a do-gooder, very much a good government person, focused on transparency.”

But after the drive-through deliveries debate, Klobuchar’s focus shifted from opening up public records to kitchen table and family issues, especially those of importance to women. For Klobuchar, policy had hit home.

Her mother’s daughter

Klobuchar’s story was set. She won the prosecutor’s job with a get-tough appeal, under the slogan, “Safe Streets. Real Consequences.” But she talked to audiences “all the time about the experience with Abigail,” according to a person who was involved in the early campaigns and spoke on the condition of anonymity to maintain a relationship with Klobuchar. “It was how she humanized herself and demonstrated that she can get things done.”

Eight years later, running for Senate, her campaign ran a TV ad about the drive-through delivery fight. Over melancholic music and a heartbreaking image of newborn Abigail in an incubator, Klobuchar describes how her daughter was “hooked up to machines” while the hospital kicked the new mother out the door. The music swells and Abigail, a decade older, twirls around as she walks between her parents and her mother tells the story.

That joyful spin and Abigail’s double thumbs-up at the end of the ad were “just normal” for her, Klobuchar said. “They didn’t tell her to do that. And then we put that on our Christmas card. It became her signature thing.”

The ad was a hit, “one of the smartest political ads I’d ever seen in Minnesota,” said Schultz, the political scientist. “She was running maybe three points ahead, and she runs that ad and her lead jumps up to 13 or 14 points and she never has to look in the rearview mirror again. She got about 60 percent of the women’s vote. It was pinpoint accurate in hitting suburban women.”

But some Minnesota Republicans say that’s not how it happened, arguing that the election turned instead on the unpopularity of President George W. Bush and the Iraq War. “It’s a nice, after-the-fact narrative,” said a senior adviser to Mark Kennedy, Klobuchar’s opponent in that race, who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

Klobuchar hasn’t faced a serious challenge since that first Senate election. She has made her name in Washington on issues such as toy safety, swimming pool standards, anti-sex trafficking measures and clearing the backlog of rape kits in sexual assault cases — topics that sidestep the usual partisan divisions.

“She’s never really pushed on more controversial issues,” Schultz said.

Klobuchar sees herself as consistently pressing against “entrenched interests. And it started from that moment when I did the maternity bill,” she said. “Yes, it was about women and how women are treated in the health-care system. But I think at its core, it was about injustice.”

After the hospital stay debate, she said, she went from caring mainly about things like “What’s the best policy on recycling?” to “using the limited power that I have as one senator … to take on lead in toys” — issues people face at home every day.

“It’s always been a huge motivation for me when I think people have been basically screwed,” Klobuchar said.

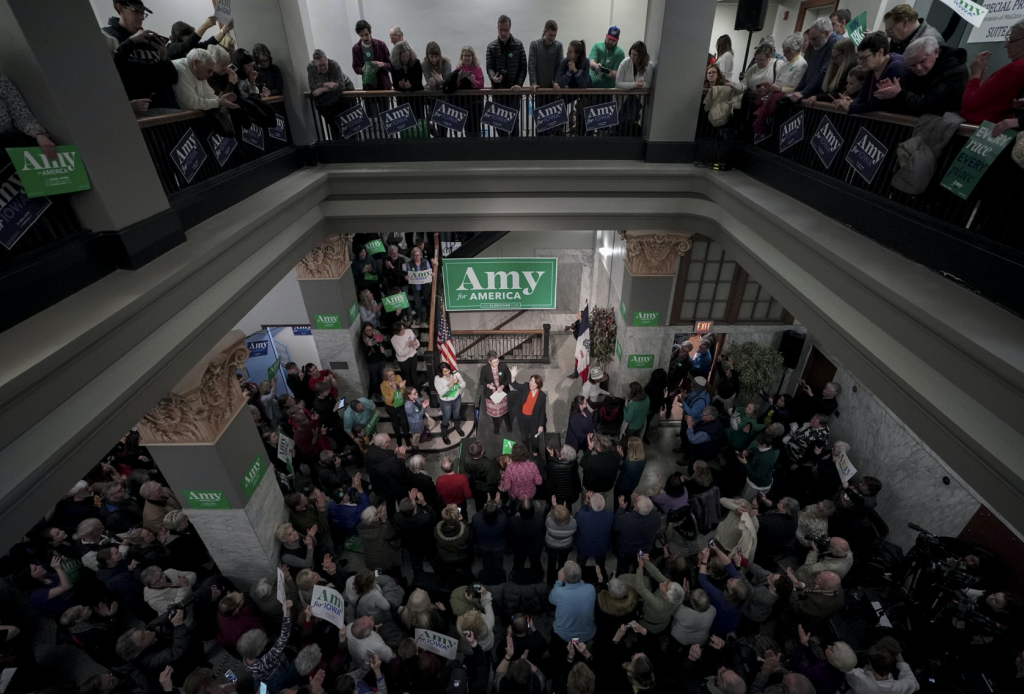

Now, in the final days before the Iowa caucuses that could either propel her into the top rung of candidates or make it tough for her to continue in the race, Klobuchar is stuck in Washington, serving as a juror in President Trump’s impeachment trial.

She’s had to leave much of her campaigning to surrogates, friends and relatives who talk about her tenacity and spell out her ideas. One of those surrogates also reveals Klobuchar’s recipe for hotdish, a Minnesota casserole, her version of which contains ground beef, tater tots, cream of mushroom and cream of chicken soups, and a load of cheese.

The surrogate does not twirl, but nonetheless steals the show. She’s a 24-year-old aide to a New York city council member. Her name is Abigail Klobuchar Bessler.

Marc Fisher, a senior editor, writes about most anything. He has been The Washington Post’s enterprise editor, local columnist and Berlin bureau chief, and he has covered politics, education, pop culture and much else in three decades on the Metro, Style, National and Foreign desks.