When people think about the colonisation of Australia, they might think about it starting in 1788.

That’s the date commonly taught in schools, and is when the First Fleet arrived and established a settlement at Sydney Cove on January 26 — now known as Australia Day.

But it’s what played out 46 years later, when the colonisation of Victoria began in earnest, that’s been in the spotlight as part of the state’s ambitious truth-telling inquiry.

Warning: This story contains details some audience members may find distressing.

Last week, the Yoorrook Justice Commission heard about the unprecedented spread of European settlers throughout the area now known as Victoria in the 1830s.

University of Tasmania history professor Henry Reynolds said it led to so much violence against Aboriginal people, the British government of the day was concerned things had gone “terribly wrong”.

Multiple witnesses told Yoorrook the initial settlement of Victoria was considered illegal by the British government, which had placed limits on the spread of settlement and considered those who went beyond this to be stealing land from the British crown.

These little-known facts about Victoria’s early colonial history were aired as the commission attempts to create an official record of the at-times contested history of the state’s colonisation.

“Victoria, indeed, Australia is having difficulty coming to terms with the truth about the true history and settlement of this country,” Wergaia/Wamba Wamba elder and commission chair Eleanor Bourke said.

Yoorrook is the first Australian truth-telling process of its kind: it has the powers of a royal commission but is led and designed by First Peoples.

Professor Bourke said the effort to document the state’s distressing past through truth-telling was essential.

“It is about creating a shared history, shaping a better future and a new relationship between First Peoples and all Victorians,” she said.

“It should also form part of the education curriculum and training of professionals within this state.”

Last week, Yoorrook heard from two panels of historians, elders and the descendent of a coloniser.

Here’s what they told the commission.Victoria’s violent colonial past has been laid bare in the state’s Yoorrook Justice Commission hearings. WARNING: Some viewers may find this report distressing. It contains descriptions of historical violence.

The colonisation of Victoria began 46 years after the arrival of the First Fleet

After the First Fleet arrived at Sydney Cove in 1788, Europeans established settlements in Tasmania from 1803 and Western Australia’s Swan River colony in 1829.

Following a brief failed settlement at Sorrento in the early 1800s, it wasn’t until 1834 that colonisation in Victoria began, when the Henty brothers established a permanent European settlement at Portland, on Gunditjmara country in the south-west.

That was 190 years ago.

By way of comparison, Yoorrook commissioners recently visited the ancient aquaculture eel traps at Budj Bim, not far from Portland — which are understood to have been created at least 6,600 years ago.

Gunditjmara elder Jim Berg told Yoorrook the period of colonisation being considered by the truth-telling inquiry was a tiny fraction of the country’s Aboriginal history.

The 86-year-old has been alive for nearly half the time that Europeans have remained in Victoria, since the settlement of Portland.

“The story of the most resilient culture in this country, should be and will be told,” Mr Berg said.

The early settlements of Victoria were considered illegal by the British at the time

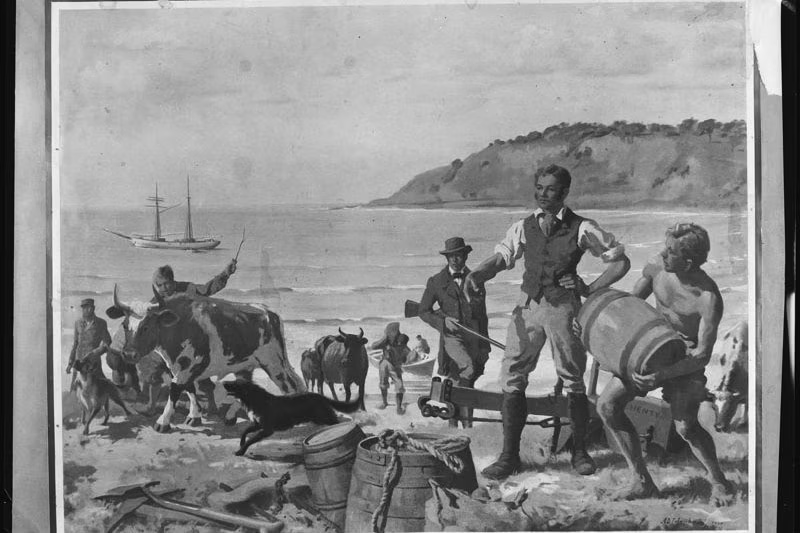

What the Hentys did when they arrived at Portland in 1834 is celebrated in historical monuments around the area and in some history books.

Others, like Kerrupmara/Gunditjmara man and Yoorrook Justice commissioner Travis Lovett, describe what they did as a crime.

“They illegally took our land, our homes and our lives,” he said during a special hearing held at Tae Rak (Lake Condah) on Gunditjmara country.Travis Lovett sits as a commissioner of the Yoorrook Justice Commission.(AAP Image: James Ross)normal

Yoorrook heard the settlement of Portland was illegal in the eyes of the British, too.

La Trobe University historian and professor Richard Broome described the Henty brothers as “middle-ranking” English farmers, who spent time in colonies in WA and in Tasmania before sailing to what is now known as Portland, driven by “land hunger”.

“It was illegal to do so … because the government in New South Wales [which at the time controlled the area now known as Victoria] had tried to limit settlement and there were boundaries beyond which you could not go,” Professor Broome said.

The subsequent spread of settlers throughout Victoria against the wishes of the colonial government spiralled into what Professor Henry Reynolds labelled “a disaster they couldn’t control”.A map of land holdings during the rapid settlement of Victoria.(Supplied: Yoorrook Justice Commission)normal

Professor Reynolds said the boundary of settlement was an area about 300 kilometres from Sydney and those who travelled beyond it had “no legal justification for doing so”.

A sixth-generation descendant of the Henty family, Suzannah Henty, told the Yoorrook Justice Commission her family’s establishment of a settlement was an “invasion” and “the war that ensued was a crime that continues to inflict harm”.

“The family illegally squatted on the Gunditjmara homelands, where they stole and damaged tens of thousands of acres of land and waterways,” she said.

Ms Henty told Yoorrook of the recorded killings of five Aboriginal people in three separate incidents on the family’s sheep run Merino Downs.

Based on the research of Federation University historian Professor Ian D Clark, she also referenced a November 1840 massacre, where an “overseer for the Henty brothers” killed a number of Aboriginal people.Suzannah Henty is a sixth-generation descendant of the Henty brothers who established a European settlement in Victoria in 1834. (Yoorrook Justice Commission: David Callow)normal

“For both the British and First Nations peoples, this settlement was a crime,” Ms Henty said.

Colonial authorities of the 1830s were concerned about violence against Aboriginal people

Professor Reynolds said inside the colonial corridors of power, private correspondence revealed significant concerns about the deadly violence being carried out across Victoria during the squatting rush.

“They were saying this was terrible, and it is likely that the Aboriginals will become exterminated,” Professor Reynolds told Yoorrook.There were 49 known massacres in Victoria where more than 1,000 Aboriginal people were killed. (Public Records Office)normal

In his evidence to Yoorrook, Professor Reynolds read a note written on a letter from Australia in April 1838 by a man named James Stephen, who worked in the British colonial office.

“The causes and consequences of the state of things are clear and irremediable … nor do I suppose it is possible to discover any method by which the impending catastrophe, namely the extermination of the black race can be averted.”

In 1837, a British government committee report on Aboriginal people expressed serious concern about the suffering of Indigenous people in Australia.

“These people, unoffending as they were towards us have as might have been expected, suffered in an aggravated degree from the planting amongst them of our penal settlements,” the report stated.

“In the formation of these settlements it does not appear that the territorial rights of the natives were considered.

“Very little care has since been taken to protect them from the violence or contamination of the dregs of our country men … the effects have consequently been dreadful beyond example, both in the diminution of their numbers and in their demoralisation.”

The spread of squatters throughout Victoria was unprecedented, quick and violent

Not long after the Henty brothers began to settle in Portland, from about 1835, following the voided treaty of John Batman, squatters started rapidly arriving into the area now known as Victoria.

Squatters travelled from Tasmania and from the north over the Murray, against the wishes of the colonial government.

Professor Reynolds told Yoorrook the “squatting rush” in Victoria was an “extraordinary development” unlike anything else in the “history of European colonisation”.A drawing by Edward William Jeffreys of the view from Pentland Hills looking towards Melbourne from 1850. (State Library Victoria)normal

Professor Broome told the commission it was likely the “swiftest expansion within the British empire of any occupation of land”, in part due to the desirable sheep country that was created by “firestick farming”.

Unable to stop the spread of the squatters — who by the 1840s had established 700 stations and brought millions of sheep into the area now known as Victoria — the colonial government introduced a license, and later a lease system, Professor Reynolds said.

It also marked the acceleration of the end of traditional society for Victoria’s Aboriginal nations, despite their continued resistance.

“This was one of the most tragic periods for First Nations people … both because of the speed of the occupation and undoubtedly the amount of violence and the killing that took place in this period,” Professor Reynolds said.

More than 1,000 Aboriginal people were killed in Victorian massacres

Yoorrook also heard from University of Newcastle researcher Bill Pascoe, who is involved with a project mapping colonial massacres.

There were 49 known massacres in Victoria (a massacre is defined as the killing of six people or more), in which 1,045 Aboriginal people were killed.

Dr Pascoe said that figure excluded some massacres that happened near the Murray, and killings of smaller numbers of people.

“Some of the things I’ve encountered in this research are the worst things I’ve ever heard of anyone ever doing to anyone in human history,” he told the commission.

There was one recorded massacre of colonists in Victoria in which eight people were killed.The University of Newcastle’s map shows a large number of massacres during colonisation occurred in Victoria’s south-west. A blue marker shows an attack which killed eight colonisers in the state’s north-east.(Supplied: University of Newcastle)normal

His data also showed across Australia and in Victoria, the most violence took place in the 1840s and that 16 per cent of the recorded massacres in Victoria involved “agents of the state” like native police or government officials.

This proportion was significantly lower than around the country. Nationally, 51 per cent of massacres involved “agents of the state”.

Professor Reynolds said that was because in Victoria, the killings became “privatised” because of the way the area was settled.

“Because anyone, if you set up 700 pastoral stations, they can all if they want to, send out punitive expeditions … this is so pertinent to Victoria,” he said.

The University of Melbourne’s foundation chair of Indigenous Studies, Marcia Langton, told Yoorrook it was important to recognise those numbers didn’t represent all of the violence that took place during this time.

“These records are the tip of the iceberg … it is unlikely most of the killings were recorded,” Professor Langton said.

Aboriginal population likely crashed by tens of thousands within decades

Drawing on the work of a researcher called Neil Butlin, Yoorrook heard estimates that, based on measures like the availability of traditional foods, 60,000 people may have lived in Victoria pre-European contact.

The population was understood to have been decimated by diseases like smallpox, even before the Europeans had arrived in Victoria.

It may have been transmitted by whalers, or contact with other First Nations groups closer to the settlement in New South Wales.

Professor Broome told Yoorrook by the late 1830s the British were estimating the population at about 10,000.

He said by the early 1850s, when more exact counting had begun, it was less than 2,000.

Yoorrook Justice commissioner Travis Lovett said the telling of this state’s early history was an important step towards justice for First Peoples.

“We invite all Victorians to walk with us. To listen, to learn and share our history,” he said.

The Yoorrook Justice Commission will hold more hearings across Victoria as part of its current inquiry on land injustice in April, before turning its attention to housing and health later this year. Its final report is due in June 2025.

For Gunditjamara elder Jim Berg, who founded the state’s Koorie Heritage Trust, there can be no healing without it.

“Without the truth being told of what happened in this place called Victoria, there can be no reconciliation only a divided state as it is today,” he said.

“Tell the truth.”