As the House impeaches President Trump for a second time, outgoing Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has said the earliest his chamber would start a trial is after Trump has already left office. Whether an official can be impeached after leaving office has not been settled by the courts, and constitutional scholars do not agree on the matter.

There is some historical precedent: The impeachments of Sen. William Blount in 1797 and Secretary of War William Belknap in 1876 both occurred after the men were no longer in office.

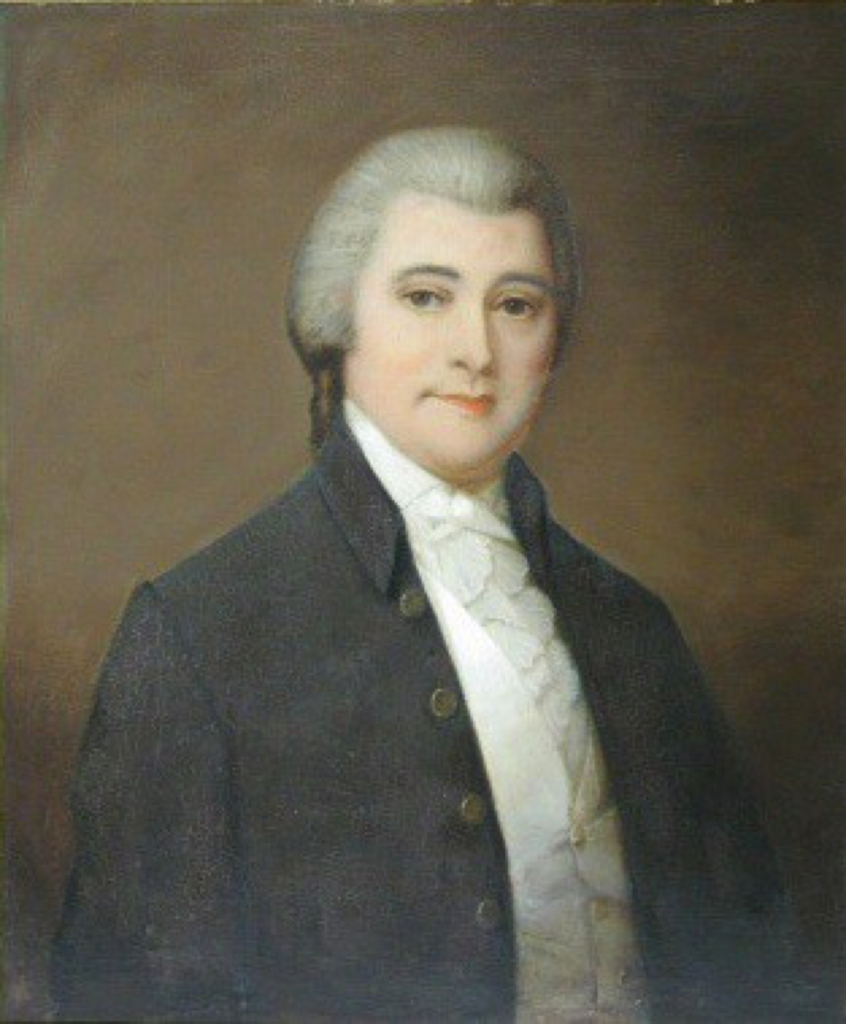

Blount is one of the lesser-known Founding Fathers now, but for much of his life he was as esteemed as the ones we all remember. He fought in the Revolutionary War, was a North Carolina delegate at the Constitutional Convention and signed the Constitution. He then moved to what is now Tennessee and became governor of its territory. When Tennessee became a state, he became one of its first U.S. senators.

Blount was also a land speculator and borrowed money to purchase huge swaths of land in Tennessee and the surrounding areas. After a land-market crash left him in dire straits, he developed a plan to save himself: He conspired with Britain to help it gain control of Spanish Florida and Louisiana, which would make his land purchases valuable again. In 1797, a letter he wrote detailing parts of the plot made its way to President John Adams, who had it read on the Senate floor. The other conspirators soon confessed.

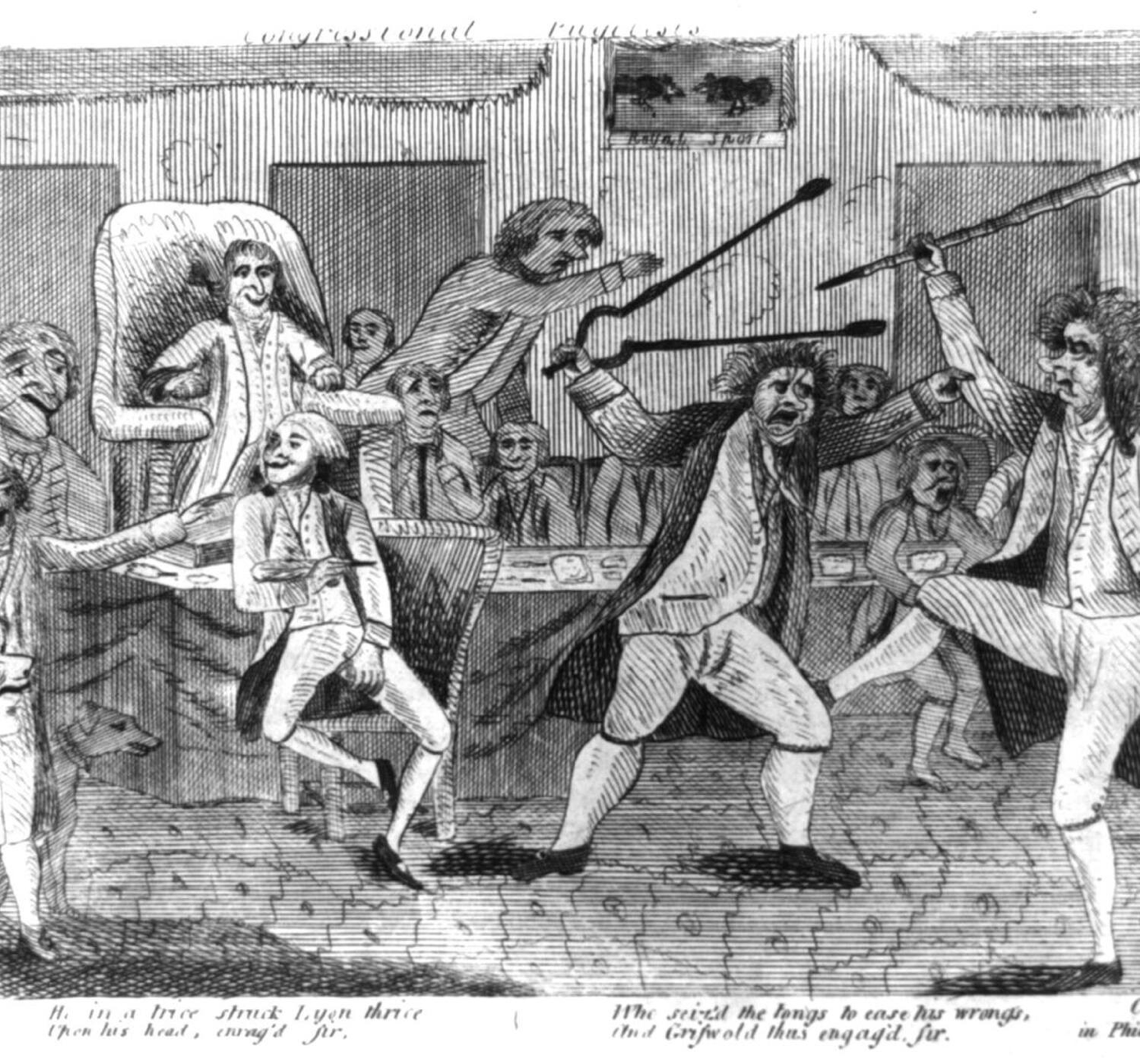

The House and Senate investigated and debated whether the new Constitution allowed senators to be impeached, or only expelled. They did both — Blount became the first senator to be expelled, and the House voted to impeach him. As the Senate prepared for a trial, Blount fled back to Tennessee.

Debate among Federalists and Democratic Republicans swirled around whether they had the right to (a) impeach a senator and (b) impeach an official who had already been expelled. In the end, they voted to stop an impeachment trial without deciding the question. Blount remained popular in Tennessee and held state offices until his death. He was the only U.S. senator to be expelled until the Civil War.

The most popular and interesting stories of the day to keep you in the know. In your inbox, every day.

In 1846, Adams’s son John Quincy Adams, who was president from 1825 to 1829 before becoming a congressman, made his position clear, saying on the House floor, “I hold myself, so long as I have the breath of life in my body, amenable to impeachment by this House for everything I did during the time I held any public office.”

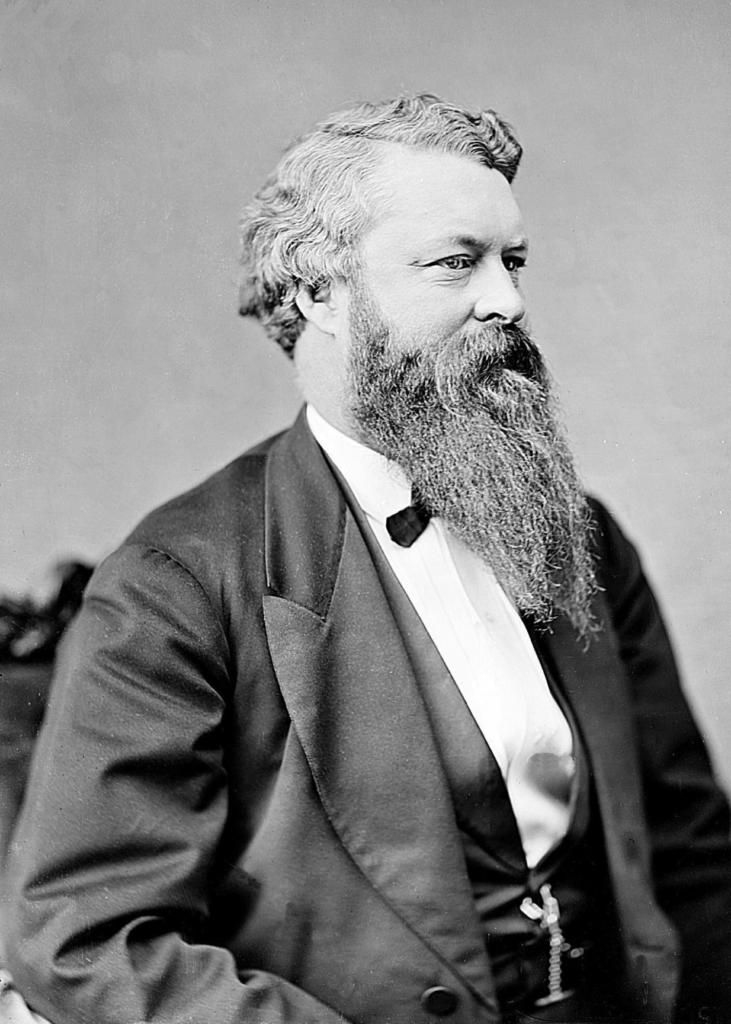

Decades later, the question came up again in the case of Belknap, President Ulysses S. Grant’s longtime secretary of war. Belknap had a reputation for hosting lavish parties, and both his first and second wives went about Washington extravagantly attired.

“Many questioned how he managed such a grand lifestyle on his $8,000 government salary,” according to the Senate Historical Office.

A House committee then solved the mystery: Belknap had been accepting bribes in exchange for profitable contracts, going back to 1870. As the House voted on whether to impeach him, Belknap raced to the White House and resigned, believing this would save him, then “burst into tears.”

The House voted unanimously to impeach him anyway on five counts, including “basely prostituting his high office to his lust for private gain.”

The Senate decided it did have the authority to try former officials and conducted a trial in April and May of 1876. A majority of the Senate voted to convict but failed to meet the two-thirds majority required. He was acquitted and faced no further legal action for his crimes.