More than $1.5 billion has been spent to settle claims of police misconduct involving thousands of officers repeatedly accused of wrongdoing. Taxpayers are often in the dark.

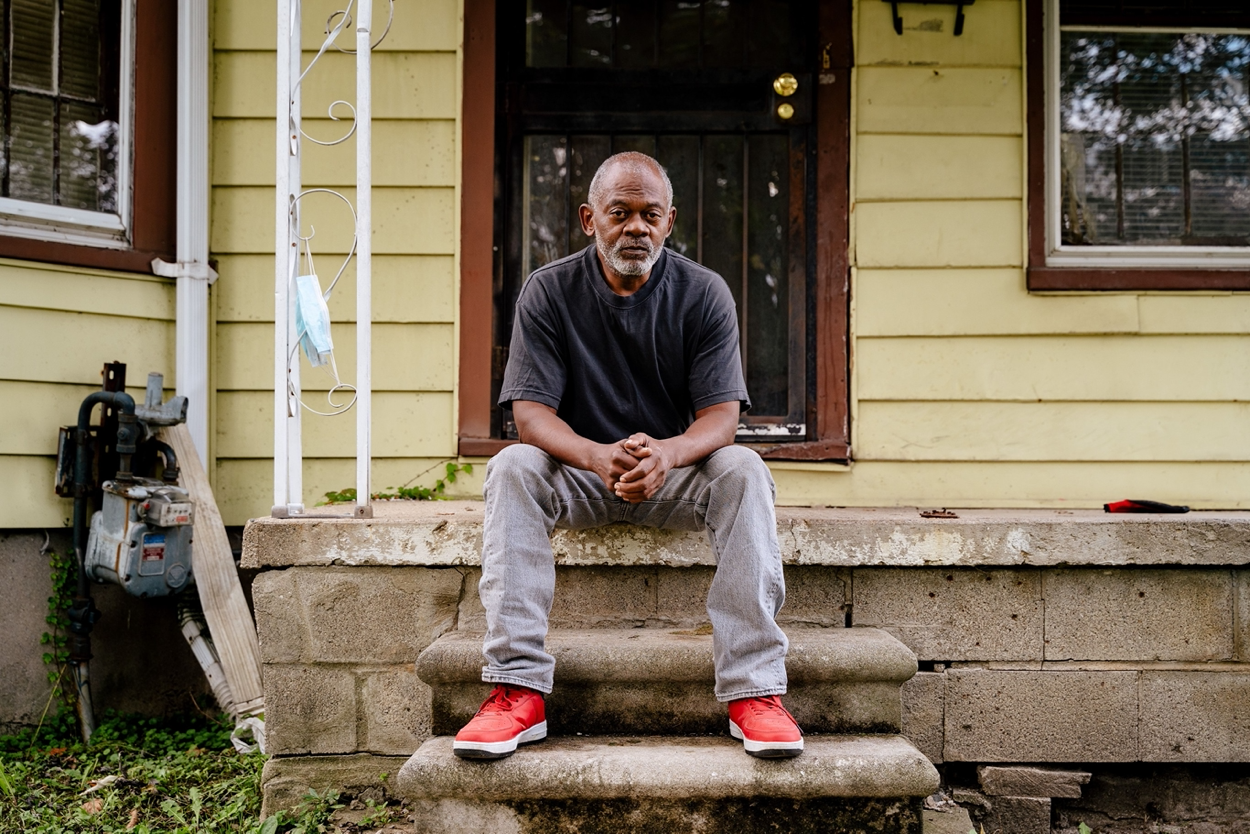

About 8:30 one Thursday evening in Detroit, Tony Murray was getting ready for bed ahead of his 6 a.m. shift at a potato chip factory. As he turned off the final light in the living room, he glanced out of his window and saw a half-dozen uniformed police officers with guns drawn approach his home.

As the officers banged on the door, Murray ordered Keno, his black Labrador retriever, to the basement. As Murray let the officers in, one quickly pushed him to the floor and at least two others ran to the cellar, he said. “Don’t kill my dog. He won’t bite you,” Murray pleaded. The sound of gunshots filled the house. Keno’s barking, the 56-year-old recalled, morphed into the sound of “a girl screaming.”

Officers searched Murray’s home for nearly an hour, flipping his sofa and emptying drawers. Outside, Murray approached the officers standing by their vehicles. One handed him a copy of the search warrant, which stated they were looking for illegal drugs. Murray noticed something else: The address listed wasn’t his. It was his neighbor’s.

Months after the 2014 raid, Murray, who was not charged with any crimes, sued Detroit police for gross negligence and civil rights violations, naming Officer Lynn Christopher Moore, who filled out the search warrant, and the other five officers who raided his home. The city eventually paid Murray $87,500 to settle his claim, but admitted no error by police.

That settlement was not the first or last time that Detroit would resolve allegations against Moore with a check: Between 2010 and 2020, the city settled 10 claims involving Moore’s police work, paying more than $665,000 to individuals who alleged the officer used excessive force, made an illegal arrest or wrongfully searched a home.

Moore is among the more than 7,600 officers — from Portland, Ore., to Milwaukee to Baltimore — whose alleged misconduct has more than once led to payouts to resolve lawsuits and claims of wrongdoing, according to a Washington Post investigation. The Post collected data on nearly 40,000 payments at 25 of the nation’s largest police and sheriff’s departments within the past decade, documenting more than $3.2 billion spent to settle claims.

The investigation for the first time identifies the officers behind the payments. Data were assembled from public records filed with the financial and police departments in each city or county and excluded payments less than $1,000. Court records were gathered for the claims that led to federal or local lawsuits. The total amounts further confirm the broad costs associated with police misconduct, as reported last year by FiveThirtyEight and the Marshall Project.

The Post found that more than 1,200 officers in the departments surveyed had been the subject of at least five payments. More than 200 had 10 or more.

UNACCOUNTABLE: Read more from this investigation

An examination of policing in America amid the push for reform.

The repetition is the hidden cost of alleged misconduct: Officers whose conduct was at issue in more than one payment accounted for more than $1.5 billion, or nearly half of the money spent by the departments to resolve allegations, The Post found. In some cities, officers repeatedly named in misconduct claims accounted for an even larger share. For example, in Chicago, officers who were subject to more than one paid claim accounted for more than $380 million of the nearly $528 million in payments.

The Post analysis found that the typical payout for cases involving officers with multiple claims — ranging from illegal search and seizure to use of excessive force — was $10,000 higher than those involving other officers.

Despite the repetition and cost, few cities or counties track claims by the names of the officers involved — meaning that officials may be unaware of officers whose alleged misconduct is repeatedly costing taxpayers. In 2020, the 25 departments employed 103,000 officers combined, records show.

“Transparency is what needs to be in place,” said Frank Straub, director of the National Police Foundation’s Center for Mass Violence Response Studies, adding that his organization has called for departments nationwide to publicize cases with settlements. “When you have officers who have repeated allegations … it calls for extremely close examination of both the individual cases and the totality of the cases to figure out what’s driving this behavior and these reactions and to see if there is a pattern in an officer’s behavior that triggers these cases.”

Defenders of police have a different view.

City officials and attorneys representing the police departments said settling claims is often more cost-efficient than fighting them in court. And settlements rarely involve an admission or finding of wrongdoing. Because of this there is no reason to hold officers accountable for them, said Jim Pasco, executive director of the National Fraternal Order of Police, the nation’s largest police labor union with more than 364,000 members.

“If there’s never been a finding of guilt or anyone’s fault, why put that in an officer’s record?” Pasco said. “That would be such a glaring omission of due process where in the legal system in the United States, a person is innocent until proven guilty.”

The Post reached out to scores of officers named in claims that led to payments. Some were no longer working for the departments. Most had no comment or, like Moore, did not return phone calls.

Two officers in Boston who had the highest number of claims settled have since retired. But both said the allegations — ranging from excessive force to wrongful arrest — did not accurately portray their work while on the force.

Paul Murphy, who was named in four lawsuits totaling about $5.2 million in payments, said he “tried to do the best he could” as an officer. But he added, “sometimes things happened.” He declined to elaborate.

Gerald Cofield was named in three lawsuits that totaled about $306,000 in payments. Cofield said he wished the city had fought the claims instead of settling because he believed city attorneys would have won, and his name and reputation would have been cleared. “We are not the bad guys these lawsuits paint us to be,” he said.

One Detroit officer said he wished the city had fought the lawsuits because he believed the cases had no credibility and those making the allegations had been armed or resisting arrest. “It’s called the Detroit lottery,” said the officer, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he had not received permission to speak publicly. “People have been convicted and are in prison filing lawsuits knowing they can get paid.”

Multimillion-dollar settlements regarding allegations of police misconduct often generate headlines. Minneapolis paid $27 million to the family of George Floyd, and Louisville paid $12 million to Breonna Taylor’s family.

Those cases are the exception: The median amount of the payments tracked by The Post was $17,500, and most cases were resolved with little or no publicity.

Many of the officers who had the highest number of claims against them were participating in task forces targeting gangs, drugs or guns, records show.

Pasco said he is not surprised that these officers would be the subject of multiple lawsuits, given the assignments. And given, he said, that the nation has become a “litigious society.”

“It’s the cost of policing,” he said. “That’s the reason crime, until recently, has declined.”

New York, Chicago and Los Angeles alone accounted for the bulk of the overall payments documented by The Post — more than $2.5 billion. In New York, more than 5,000 officers were named in two or more claims, accounting for 45 percent of the money the city spent on misconduct cases. In New York, four attorneys who have secured the highest number of payments for clients separately said the high rate of claims is because of poor training, questionable arrests and a legal department overwhelmed by lawsuits.

In Philadelphia, six officers in a narcotics unit generated 173 lawsuits, costing a total of $6.5 million. In 2014, those officers were federally charged with theft, wrongful arrest and other crimes but eventually acquitted at trial. Some 50 additional lawsuits are pending, many alleging misconduct dating back more than a decade, said Andrew Richman, a spokesman for the city’s legal department.

In Palm Beach County, Fla., officials paid out $25.6 million in the past decade: One-third of that was generated by 54 deputies who were the subject of repeated claims.

The data provided by cities included no demographic information about the people who filed the claims. But Chicago attorney Mark Parts, who has handled scores of lawsuits against police, said most of his clients have been Black or Hispanic.

“The folks who are aggressively policed and confronted by officers in the course of their daily lives are people of color,” Parts said. “I have found the majority of those whose rights are repeatedly violated are African Americans and Hispanics.”

In the D.C. region, more than 100 officers have been named in multiple claims that led to payments.

In Prince George’s County, Md., 47 officers had their conduct challenged more than once, resulting in at least two payments each accounting for $7.1 million out of $54 million paid within the decade. Two in five payments involved an officer named in more than one claim. The totals are skewed by a $20 million payment to the family of 43-year-old William Green, who was fatally shot while his hands were cuffed behind his back in the front seat of a police cruiser.

Cpl. Clarence Black was the subject of four settled cases, the most in the department. In 2010, the county paid $125,000 to a husband and wife who alleged Black assaulted them. In 2013, a Temple Hills family received $60,000 after alleging Black and four other officers illegally entered their home. In 2014, a woman got $10,000 after alleging Black punched her shoulder. And in 2019, a man collected $190,000 after alleging that Black illegally handcuffed him as he retrieved a bottle of water.

Black, a former officer of the year who joined the force in 2002, was indicted in August on two counts of second-degree assault and two counts of misconduct in office after being accused of assaulting a driver during a traffic stop in Temple Hills. Black’s attorney did not return calls requesting comment. He has pleaded not guilty and is scheduled to go to trial in July.

In the District, 65 officers have been named in repeated claims, accounting for $7.6 million of the more than $90 million in claims paid — the fifth-highest overall of the 25 cities surveyed. That total includes $54 million paid on four claims involving officers who were named in no other cases.

Officer Fredrick Onoja was the subject of five cases that led to payments from 2014 to 2019 totaling $116,000, the most of any officer on the force. Five Black men separately sued Onoja accusing him of wrongful arrests and harassment. They alleged that the 44-year-old Onoja — who has been on the force since 2011 — fabricated evidence against them in the 5th District neighborhood he patrolled.

Dustin Sternbeck, a D.C. police spokesperson, said Onoja had been “disciplined” for his actions, but declined to elaborate. Onoja, through the department, declined to comment. In a statement, Sternbeck said the department investigates allegations against officers made in lawsuits. “If the investigation sustains misconduct, the department takes appropriate action, ranging from retraining to termination, depending on the nature of the misconduct sustained,” he wrote.

In Fairfax, the county settled seven cases, totaling $6.1 million. Two of the cases involved five officers and led to $5 million in payments. Only one officer was named in more than one claim.

Officer Hyun Chang, who has been with the department since 2010, was the subject of a claim that resulted in a $750,000 settlement in 2018 with the family of a 45-year-old autistic man who died in 2016 as he was subdued by Chang and another officer. According to police, the victim, Paul A. Gianelos, of Annandale, Va., became combative as the officers tried to return Gianelos to his caretakers. A Virginia medical examiner determined Gianelos died as a result of a heart attack related to the restraint.

In 2014, Chang was one of a dozen officers named in a $190,000 settlement after a Hispanic woman charged the officers with excessive force, false arrest, unreasonable search of her home and racial profiling. He did not return requests for comment through a Fairfax police spokesperson.

In general, the government officials in many of the cities who were interviewed said the decisions to settle claims are made on a case-by-case basis.

In Chicago, officials “evaluate cases for potential risk and liability, and to take appropriate steps to minimize financial exposure to the city,” said Kristen Cabanban, spokesperson for the city’s Law Department.

It is often cheaper to settle a case than pay attorneys’ fees “that in many cases dwarf the actual damages award,” said Casper Hill, a spokesman for the city of Minneapolis.

Even when payments are covered by insurance claims, taxpayers ultimately still pay as those claims drive up the cost of the insurance.

The Post found that few cities publicize their payments or make it easy for the public to identify the officers involved. Of the 25 cities surveyed, four reported tracking payment information. The others declined to answer or said they were unaware of any city department that did such tracking.

Minneapolis, Palm Beach County, Fairfax County and Detroit were among the few places that recorded payments by officers’ names in the records provided to The Post. Portland organized cases by the officers’ badge numbers.

Most cities reported payments by the name of the person who filed the claim or, if the case led to a lawsuit, the number assigned in court. The Post identified the officers involved in tens of thousands of cases by reviewing individual claim summaries and court records.

There are disincentives to such tracking, legal and policing experts said.

“If an officer has multiple lawsuits, then the city is in jeopardy of negligent retention,” says Stephen Downing, a retired deputy chief with the Los Angeles Police Department and current adviser with the Law Enforcement Action Partnership, a criminal justice reform group. “Few cities want to risk retaining that information to avoid being part of an even more costly lawsuit.”

Policing experts also noted that prosecutors rely on officers to testify in criminal cases; settlement tracking could be used by defense attorneys to challenge an officer’s credibility.

The $10,000 air freshener

In Portland, Officer Charles B. Asheim, 40, was the subject of three payments costing the city $40,001. The city spent more than $90,000 in legal fees fighting those three claims and $250,000 defending three other claims involving Asheim that resulted in no payments, according to Heather Hafer, a spokeswoman with the city’s Office of Management and Finance.

In 2014, Marqueeta Clark and her then-boyfriend, Jahmarciay Barr, were leaving Barr’s aunt’s house on their way to the movies in Barr’s blue 1991 Chevrolet Caprice. At the time, Clark was a 19-year-old early-childhood education major at Western Oregon University, and Barr was a 20-year-old community college student and UPS employee.

As the couple drove along the highway, they saw a police cruiser heading in the opposite direction.

Seconds later, Clark said, they noticed the cruiser make a U-turn and begin to follow them. Barr stopped at a traffic light with the cruiser behind them. When the light turned green, as they pulled away, the cruiser’s lights came on and police pulled them over.

Asheim, an officer with the gang unit, told the couple they were stopped because Barr had changed lanes without using his turn signal, Clark said. She said she disputed the claim, telling police she could hear the blinker’s ticking.

Then Asheim, she said, one of three officers at the scene, told the couple that police had pulled over the car because there was a green, pine-tree air freshener dangling from the car’s rearview mirror. The air freshener, Asheim told them, obstructed the driver’s line of sight and created a driving hazard, she said.

Barr, still seated in the car, grew angry and refused to cooperate with Asheim when the officer asked for his driver’s license and registration, she said.

Sitting in the passenger seat, Clark said she begged the officers to allow her to reach into the glove compartment to pull out Barr’s documents. But Asheim refused and continued to argue with her boyfriend, she said. “In my head, I was thinking these gang task forces are going to treat us as gang members. … I was terrified,” she said.

Asheim then pulled Barr through the driver’s side window and placed him in handcuffs, she said.

In his official report, Asheim gave a different account: He wrote that he and his colleagues unhooked the driver’s seat belt, opened the door and forced Barr to stand up outside the vehicle. Asheim added that Barr accused police of stopping him because “he was Black.” The officers, according to Asheim’s report, “calmly and simply” explained the reason for the stop, but the boyfriend “continued screaming.”

Asheim also noted that Barr was becoming more “threatening and unpredictable,” and that he threatened to “kick our f—ing ass.”

Clark denied that Barr threatened the officers. “I remember watching Asheim laughing at us. It was really humiliating, embarrassing and frustrating.”

The officers searched the car and found nothing illegal, according to the police report.

Police arrested the couple. Clark was charged with interfering with a police officer and disorderly conduct. Barr, who could not be reached for comment, was charged with failure to carry and present his license, disobeying an officer and disorderly conduct. He pleaded guilty to failure to carry and present a license and was ordered to pay $250 in fines. Prosecutors dismissed the other charges against him.

Clark chose to fight her charges. Eventually, the judge dismissed the case.

Still, Clark remained furious. She and Barr sued the city, alleging that the stop by Asheim — who is White — and his two colleagues was part of a pattern of racially discriminatory police tactics. “I really wanted people to know how the majority of the Black community was being treated by police,” she said. “It was never about the money for me.”

Growing up in Portland, Clark said being stopped by police and having guns drawn was “the norm for us.” She said that she and her boyfriend were stopped by police about a half-dozen times in a four-year period.

In 2017, the city agreed to settle their claims, eventually paying Clark and Barr $5,000 each. Officials did not apologize or admit wrongdoing.

They were among the city’s 89 payments for alleged police misconduct during the past decade. Of the more than $7.5 million spent, nearly half of it has involved officers named in more than one claim.

“What Asheim did, stopping people for having an air freshener hanging from the rearview mirror, was the practice of the gang enforcement team,” said Gregory Kafoury, Clark’s attorney. “These officers were driving around and obviously looking for Black faces.”

Kafoury said he has represented dozens of people in lawsuits against Portland officers, the majority of his clients people of color.

“Historically, officers who are sued are never penalized, even when the city has to pay large settlements or verdicts for their misconduct,” Kafoury said. “The officers who are the most brutal and the most dishonest tend to move up in the ranks because they are seen as trustworthy and they are admired for their physicality. And that culture gets strengthened as these types of bullies move up and control the culture of the police department.”

Sgt. Kevin Allen, a Portland police spokesman, denied Kafoury’s assertions. “Our promotions process is extremely competitive and thorough and includes a 360-review in most ranks, taking in the candidate’s discipline record, commendations, community engagement and more,” Allen said.

Asheim has been with the force for 13 years and is a detective, Allen confirmed. He declined to answer questions about Asheim or the cases that led to settlements. Allen said he forwarded The Post’s request for comment to Asheim, who has not responded.

‘I’ll never forget him’

Early one evening in March 2014, Gregory Williams, 34, was walking to buy cigarettes at a gas station on the west side of Chicago. A man rushed up behind him, hit him on the head with a gun and pushed him against a fence, Williams said. He thought he was being robbed.

The man, however, was a Chicago police officer in plain clothes.

An unmarked police car pulled up. Inside was Officer Armando Ugarte — who from 2010 through 2020 would be a subject of 16 payments totaling more than $5 million for claims that included excessive force and wrongful arrests.

That night, Ugarte and two other officers told Williams, a father of two and student at Strayer University, that they were arresting him for distributing a controlled substance: heroin. They drove Williams to a precinct called Homan Square, a former Sears and Roebuck warehouse that police used as an interrogation site.

While he was handcuffed, Williams said, Ugarte and the other officers pressed him to identify heroin dealers. When he said he could not, he alleges that they grabbed him by his neck, put him in a chokehold, threw him to the floor and punched and kicked him.

“I’ll never forget him,” Williams said about Ugarte.

In the arrest report, Ugarte wrote he had purchased drugs from Williams as part of a “controlled buy” that night while working undercover. Williams was charged with two counts of felony manufacturing or delivering a controlled substance.

At the time, Williams had been on parole for less than a year following a conviction for heroin possession. He said he believes this is why the officers targeted him to be an informant or face a return to prison.

After a year in jail, Williams went to trial. In court, Ugarte and two other officers testified that they had purchased heroin from Williams. But there were no other witnesses or evidence, according to the lawsuit. The jury acquitted Williams.

While in jail, Williams lost his personal assistant job with the Chicago Department of Human Services and dropped out of Strayer University, where he was pursuing a degree in business administration. “They took all that away from me because I wouldn’t work for them. I wouldn’t be a snitch,” he said.

In 2018, he filed a lawsuit in federal court alleging that Ugarte and the five other officers and their supervisor had violated his civil rights through unlawful search and seizure, excessive force and malicious prosecution. “I don’t think they really understand how hard it is coming from that place, coming out of prison,” he said.

After more than two years of hearings and lengthy court filings, the city settled the case in 2020 for $85,000, but denied any wrongdoing.

In records provided to The Post, Chicago officials had not recorded Ugarte’s name with Williams’s settlement. The Post identified him as an officer involved in the case through Williams’s attorney, the amount and date of the payment and court records.

Williams’s attorney, Torreya L. Hamilton, said the case was the second one she had handled involving Ugarte. In 2017, the city paid $88,500 to a man she represented who also alleged that Ugarte wrongfully arrested him and was part of a team of officers that fatally shot a dog in front of a 12-year-old child.

“This same team of officers was busting into people’s homes and killing dogs. In front of kids,” said Hamilton, who began her career as a prosecutor and now focuses on police misconduct and whistleblower cases. In the past five years, Hamilton said 95 percent of her clients who have sued Chicago police for excessive force or wrongful arrests have been Black or Hispanic.

“Why are they still working?” Williams asked. “There’s no punishment. They can do what they want. There are no repercussions behind it.”

The Post’s analysis found Chicago had the highest rate of misconduct claims involving officers named in multiple cases. More than 70 percent of the city’s roughly 1,500 payments over the decade involved at least one officer with repeated claims.

Ugarte, 47, was “relieved of police powers” in October and reassigned to the department’s alternative response section, according to Anthony Spicuzza, a police spokesman. The division handles non-emergency calls. Spicuzza declined to answer questions about Ugarte’s work or the payments involving him. Ugarte joined the force in 2005, according to the Citizens Police Data Project, a Chicago-based nonprofit that tracks information about officers, including use of force, complaints and awards.

Ugarte did not return a Post reporter’s calls. Spicuzza did not respond to requests for a response from Ugarte. “Due to a pending investigation, we will not comment further,” Spicuzza said.

Poor communication

In Detroit, after receiving questions from The Post about the repeated payments involving Officer Moore and the raid at Murray’s home, police officials said they have begun to use the city’s claims data to monitor which officers are repeatedly named in lawsuits, to determine if they need additional training or should be reassigned or removed from the force.

Christopher Graveline, director of the professional standards unit for Detroit police, said his department as of September is working closely with the city’s legal department to identify officers with more than two lawsuits or claims and make sure they are “flagged” in the department’s risk management system.

Since The Post started asking the city about its repeat officers in September, 13 officers have been “flagged” for being sued multiple times and have been subject to “risk assessments,” according to a department spokesman.

“There wasn’t a good communication between the city law and police department. We weren’t being aware of settlements and potential judicial findings touching upon our officers,” Graveline said.

Graveline, who oversees internal affairs, said the department was often unaware of findings in civil cases, including determinations that officers had withheld evidence.

From 2010 to 2020, Detroit made 491 payments on behalf of officers, totaling nearly $48 million, records show. More than half were on behalf of officers with more than one claim.

In addition to the 10 payments on claims involving Moore in that time, The Post also documented three before 2010 and one in 2021. During Moore’s 23 years on the force, Detroit paid 14 claims arising from his police work.

Moore was part of the city’s narcotics unit, a division that conducts many search warrants, Graveline said.

Graveline declined to comment on Moore’s lawsuits but acknowledged other officers in the unit were not named in as many lawsuits. “That’s one of the reasons we are taking steps to actively identify officers with similar patterns with multiple lawsuits,” he said.

During a deposition in the lawsuit following the search of Murray’s home, Moore testified that he had always intended to raid that residence. He said the wrong address on the warrant was a typo.

Moore said an informant told him about drug dealing at Murray’s home. Moore also noted in his report that police found two tiny bags of marijuana during their search, which Murray disputes.

In a separate report, one of Moore’s colleagues wrote that he shot Murray’s Labrador because the dog charged them and was “showing teeth and growling.” Also in the report, the officer misidentified Murray’s dog as a “grey pit bull.”

“We are not just going into these houses killing people’s dogs for no reason. That would be ridiculous and absurd,” said Moore, who was in the house when his fellow officers killed Keno. “Unfortunately, I’ve killed quite a few dogs. I would say I’ve killed over 10, 15 animals in the course of my career.”

In response to questions from Murray’s attorney, Kenneth Finegood, Moore testified that while he was with the drug unit, he had been the subject of internal investigations “once or twice a month.” Moore, 49, also said he had never been found guilty of the accusations, which he said happened “constantly” when he was in narcotics.

Personnel records obtained through a public records request show Moore joined the department in 1996 and has received seven awards or commendations.

The records also show that Moore was reprimanded for failing to fill out a use-of-force report during a 2010 arrest and was suspended for five days for “willful disobedience of rules or orders” during a 2015 police chase. An investigation determined that Moore failed to notify the dispatcher of the initial traffic stop and then failed to broadcast the speed of the vehicle being pursued. The suspension was later overturned in arbitration.

Moore left Detroit in 2019 and is now an officer at the nearby Oakland County Sheriff’s Department, according to Detroit police and the sheriff’s department. The sheriff’s department did not answer follow-up questions.

Since Moore’s departure from Detroit, allegations about his conduct when he was an officer have continued to cost the city financially.

Last year, Detroit officials settled a man’s claim that Moore and three other officers tackled and injured him in 2016 as he stood on his front porch. Police said they were searching for a shooter who allegedly fit his description, according to the lawsuit. The city settled for $150,000.

Detroit reached a second settlement concerning Moore in 2020 when the city paid $10,000 to resolve a claim by two men who alleged that Moore and other officers illegally handcuffed and searched them in 2016.

During the encounter, Moore and his colleagues confiscated $579 from one of the men, according to the complaint.

Moore wrote he searched the man and found six Baggies of a “leaflike substance.” Police arrested the man on drug-related charges and towed his friend’s car.

The car’s owner had to pay $350 to retrieve his vehicle from the impound lot, the suit alleged.

In addition to the drug charge — which was later dropped — Moore gave the man a citation for loitering, a misdemeanor offense. Moore wrote the man was in a “known narcotics location.”

The man, according to the lawsuit, was standing in the driveway of his home.

Alice Crites, Nate Jones, Jennifer Jenkins and Monika Mathur contributed to this report.

About this story

Editing by David Fallis, Meghan Hoyer and Sarah Childress. Graphics by Leslie Shapiro and Joe Fox. Graphics editing by Danielle Rindler. Design and development by Jake Crump and Tara McCarty. Design editing by Christian Font. Photo editing by Robert Miller. Video by Joy Sharon Yi, Jayne Orenstein and Jackie Lay. Video editing by Jayne Orenstein and Tom LeGro. Copy editing by Mike Cirelli and Wayne Lockwood. Produced by Julie Vitkovskaya.

Methodology

To investigate how often payments were madeon claims of misconduct repeatedlyinvolving the same officers, The Washington Post filed public records requests with 50 of the largest city and county law enforcement agencies in the nation. The Post sought information on civil lawsuits and liability claims that resulted in payments between 2010 and 2020 and requested the names of the officers involved in those claims.

The Post obtained data for 25 of these departments from multiple sources: in some cases, financial departments; in others, law departments, legal counsel or the police department itself. Reporters then standardized and cleaned the data, identifying gaps in what was provided. Seventeen of the cities or countiesdid not provide the names of officers involved. New York City provided officer names in only a small percentage of cases.

Claims that did not resultin lawsuits represent a very small portion of thosedocumented. The Post relied on city and county agencies to provide officer names in those cases and most provided those names.

The Post also supplemented its data with other sources.

For Chicago, reporters used data compiled by the Chicago Reporter on police settlements from 2011 through 2017 to find officers named in the claims data the city provided to The Post, and then retrieved names in additional cases from 2010 and 2018 through 2020.

In Baltimore, officials directed The Post to the city’s Board of Estimates website, where reporters downloaded the text of all meeting minutes that mentioned police settlements. The Post compiled a database of cases from that, and looked up cases in the court system to find officers’ names.

In New York City, officialsdid not provide the names of officers involved in more than 30,000 cases; reporters used payment data since 2013 provided on the law department’s website to identify officers, and then retrieved names from pre-2013 claims from court cases.

Phoenix was the only city for which The Post was unable to identify the officers involved. Officials there did not provide officer data or enough information for reporters to confidently match claim amounts with court records.

In thousands of cases, the city, county or court records identified officers only as “John Doe,” “Jane Doe” or unknown, and The Post was unable to determine those identities. For the analysis of officers who were the subject of repeated payments, The Post did not count those claims. However, claims involving the unknown officers were included in the total claim amounts and counts for each department.

For the analysis, The Post also excluded the names of most senior officials at the departments. Most of the people removed were police chiefs, but a supervisor in the District was omitted from the analysis because he was named in 19 cases related to his police unit but the complaints did not directly involve him.

The Post excluded payments of less than $1,000, which helped to standardize data across departments based on variations in what was provided. Reporters also sought to remove internal legal fees from the analysis in the few places, including Portland, Ore., that provided them.

All claims were grouped into broader categories for analysis and presentation using the information provided by cities and counties. In cases for which they did not provide categorization, those claims were categorized as “Unclassified Allegations of Misconduct.”

The Post reached out to every department and city or county officials who provided the data multiple times for comment. At each department, the three officers or deputies involved in the most settlements were also asked for comment. The Post incorporated any comment from departments and officers on its published interactive.

Payments are based on allegations of misconduct by police, but departments rarely admit wrongdoing when resolving these cases.

Keith L. Alexander covers crime and courts, specifically D.C. Superior Court cases, for The Washington Post. Alexander was part of the Pulitzer Prize-winning team that investigated fatal police shootings across the nation in 2015. He joined The Post in 2001. He previously worked as a reporter for USA Today, BusinessWeek and The Dayton Daily News.

Steven Rich is the database editor for investigations at The Washington Post. While at The Post, he has worked on investigations involving the National Security Agency, police shootings, tax liens and civil forfeiture. He was a reporter on two teams to win Pulitzer Prizes, for public service in 2014 and national reporting in 2016.

Hannah Thacker is a copy aide at The Washington Post. Before joining The Post, Thacker worked at the National Journal, Freakonomics Radio and the GW Hatchet at George Washington University. While at The Post, Thacker has worked within news operations, the investigations department and the news product department.

Democracy Dies in Darkness

© 1996-2020 The Washington Post