The U.S. atomic bomb attack on the people of Hiroshima at 8:15 a.m. on August 6, 1945, and the second attack on the city of Nagasaki at 11:02 a.m. on August 9 killed and wounded hundreds of thousands of unsuspecting men, women, and children in a horrible blast of fire and radiation, followed by deadly fallout. In years that followed, those who survived—the hibakusha—suffered from the trauma of the experience and from the long-term effects of their exposure to radiation from the weapons.

Historians now largely agree that the United States need not have dropped bombs to avoid an invasion of Japan and bring an end to World War II. President Harry Truman and his advisers were aware of the alternatives, but Truman chose to authorize the use of the atomic bombs in part to further the U.S. government’s postwar geostrategic aims.1

The bombings helped to launch the dangerous, decades-long U.S.-Soviet nuclear arms race; and they ignited a debate about the dangers of nuclear weapons, their role in foreign and military policy, their regulation and control, and the morality and legality of their possession and use that continues to this day.

Although nuclear weapons have not been used in a military attack since 1945, they have left a trail of devastation, including cancer from atmospheric nuclear test fallout, toxic waste and environmental contamination, and workers and residents exposed to radiation and hazardous chemicals from nuclear weapons production plants, uranium mines, and research labs.2 All too often, indigenous and disempowered communities have found themselves downwind and downstream.

Beginning with the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, when U.S. authorities sought to censor information about nuclear weapons, the nuclear weapons establishments have tried to hide and stifle debate about the health and environmental effects of nuclear war and nuclear weapons development, testing, and production.

In 1956, however, the Japanese survivors of the atomic bombings came together and pledged to work to “save humanity from its crisis through the lessons learned from our experiences” and issued their first formal appeal to the world that “there should never be another [h]ibakusha.”

The voices, testimony, and outreach of the hibakusha have been central to the decades-long struggle to put in place meaningful, verifiable, legally binding restraints on nuclear weapons; to realize a global treaty prohibiting their possession and use; and to advance the steps necessary to achieve the peace and security of a world free of nuclear weapons.

Through the decades, persistent citizen pressure and hard-nosed disarmament and nonproliferation diplomacy have produced agreements and treaties that have successfully curbed the spread of nuclear weapons, slowed the arms race, and reduced the danger of nuclear war. These initiatives slashed the staggering size of the Cold War-era U.S. and Russian arsenals, prohibited nuclear test explosions, and strengthened the taboo against nuclear weapons possession and use.

Yet, far too many of these weapons still exist. Combined, the U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenals total some 12,170 nuclear weapons, more than 90 percent of the global total, which is estimated to be 13,400.3 In addition to the United States and Russia, there are now seven more nuclear-armed nations, with smaller but still very deadly arsenals: the United Kingdom, France, China, Israel, India, Pakistan, and North Korea.

In addition, many of the dangerous policies developed over the years to justify the possession and potential use of nuclear weapons persist. For instance, the United States, Russia, France, and the UK maintain significant numbers of their nuclear weapons on prompt-launch status, ready to retaliate in response to a nuclear attack. The United States and Russia also cling to the option to use nuclear weapons first and against significant non-nuclear threats.

Making matters worse, the dialogue on disarmament has stalled. Tensions between many of the world’s nuclear-armed states are rising, and the risk of nuclear use is growing. The Trump administration has severely undermined U.S. credibility and capability to provide effective global leadership on nonproliferation and disarmament.

The world’s nine nuclear actors are squandering tens of billions of dollars each year to maintain and upgrade nuclear arsenals, monies that could be redirected to address real human needs. The United States and Russia have discarded or disrespected key agreements that have kept their nuclear competition in check, and other agreements are in jeopardy. Other nuclear-armed states, for the most part, still remain outside the nuclear risk reduction and disarmament enterprise. We are once again on the verge of a new, global nuclear arms race.

Our nuclear anxieties persist, and humanity’s efforts to contain and eliminate the nuclear weapons danger continue.

The historic 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which has won the support of the vast majority of the world’s non-nuclear states, is a step forward, but the current environment necessitates even bolder action from civil society and governments everywhere. We must reduce nuclear risks, and we must freeze, reverse, and ultimately eliminate nuclear weapons.

The survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings bear witness to the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons. As the authors of a new 2020 appeal from a consortium of hibakusha leaders and organizations write, “The average age of the [h]ibakusha now exceeds 80. It is our strong desire to achieve a nuclear weapon-free world in our lifetime, so that succeeding generations of people will not see hell on earth ever again.”

Arms Control Today presents the following annotated photo essay to honor their call to action.

ENDNOTES

1. J. Samuel Walker, “The Decision to Use the Bomb: A Historiographical Update,” in Hiroshima in History and Memory, ed. Michael J. Hogan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

2. Arjun Makhijani, “A Readiness to Harm: The Health Effects of Nuclear Weapons Complexes,” Arms Control Today, July/August 2005. See Arjun Makhijani, Howard Hu, and Katherine Yih, eds., Nuclear Wastelands: A Global Guide to Nuclear Weapons Production and Its Health and Environmental Effects (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000).

3. Hans M. Kristensen and Matt Korda, “Status of World Nuclear Forces,” Federation of American Scientists, April 2020, https://fas.org/issues/nuclear-weapons/status-world-nuclear-forces/.

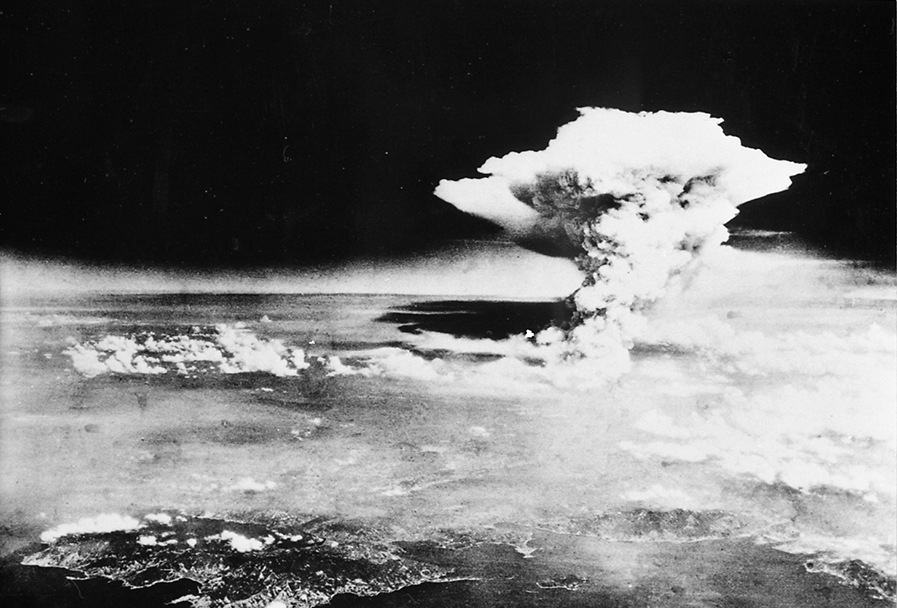

The cloud generated by “Little Boy,” the uranium-based atomic bomb dropped by the United States on Hiroshima, rises above the city with a wartime population of approximately 320,000 on the morning of August 6, 1945. The blast packed a destructive force equivalent to about 15 kilotons of TNT. In minutes, approximately half of the city vanished. (Photo: Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum)

Three days later, the city of Nagasaki burns following the decision by U.S. leaders to drop “Fat Man,” a plutonium-based bomb with an explosive yield estimated at 21 kilotons, on the city of approximately 260,000 at the time of the attack. (Photo: UN/Nagasaki International Cultural Hall)

The Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall stands alone in the rubble. The explosion produced a supersonic shock wave followed by extreme winds that remained above hurricane force more than three kilometers from the hypocenter. A secondary and equally devastating reverse wind ensued, flattening and severely damaging homes and buildings several kilometers further away. Only remnants of a few reinforced structures remained. (Photo: Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum)

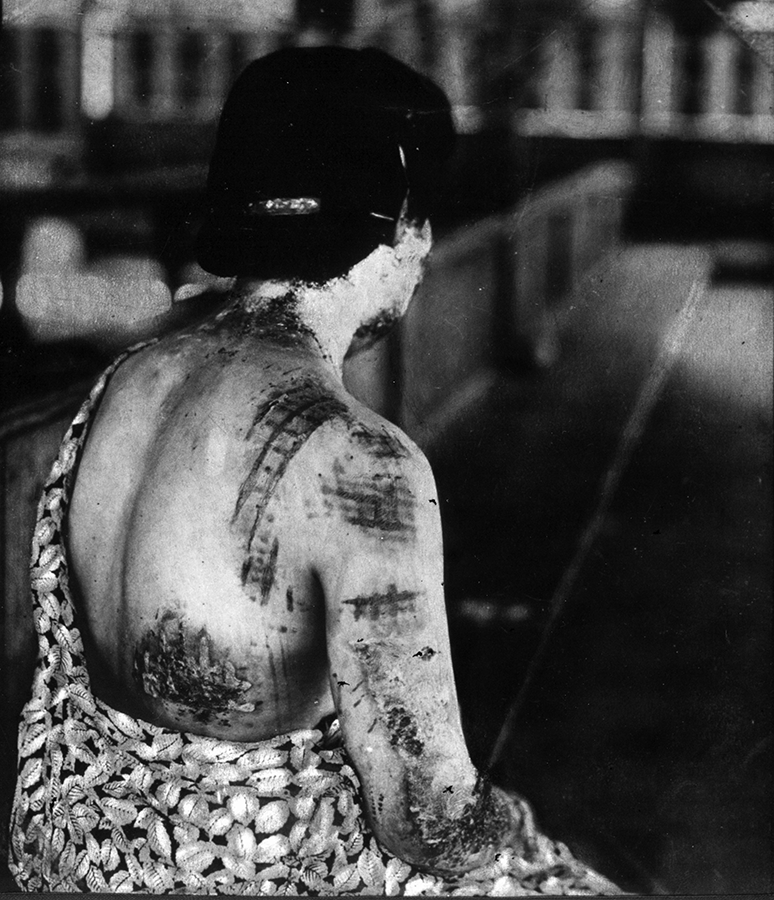

A burned body in the ruins 500 meters from the hypocenter; and the pattern of a woman’s kimono burned into her skin. The intense heat rays of the Hiroshima bomb reached several million degrees Celsius at the hypocenter and incinerated everything within approximately two kilometers. The heat scorched flesh and ignited trees and other flammable materials as far as 3.5 kilometers from ground zero. Flash burns from the primary heatwave caused most of the deaths at Hiroshima. By the end of 1945, an estimated 140,000 were killed by the blast, heat, and radiation effects of the nuclear attack. (Photo: Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum)

The city of Hiroshima on fire on August 6, as seen from four kilometers away. A firestorm ravaged the city of Hiroshima for hours after the explosion, peaking around midday. Firestorms leveled neighborhoods where the blast had inflicted only partial damage and killed victims trapped under fallen debris. Within 20 minutes, the explosion also produced black rain laden with radioactive soot and dust that contaminated areas as far away as 29 kilometers from ground zero. (Photo: Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum)

The ruins of Nagasaki on August 10, 1945, at about 700 meters from the hypocenter. The nuclear attack on Nagasaki killed an estimated 74,000 by the end of 1945 and injured approximately another 75,000. The attack occurred two days earlier than planned, 10 hours after the Soviets entered the war against Japan, and as Japanese leaders were contemplating surrender. (Photo: UN/Yosuke Yamahata)

The remains of a religious temple in Nagasaki on September 24, 1945, six weeks after the bombing. Many of those who survived the Hiroshima and Nagasaki attacks would die in radiation-induced illnesses years later. The number of survivors contracting leukemia increased noticeably five to six years after the bombing. Ten years after the bombing, the survivors began contracting thyroid, breast, lung, and other cancers at higher than normal rates. These hibakusha and their descendants helped form the nucleus of the Japanese and global nuclear disarmament movement. (Photo: Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Images)