Naming the void left by the Holocaust is not only a moral duty but also the only way for us, as survivors, to maintain our own humanity.

In a scene in Claude Lanzmann’s groundbreaking documentary Shoah, historian Raul Hilberg, a giant in the world of Holocaust research, sits in his study in a wintry Vermont. He has a piece of paper in his hand: a typical traffic order, a Fahrplananordnung, with number 587, he explains, regarding a train transport to Treblinka. The abbreviation PKR appears, which denotes full trains, and also the letter L which stands for Leer, which means empty. It appears that this train consisted of 50 wagons and was heavily loaded when it arrived at Treblinka at 11:24 on Oct. 1, 1942 and that it departed four and a half hours later, empty and tidy. The train was driven to a city where a ghetto had been emptied to retrieve its new human load, which it deposited in Treblinka the following day. All is evident from this traffic order, this form, a trivial document. And yet it is a paper that involves the death of ten thousand people. Raul Hilberg counted.

In the film, Claude Lanzmann cannot reconcile the triviality of the paper and its deadly consequences. I’ve been to Treblinka, he says, and to bring these two together, the death camp and this document… Then Hilberg replies: “When I get hold of a paper of this kind, especially as it is an original document, I know that the bureaucrat of the time himself held it in his hands. It’s an artifact, and that’s all that’s left. The dead are no longer there. ”

These simple words summarize the situation for all of us living after the genocide of the European Jews. People were murdered, their bodies burned or thrown into hollows in the ground. Their homes and businesses were stolen, their watches stolen, their clothes sold on, their hair cut off and used to fill German soldiers’ mattresses. They were literally erased from the face of the earth.

We are left with a void. It harbors people who called themselves atheists and Jews, assimilated and orthodox, baptized and converted Christians, Sinti and Roma, homosexuals, those who had been classified insane. An insatiable amount of thoughts, songs, prayers, debates, tenderness and laughter was erased.

But how to understand what does not exist? The fact that a loved one dies, simply ceases to be, can be difficult enough to comprehend. How to fathom the absence of millions of murdered people? This void is part of our present world — it is common history, it influences politics, the writing of history and even how the physical world looks. Anyone passing Bebelplatz, in the middle of Berlin, can see an inverted library created by the Israeli sculptor Misha Ullman. In the exact place where 30,000 books were burnt, there is now a glass plate where you can look down into an underground room — white as death — with empty bookshelves, a storage place for everything that no longer exists.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Fragments like the traffic order in Shoah are so important because they escaped this void, and can tell the story of that time. But sometimes, as was the case for me, they are easy to miss. In January of 2010, a woman named Eva Ullman, the daughter of Otto Ullmann, a Jewish refugee child who was sent to Sweden to escape Nazi persecution, approached me after reading one of my books. She told me that her father was born and raised in a middle-class family in Vienna, a beloved and strong-willed child who loved music and football. When Hitler annexed Austria in March 1938, he was 12. His family managed to get him to Sweden in early spring 1939. The plan was to join him later, but until that became possible, they would write him a letter a day.

Eva had those letters. There they were, more than 500 letters from Otto’s parents, with the profile of Hitler on the stamps, straight out of the void. After her father died, she had never opened them, but never forgotten them either. As the daughter of a Holocaust survivor, she grew up learning that there were some areas not to be tread on, some words not to be uttered, and some questions never to be asked. The letters were placed in an IKEA box in her closet, lid on, until she got the idea of offering them to me.

I said thank you, but no thank you. The letters were of course written in German, a language of which I had little knowledge, but that wasn’t the main reason. I simply couldn’t stand the idea of writing about the Holocaust. The unbreakable silence within the Ullmann family was all too recognizable, it existed also within my family. And so we said goodbye.

But then, night after night, before going to sleep, I found myself imagining the letters going from Vienna to the south of Sweden, one a day, from a parent to a child. The image just wouldn’t leave me alone.

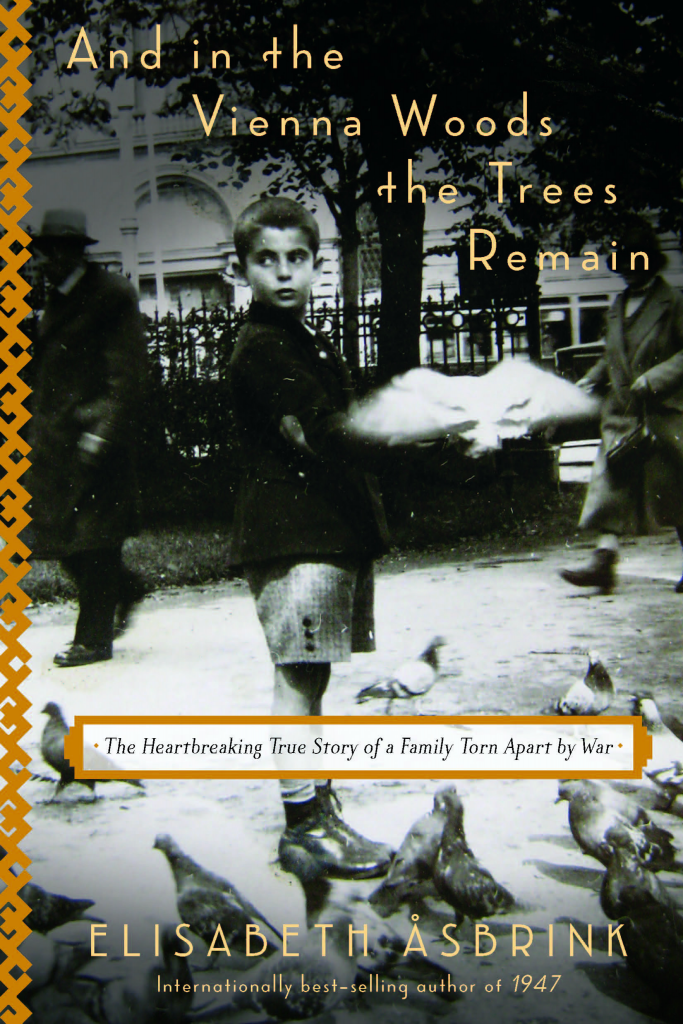

The result is And in the Vienna Woods, the Trees Remain, a story about a boy and his parents, an attempt to make the void visible. And within the story is another: In early 1944, after leaving the Swedish orphanage where he first ended up, Otto Ullmann applied for a job at the Kamprad estate in Småland and became best friends with the son of the landowner, Ingvar. Later, when Ingvar Kamprad decided to create the furniture company IKEA, Otto was his number one man and sidekick for a decade.

Ingvar Kamprad let me interview him (the result is in the book). But when I found the files from 1943 in the Swedish Secret Police Archive, stating he was member 4014 in Swedish Socialist Unity (Svensk Socialistisk Samling, or SSS), the Swedish Nazi party at the time, he declined any further contact.

And the letters? They are still, ironically, in that IKEA box, waiting for transfer to an archive where they will be made available to researchers.

The millions of Jews murdered in the European genocide were not only deprived of their lives and their futures — they were also deprived of their deaths: the deaths that occur in culture, in the rites, and that express each human being’s individual value; the deaths that form the ground of memory.

Naming the great European void, recognizing its existence by remembering, is thus not only a moral duty but also the only way for us, as survivors, to maintain our own humanity. When all that escapes the void are pieces of paper, those documents are anything but trivial. They are the instruments of memory.

Elisabeth Åsbrink is the author most recently of And in the Vienna Woods the Trees Remain: The Heartbreaking True Story of a Family Torn Apart by War, recently published by Other Press.