In the four decades since the Islamic Revolution, Iranian artists have used clever tactics and unconventional modes of art-making to display disobedience.

Recent weeks have seen a surge of protest art in Iran, triggered by the tragic story of Mahsa Amini, a young woman killed on September 16 by the morality police for breaching the Islamic republic’s dress code for women. Since then, civil unrest has grown in more than 80 Iranian cities, with calls for justice as well as personal and political liberties, not to mention hundreds of arrests and violence against protesters, especially young women. Internet access remains limited as the government regulates its usage.

Amid these protests, artists have played an important role in bringing their message to the fore. Shervin Hajipour’s song (#Baray-e [For the sake of or Because of]), recorded in his room and posted on Instagram for limited followers, was shared more than 40 million times on social media platforms in just two days. Taken from #Baraye protest tweets, Hajipour utters the grievances and hopes of Iranians, with a final emphasis on “For Women, Life, Freedom,” the main slogan of recent protests.

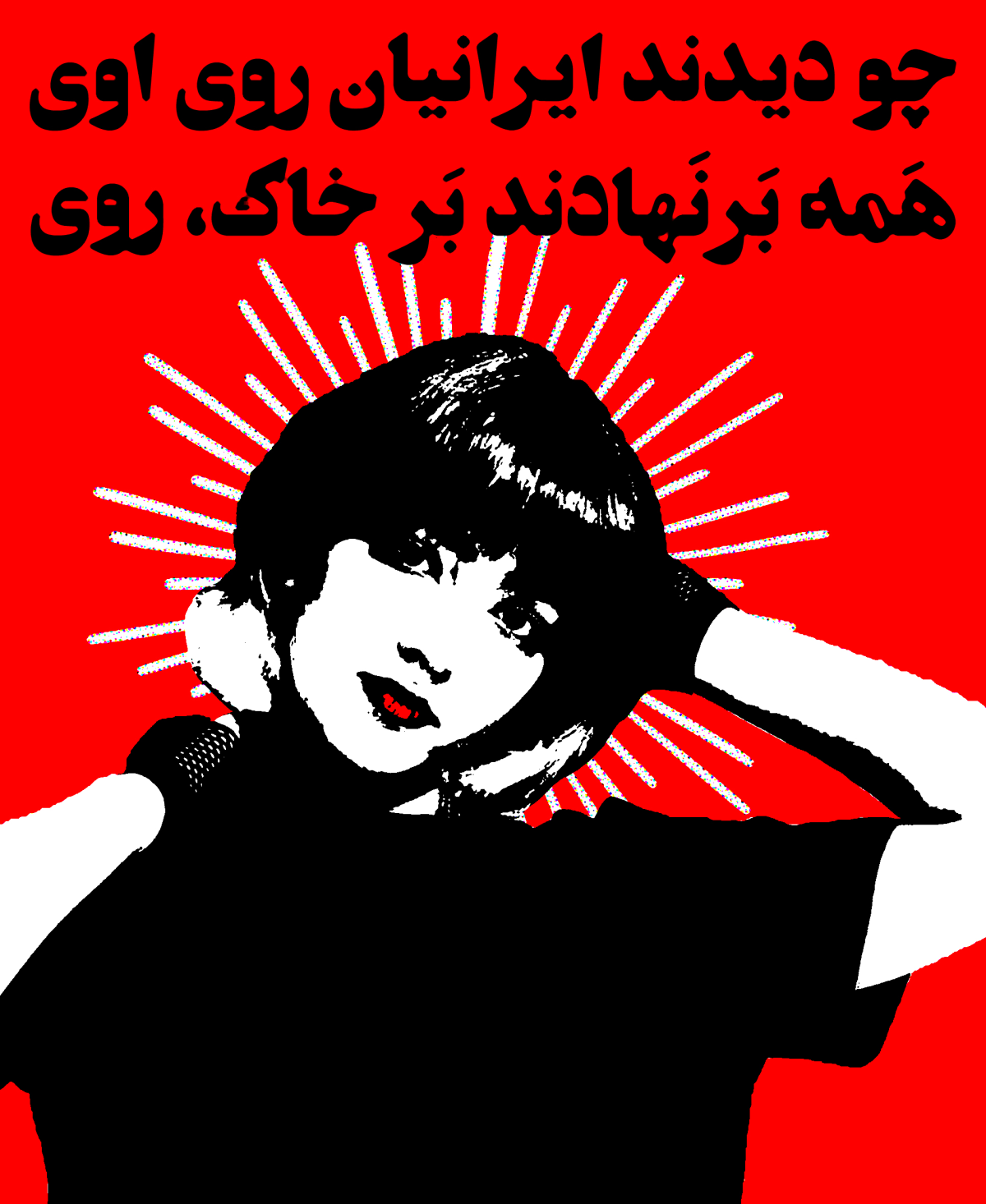

Art coming out of Iran (or by artists in the diaspora) has a radical and rebellious zeal, also evident in the visual arts. Consider, for example, the work of dozens of Iranian artists — many of whom are women — who have been featured by Hyperallergic and the Guardian. Brave works with layered meanings, they appropriate concepts and imagery from earlier periods, especially those familiar to Iranians. Meysam Azarzad’s posters shared via Instagram seem to have borrowed from revolutionary themes of earlier years — found in both leftist and Islamist factions that helped overthrow the Shah’s regime in 1979. Using red, white, and black, they also seem to align the recent uprising with the visual culture of other global revolutionary movements. A filmmaker with university training in graphic design, Azarzad refutes any link to Iran’s revolutionary posters, especially those with religious iconography. Juxtaposing bold black-and-white silhouettes of fighting and fallen young women with nationalistic poetry, Azarzad instead highlights their bravery in nationalistic terms. The content of the texts appearing above the women strikes a chord with rhyming couplets from the 11th-century epic Shahnameh (“Book of Kings”) by the patriotic poet Abul-Qasem Ferdowsi. One poster shows a defenseless young woman raising her fist — unveiled — to rows of soldiers. The couplet praises a hero, but the typical Shahnameh-style male hero’s name is replaced by “a fighting girl” (dokht-e jangi). The other posters draw our attention to the bravery of two 16-year-old girls. Appearing like saints, Nika Shahkarami and Sarina Esmailzadeh were both beaten to death during protests. The portraits are juxtaposed with poetic lamentations over the death of a heroine, again in the style of Shahnameh.

Most of these works were created by graphic designers and illustrators for social media platforms; however, they represent only one of the diverse art forms being produced in contemporary Iran. In response to the current unrest, many have abandoned exhibition and performance for the “anonymous” expression of political views through graffiti and ephemeral installations. In disguise, artists have placed slogans that challenge the country’s clerical leadership; in an ironic twist, many parody the revolutionary slogans of the Islamic republic. On October 7, an anonymous artist created “Tehran in Blood,” dyeing fountains in important cultural centers red. In response to an attack on demonstrators at Tehran’s Sharif University, two anonymous women artists animated trees in Daneshjoo (“University Student”) Park by hanging red nooses from branches. The police swiftly removed these installations, but their pictures persisted on social media platforms and even found their way into mainstream media.

For four decades, though, Iranian art’s defiance has been subdued. Compare two posters by graphic designer Pedram Harby. The one on the left, created for recent protests, is animated by a female mouth ostensibly shouting grievances. Appearing next to a #MahsaAmini hashtag, and between the confidently rendered words “Zan” (Woman) and “Zendegi, Azadi” (Life, Freedom), the work seems bold compared to an earlier poster designed by Harby for Unpermitted Whispers, a 35-minute play by the Iranian theatre director Azadeh Ganjeh staged four times a night in 2012 using ordinary taxis. For each performance, three actors were picked up and dropped off in sequence. The characters in the performance were iconic women in Shakespeare’s plays, such as Ophelia whose intense love, madness, and despair were personified in the character of a woman from contemporary Tehran who spoke of conflicts between ordinary Iranians and the police forces. Despite the play’s political tone, Harby’s poster remains understated. A red traffic light affixed to a Q-tip, the ensemble indicates the threats of being blocked and unheard.

Such indirect visual language has been the dominant visual idiom of Iranian art in the past four decades, because all art has to be sanctioned by an organization that works like the “morality police.” Commonly referred to as Vezarat-e ershad, or Ministry of Guidance (shorthand for the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, hereafter MCIG), the organization has censored the arts since the early 1980s. Iranian artists of all branches have had to improvise to flout this organization’s rules. While the MCIG has tried to suppress artistic expression, however, it has inadvertently pushed artists to be more inventive. Rather than self-censoring, artists have long employed clever tactics for presenting disobedience. While visual artists like Harby use subtle and perplexing iconography, performance artists, like Shahab Fotouhi, draw on what the German dramatist Bertolt Brecht calls Verfremdungseffekt (alienation), the theatrical device that intentionally distances viewers from the fictive narrative and instead engages them in real activities, such as mock performances that look like fully sanctioned political roundtables in Iran and yet somehow challenge the ideals and ideas of the regime.

In my book Alternative Iran, I highlight another important strategy: spatial tactics employed by artists of all genres as well as the curators and architects who team up with them. Such strategies include going literally underground along vertical blocs, even when MCIG permission is granted; distancing oneself from the “official” centers of art production and growing, instead, along horizontal axes; creating ephemeral installations; deploying spatial camouflage; and negotiating the limits of the permitted and the forbidden by manipulating art venues or gallery spaces. Using these spatial strategies, artists have flouted MCIG laws, showcasing politically sensitive art without getting into trouble.

Restrictions imposed by the MCIG have also given form to unconventional modes of art-making, not meant for official venues. Instead, these art forms appear in derelict buildings, leftover urban zones, and remote natural sites. Following the Iran-Iraq War (1980–88) and starting in the 1990s, a few exhibitions in rundown and ready-to-renovate homes (kolangi) revived forms of conceptual art (honar-e mafhoomi), performance art (honar-e ejra’ie), and ephemeral art (honar-e mira). Many works were site-oriented rather than site-referenced or site-specific; that is, the site’s shape, history, socioeconomic conditions, and sociopolitical connotations were less important than the fact that the location provided opportunities for freedom of expression that were unavailable in conventional art spaces. However, on the eve of former Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s election in 2006 and the imposition of further restrictions on journalists, the abandoned headquarters of the most prominent state-run newspaper, Ettela’at, became a platform for a monumental installation by Farideh Shahsavarani.

Titled I Wrote, You Read, Shahsavarani’s work commented on censorship of the journalistic freedom that had reached its peak after eight years under President Mohammad Khatami. Some newspaper pages were encased in barbed-wire stands; some covered the walls, windows, and ceilings; others appeared in videos accompanied by the sounds of typewriters and sirens. The exhibition also devoted a small room to the memory of journalists who had been arrested and detained. This Gesamtkunstwerk engaged multiple human senses, affirming a form of art viewing that depends not only on our eyes but also on our bodies. Shahsavarani, who did not secure permission from MCIG for her site-specific project, ended up taking it down after one week.

Another spatial technique used for the purpose of subduing protest art has been camouflaging. On August 5, 2013, when President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was sworn in for a second term, the police attacked crowds who had gathered outside parliament to protest, arresting many. Against such chaos, Ahmadinejad called for national unity and quoted from Article 121 of the Iranian constitution, vowing to dedicate himself “to serving the people and . . . spreading justice and refraining from any dictatorship.” Artist Katayoun Karami, who took part in the protest, was angered by these deceitful proclamations. Four years later, for the next election day, she created an installation with curator Rozita Sharafjahan at Tehran’s Azad Art Gallery. Titled Good Thoughts, Good Words, Good Deeds, an ancient Zoroastrian motto, the project “trapped” visitors as they explored the gallery. Karami had laser-cut the words of Article 121 from mats coated with adhesive from rat traps. The mats covered the floor so visitors could not escape the sticky mess; this was a metaphor “for always being caught in the political predicaments,” Karami reminded. At first, the words were hardly visible to the visitors and the MCIG staff who issued permission; however, after many visits, the sticky pads became dark and decipherable. The visitors, in turn, reluctantly carried home some adhesive on their shoes. Karami, who is from a generation that has seen it all (i.e., the revolution, Iran-Iraq war, Green Movement), believes that engaging visitors’ bodies conveyed the collective discontent with Iran’s political system.

Another prominent artist in the category of camouflage is Pooya Aryanpour, who has been using the trick to subtly tease social and political restrictions within Iran. Relying on traditional mirrorworks, his art ironically exudes a religious air. Mirrorworks are used in Shi‘ite shrines of Iran, covering entire walls, arches, vaults, and ceilings with fragments of mirrors so fractured that one’s reflection is skewed, with an urgency drawn from the teachings of the highest-ranking Shi‘ite clerics that proscribe praying in front of portraits, including one’s own image. Noteworthy among Aryanpour’s camouflaged projects is a 2022 installation of a suspended fabric-like structure whose surface is animated by mirrorwork. Executed in collaboration with curator Maryam Majd and Dastan Gallery, Gone with the Wind hangs in the dark, alluding to several cultural signifiers, from the black banners that commemorate a religious holiday or death of an imam or martyr to the ideal veiling for women, the black chador. The site was an abandoned sugar factory in Kahrizak, a formerly booming industrial area in southern Tehran. The choice for the site, Aryanpour explains, was tied to the work’s meaning — signifying the dark and bright aspects of the Islamic republic at once. Once a site of production, the factory is now nothing more than a vacated space left to decay, a metaphor for the country as a whole. On the Dastan Gallery website, a text by Majd describes it as “beautiful, yet lost,” and that which “directly makes references to us and our lives”, amounting to an “aesthetic allusion” to the “incomplete, contradictory, and unstable situation[s] experienced” by the Iranian people.

The few examples of art with tacit political messages presented here attest to a lineage of subtle strategies since the post-revolutionary period that has allowed artists to defy the MCIG. In other words, the recent protest art was set in motion earlier than this September. Indeed, oppositional voices escalated with the election of hardliner President Ebrahim Raisi and the new regulations enacted by his cabinet. In August 2021, when Mohammad Mehdi Esmaili, the newly appointed minister of Culture and Islamic Guidance under President Raisi, issued a new “program” (barnameh) for revamping MCIG’s rubrics to further “Islamicize” the arts, every faction of the arts community published open statements scrutinizing the new “program.” On Instagram, artist Alireza Amirhajebi wrote: “So far, we have shown elasticity (en’etaf) as much as we could. But now it is time for disobedience (sarpichi)….” Thus what we see today is a continuation of what surfaced after a near decade of relative flexibility under President Hassan Rouhani. The brave language of art today, which goes as far as challenging the supreme leader himself, will undoubtedly set a new tone for Iranian art in the months and years to come.