In a year that has brought profound change to to much of the world, the conflict-ravaged Middle East appeared to be finally turning a page. A diplomatic spree that sought to patch up long rifts bore fruit. Iraq transformed from the region’s epicenter of violence to one of progress, for example, brokering rare talks between old rivals Saudi Arabia and Iran.

Emerging from the crushing blows of the pandemic and four years of global turbulence during the presidency of Donald Trump, many of the Middle East’s nationshave shown signs that this level of conflict simply cannot go on.

But as the year grinds to an end, and as a whirlwind of diplomacy picks up speed, another geopolitical fault-line has appeared — the Middle East has become a political and economic battleground for the US and China, despite its continuous attempts to keep out of this powerhouse rivalry.

In comments that show just how anxious this is making the Middle East’s leaders,a high-level Emirati official earlier this month expressed a sense of hopelessness over the showdown between the US and China.

“What we are worried about is this fine line between acute competition, and a new Cold War,” Anwar Gargash, diplomatic adviser to the UAE leadership, said in remarks to the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington last week.

“Because I think we, as a small state, will be affected negatively by this, but will not have the ability in any way to affect this competition, even positively really.”

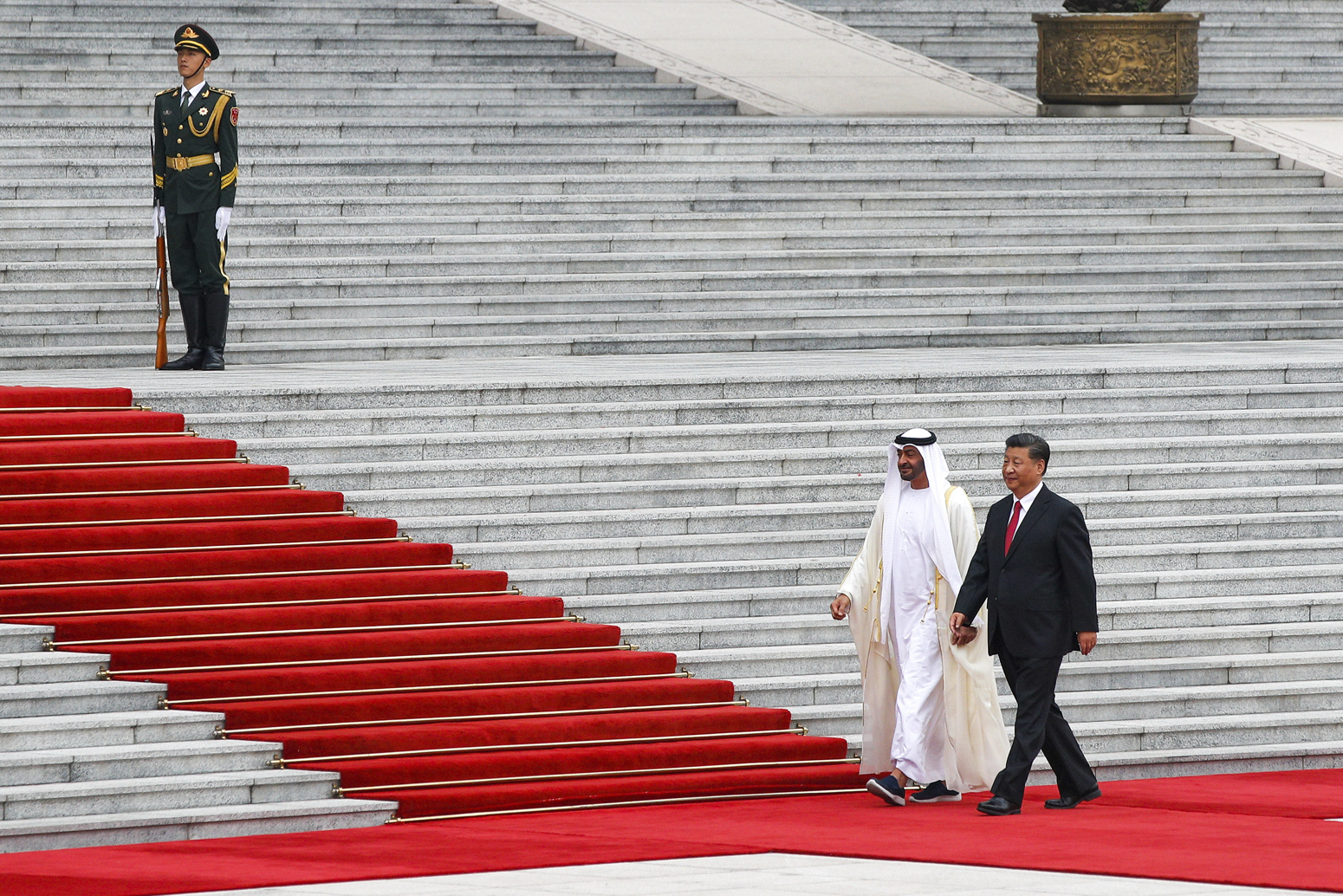

Gargash confirmed reports that the UAE — a key regional US ally — had shuttered a Chinese facility over US allegations that the site was being used as a military base. He made clear that Abu Dhabi was merely paying lip service to US intelligence — the UAE didn’t actuallyagree with Washington’s characterization of the site. Abu Dhabi simply did not want to upset a strategic ally.

CNN has reached out to China’s foreign ministry for comment.

But the US won’t always win the battle for influence in the country.Days after Gargash’s remarks, Abu Dhabi apparently decided to stop humoring America. It was suspending a multi-billion dollar purchase of US-made F-35 aircraft, the first deal of its kind with an Arab country. The US had made thesale conditional on the UAE dropping China’s Huawei Technologies Co. from its telecommunications network. Washington claimed the technology posed a security risk for its weapons systems, especially for an aircraft the US dubs its “crown jewel.”

Abu Dhabi disagrees. An Emirati official said a “cost/benefit analysis” was behind their decision to stick with Huawei at the expense of the F-35s. And while US officials have tried to downplay the significance of the event and insists that the sale has not been killed, Abu Dhabi had set a new tone Abu Dhabi does not intend to always bow to US demands over China, and it is dismissing Washington’s notions about Chinese trade deals disguised as covert military activity.

It’s an event could set the stage, not just for the Gulf powerhouse, but for an entire region where China’s rapidly growing trade relationships transcend oldgeopolitical rivalries, and where the US’ long-running hegemony could be coming to an end.

‘A theater of competition’

The Middle East has been rocked by geopolitical tensions arguably since Western colonial powers carved the resource-rich region into spheres of influence over a century ago.

But the region had rarely seen violence on the scale of the 2010s, when simultaneous wars in four different countries — Syria, Yemen, Libya and Iraq — as well as long-running violence in Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories, turned vast swathes of the Arab world into a bloodbath.

It was a period that coincided with a momentous political shift — the US was deprioritizing the Middle East as it became laser-focused on China. The subsequent chaos was unprecedented and appeared to anticipate a major power vacuum in Washington’s wake.

The flurry of regional diplomacy that came after — rushed and sometimes haphazard — also appeared to be hinged on a perceived US departure from the region. Throughout it all, China, once ideologically reviled by powerhouses like Saudi Arabia, was working in the Middle East’s shadows.

Beijing forged wide-ranging economic partnerships with the likes of Riyadh and Tehran. It deepened its foothold in economies that were already strong trading partners, such as the UAE, where it is on its way to becoming the fulcrum of its telecommunication networks.

Used to being targeted with accusations of human rights violations, Beijing promised to stay quiet on those in the Middle East, and to keep out of its conflicts. It has made the Middle East a key part of its Belt and Road Initiative, a massive infrastructural project that connects East Asia to Europe (Egypt’s Suez Canal is the project’s only maritime connection). And most of all, it presented an opportunity to hedge the region’s bets in the event of an American exit.

“You’ve got this scenario where this preponderant extra-regional power looks like it’s leaving and then you have China, a top trading partner,” said Jonathan Fulton, senior non-resident fellow at The Atlantic Council. “The region looks like a theater of competition. This looks like the way it’s going to play out.”

Analysts argue that if Washington forces the region to choose between the US and China, the answer will be a no-brainer — the US’ friends in the region are loath to draw the ire of the superpower, especially while its military presence in the Middle East remains expansive. But ultimately, the region may have no choice but to take the Chinese carrot even if it means subjecting itself to the American stick.

The region’s gravitation towards China, argues Fulton, is “the law of nature. That’s how it’s going probably going to be for the next century.”

US needs ‘real cash on the table’

The main weakness in the US’ proposition regarding China in the Middle East is that Washington offers no alternatives to Beijing’s lucrative deals.

The US can try to coerce the UAE, for example, to withdraw from its Huawei deal, but it is unwilling to give them a competitive second option. At the start of Lebanon’s financial tailspin in 2020, the US pressured Beirut to resist turning to Beijing for investments in Lebanon’s decaying infrastructure, with US Ambassador Dorothy Shea issuing televised warnings about the dangers of Chinese “debt traps.” The government of former Prime Minster Hassan Diab bowed to pressure, while the US largely spurned his government, which it believed to be backed by Hezbollah, and Western cooperation with the flailing economy has been little to none.

“US pressure has intensified in recent years, and especially since the start of the Belt and Road Initiative in 2013,” said Tin Hinane El Kadi, an associate fellow at the think tankChatham House. “However, in international politics, you can only pressure countries when you have substantive power and the means to really offer another deal.”

He added: “If the US really wants to pressure countries and win this so-called new cold war, it would have to move away from discursive play, and really start to put real projects, and some real cash on the table,”

Nor can the US claim the moral high-ground on human rights issues or on the espionage it accuses Chinese companies such as Huawei of conducting. Recent scandals around Facebook, for example, weakens that position, argued Fulton.

“We’ve been watching what Facebook does … and after (whistleblower Edward) Snowden … it’s hard for them to say you can trust us because we’re reliable,” said Fulton. “If we do it for liberal reasons and they do it for authoritarian reasons, it’s not really a case to make here.”

In the absence of a Western competitive alternative to Chinese cooperation, the writing appears to be on the wall. China’s roots in the region will only become deeper and are only set to rapidly expand. Countries that have been embroiled in largely wasteful conflicts will choose options that serve their economic interests. And as Abu Dhabi’s anxieties about being caught in the middle of rising tensions between larger powers has illustrated, the appetite for conflict is quickly dissipating.

“Even though the US right now, with very little leverage, is forcing countries to choose between the US and China, the fact that countries have more options, more loans that they can take from a variety of choices is a good thing,” Kadi said.

“Having more alternatives in the global scene can only be a good thing for the region and its stability.”