After the public got a newsreel glimpse of what the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki did to the Japanese, the footage lay dormant for more than two decades — shaping how the U.S. population processed the use of the weapon.

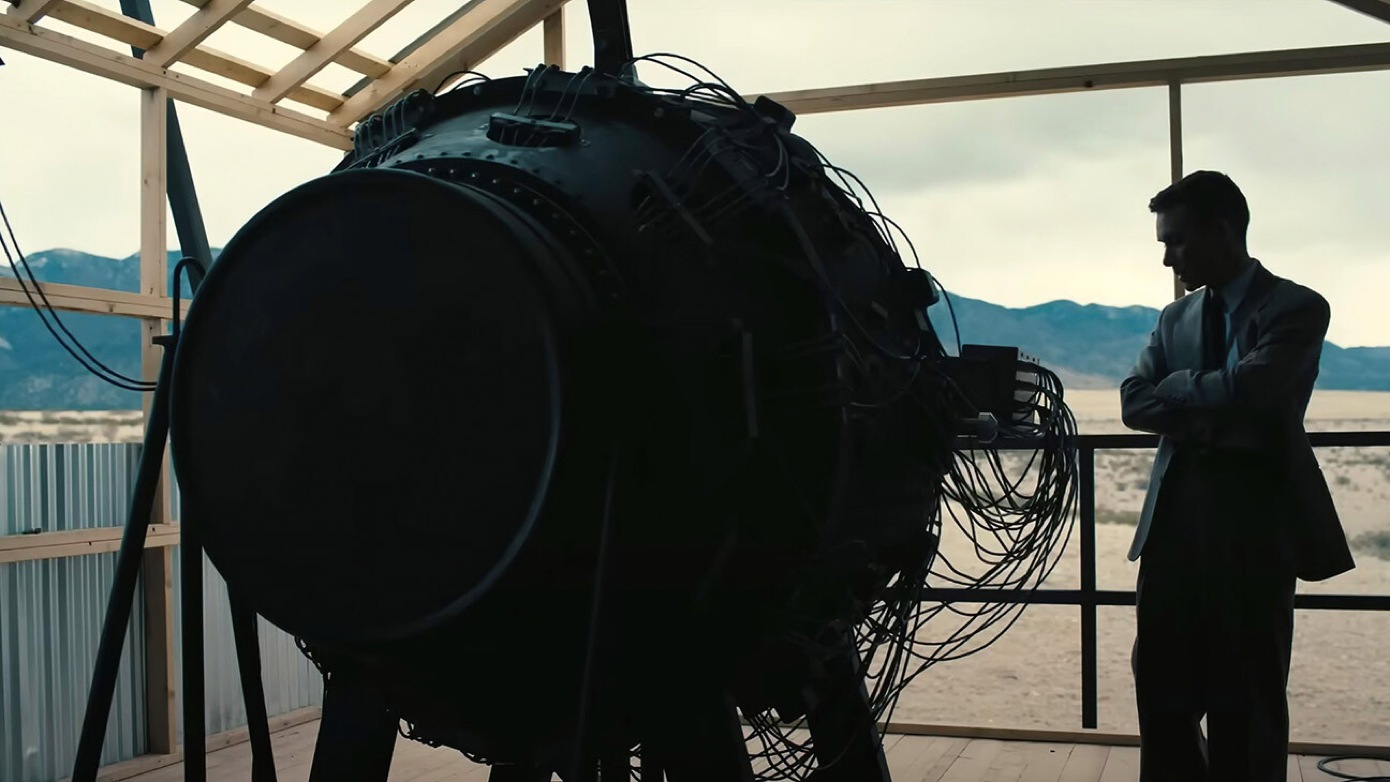

In the third act of Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb sits in a darkened hall and watches a slide show of what his gadget hath wrought at ground zero. From offscreen space, the lecturer clinically describes what we in the audience are spared from looking at.

The decision by director Christopher Nolan not to show the Japanese victims that should be in Oppenheimer’s field of vision has been both roundly criticized (Brandon Shimoda, curator of the Hiroshima Library, called it a “demoralizing” absence that “makes unreal the experience of Asian people”) and stoutly defended (in The Los Angeles Times, film critic Justin Chang responded, “omission is not erasure“).

Whatever your take, Nolan’s political/aesthetic choice presumes viewers are unspooling the pictures in their own mind. Compared to the newsreel record of the Holocaust, the visual imprint of the victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki has not been seared as indelibly into the popular imagination. For most of the Cold War, the motion picture evidence of the impact of atomic weaponry on humanity was memory-holed by squeamish media gatekeepers and restricted by the U.S. government. Only a few glimpses slipped through the cracks.

In 1945, Americans should have seen the victims of the atomic bombings in the newsreels, the screen journalism of the pre-television, pre-digital age. Throughout the classical Hollywood era, the newsreels were an integral part of what exhibitors called “the balanced program,” playing at the top of a film menu that included a cartoon, a comedy short, and a feature-length attraction. Five studio-affiliated newsreels released two issues per week, each running about eight to 10 minutes in length: MGM’s News of the Day, RKO’s Pathé News, Fox Movietone, Universal Newsreel and Paramount News.

When the atomic bombs were detonated over Hiroshima (Aug. 6, 1945) and Nagasaki (Aug. 9), newsreel editors were caught flatfooted. Of course, they were given no prior notice of the use of the top-secret weapon, but the military had prepared elaborate press releases for newspapers and radio (CBS broke in with a bulletin at 11:15 a.m. on Aug. 6, NBC two minutes later). The newsreels scrambled to play catch up. Camera crews descended on the sites revealed to have played the key roles in the Manhattan Project — Oak Ridge, Tennessee; Richland, Washington; and Los Alamos, New Mexico — but they were forbidden access by still-wary authorities. Not until Aug. 21, 1945, did the military provide some 80 feet of film (close to a minute) of the atomic bomb blast at Trinity on July 16. “The explosion, the greatest to be caused by mankind in all history — up to the time the two atomic bombs were dropped on Japan — makes one of the most spectacular screen scenes ever filmed,” said Showman’s Trade Review.

On Sept. 15, the first films of what News of the Day called “atom-bombed Japan” finally reached newsreel screens. The footage showed the flattened landscape of Hiroshima, more obliterated even than Berlin and Tokyo, first from the aerial perspective of a B-29 and then from the ground, where a few Japanese civilians walk dazed through the ruins. The narration is blunt about the scale of the devastation and the number of causalities, but no images of the dead and wounded are screened. “Latest reports from the Japanese say 126,000 died as a result of the damage done by the single bomb that blasted the city,” reported Universal Newsreel announcer Ed Herlihy. “For many days after the actual bombing, thousands continued to die of burns and shock.”

Universal credited the footage to commercial newsreel and Army Air Force cameramen, but Japanese camera people were also on the scene in the immediate aftermath of the blasts documenting the backfire on their countrymen. They took some two hours and 40 minutes of motion picture footage, all of which was confiscated by U.S. Occupation forces. According to Edith Lindeman, film critic for the Richmond Times-Dispatch, writing in 1946, “the pictures were developed and readied for general consumption,” but government and military authorities soon had second thoughts. “Shots of dismembered bodies, piles of dead animals, and [of] a man whose body had been blown flat into a concrete road where it was imbedded by the blast” were so appalling that officials feared that American public might withdraw support for the testing of future atomic bombs.

A year later, however, on the first anniversary of the blasts, the U.S. government had third thoughts and released the footage to the newsreels. The newsreel editors were not unanimously receptive. Three of the outfits — News of the Day, Pathé and Fox Movietone — deemed the footage “too gruesome” to show to moviegoers settling in for an evening’s entertainment. Only Universal Newsreel and Paramount News opted to use the footage.

That same week, the military also released footage of the underwater atomic test near Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands, conducted on July 25, 1946, an awesome spectacle documented by 300 cameras (and later repurposed by Stanley Kubrick at the end of 1964’s Dr. Strangelove). The back-to-back coupling of the two segments — Bikini and Hiroshima, the shape of things to come followed by the human fallout — made for a grim all-atomic episode. Usually, the newsreels tried to soften even the harshest news at the top of the issue with a back-end clip of fashion or sports. Not this week.

The Universal Newsreel segment incorporated scant seconds of the Hiroshima victims, but Paramount lived up to its slogan as “the eyes and ears of the world.” The nine-minute issue (“Atom Bombs!” is the exclamatory title) devotes about half its running time to an unblinking look at the Japanese victims. (The news reel of Paramount News issue 99 is not currently available online; I viewed it with the help of multiple archivists, more on that at the end of this column.)

“One year has passed since the first atomic bomb changed the course of civilization,” reads the introductory title card. “This film report — of pictures just released from Hiroshima and the underwater Bikini test — highlights the new world crisis unleashed by the most terrible destructive force in history.” Offscreen narrator Maurice Joyce, the voice of Paramount News, takes over with an awed after-action report on the Bikini blast, noteworthy not just for the frame-filling, ballooning mushroom cloud (shown twice, from two different camera angles) but because the clip allots a full 30 seconds of tension to counting down the moment of detonation. Sailors aboard ships anchored near ground zero would have met “a terrible atomic death,” he says, a remark that serves as a transition to what “one year ago swept down on Hiroshima.”

The shift to “Hiroshima, August 6, 1945” is signaled by the clang of a Shinto temple gong on the soundtrack. First, we see a peaceful modern city before the blast and then a postapocalyptic vista of rubble. “This is how Hiroshima looked after the blast. Four and a half square miles almost completely burned out.”

T he final title card asks the question of the moment: “In light of these shocking films, the world faces a life-and-death question: CAN WE CONTROL ATOMIC POWER?”

Engaging in the kind of overt editorializing that the newsreels almost always avoided, Joyce demands an answer. Yet even with the stakes being nothing less than the future of mankind, politicians remain “deadlocked” and “the same old balance of power maneuvering continues.” At the close, the clip reprises the images from the Bikini explosion and Joyce signs off with a warning, “Unless there is complete agreement on the bomb, we may as well build our cities under the Earth and get ready for armageddon.”

The commentary was written by Paramount editor and future Time magazine film critic Weldon Kees, who felt he had done a good job of work that day. The newsreel “with the Bikini test and the Japanese films turned out amazingly well,” he wrote his parents back in Beatrice, Nebraska. “It is no doubt one of the best newsreels ever released.”

Senior management at Paramount News agreed. On Aug. 9, 1946, the outfit invited newspaper and trade press critics to a special screening of the issue at its New York headquarters. “The screen is the only real medium that adequately brings home the horrors of the bomb and it has done so indeed in this reel,” said Curtis Mitchell, Paramount’s director of advertising and publicity. “I hope it is shown in every theater in the world.”

That kind of saturation was unlikely. Most motion picture exhibitors were locked into contracts with one of the five newsreel companies. Though not a hard and fast rule, Fox-owned and-affiliated theaters tended to show Fox Movietone newsreels and so on. Thus, Paramount’s newsreel was screened in Paramount houses and by some independent exhibitors who had the freedom to mix and match. Paramount’s unique hard news scoop was also welcomed in all-newsreel houses, a circuit of venues in the major cities that played a one-hour program composed entirely of newsreels and short documentaries. “See Casualties and Damage by 1st A-Bomb!” urged the Tele News Theater in San Francisco. The Trans-Lux Theater in New York highlighted the Paramount clips in a similarly gruesome way. Still, even if you were an avid moviegoer in 1946, chances are less than even that you would have seen the Paramount News footage.

V iewers who did see the Paramount footage were stunned and sickened. “This clip becomes a real shocker because of the previously unseen shots of the devastation wrought on human beings by the atom bomb on Hiroshima,” wrote Jack D. Grant in The Hollywood Reporter in August 1946. (Tellingly, critics often resorted to the biblical verb “wrought” to describe the atomic visitation.) “Radioactive rays burned the pattern of one woman’s dress on her skin. Others were scarred and blinded in the most hideous manner. No punches are pulled in showing any part of the devastation. There are closing shots of school children, still disfigured a full year after Hiroshima.”

At Motion Picture Daily, critic Herb Loeb was especially distraught. “The scarred, burned, and maimed people caught by the Japanese camera at the height of their anguish forms a burning indictment against the use of the atomic bomb by any civilized country,” Loeb wrote. All agreed, in the words of Chester B. Bahn, editor of the Film Daily, that the Japanese “clips belong on every screen not only in the U.S. but throughout the world as a solemn warning to all peoples that it is indeed later than they think.”

That same month, with the exhilaration of V-J Day no longer at fever pitch, other media were also reckoning with the human cost of the bombs that ended World War II. On Aug. 9, the monthly screen magazine the March of Time released a timely issue titled “Atomic Power,” a science lesson that was more cautionary than celebratory. It opened with the mushroom cloud from Trinity and shots of what remained of Hiroshima, though no victims were in sight. In a testament to the unmatched cultural cachet conferred by the March of Time series, the scientists and bureaucrats instrumental in the Manhattan Project — including Albert Einstein and J. Robert Oppenheimer — obligingly reenacted their roles for the cameras, “We’ll know in 40 seconds,” says [the real] Oppenheimer, playacting the countdown on that fateful morning. Also in August 1946, The New Yorker published John Hersey’s issue-long essay “Hiroshima,” which evoked in prose what Paramount News projected on film.

After the surge of attention in August 1946, the footage lay dormant for more than two decades. Unlike the Holocaust footage, which was unspooled incessantly in documentaries on Nazism and in feature films such as Orson Welles’ The Stranger (1946), Sam Fuller’s Verboten! (1959) and Stanley Kramer’s Judgment at Nuremberg (1962), the newsreel footage from Hiroshima and Nagasaki was not resurrected by Hollywood initially. Cultural historian Greg Mitchell, author of The Beginning of the End: How Hollywood — and America — Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, argues that the absence was not happenstance. “The United States engaged in airtight suppression of all film shot in Hiroshima and Nagasaki after the bombings,” in a concerted campaign he calls “The Great Hiroshima Cover-Up.”

Photographs in the print press were not as easily shut down. On Sept. 29, 1952, Life magazine, under the headline “When Atom Bomb Stuck — Uncensored,” published a six-page spread of “scratched and dusty photographs” that, after being “suppressed by jittery U.S. military censors,” had recently “struck Japan with the impact of a delayed fuse bomb.” Letters poured in from shocked readers thanking the magazine for publishing “those terrible pictures.” With a readership at the time of around 25 million, the Life magazine spread probably attracted more eyes than the Paramount News issue.

The cinematic embargo was largely broken with Alain Resnais’ French-made, Hiroshima-set Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959, U.S. release May 1960). To wit: Hideo Sekigawa’s Hiroshima (1953, U.S. release May 1955), a harrowing docudrama about the aftermath of the bombing, received only limited art house distribution in the U.S.

At the top of Hiroshima Mon Amour, before the action veers off into more familiar nouvelle vague territory, the art house crowd was escorted through the displays in the Hiroshima Museum and saw (many doubtless for the first time) clips from the Japanese-shot newsreels. The contrast between the forefronted romance and the newsreel background, wrote Richard Gertner in Motion Picture Daily, “makes plain the horror of Hiroshima as no film on the subject has done before.”

In 1968, the existence of the long-buried footage came to the attention of Columbia University professor and pioneering media scholar Erik Barnouw. He contacted the Department of Defense and asked about the films. He was told the cache had recently been turned over to the National Archives, which furnished Barnouw with copies. Finally, U.S. officials “agreed with the intention to display to the general public the horrors of nuclear warfare,” reported Variety in 1970.

Working with Columbia University colleague Paul Ronder, Barnouw winnowed down the Japanese footage into a 16-minute short titled Hiroshima Nagasaki August, 1945. Hunched over a Steenbeck editing bed, Barnouw was stricken by what he saw, but confessed that it would be dishonest of him to say that in 1945 he greeted the news of the atomic bombings with anything other than relief. “It seemed to end the war very quickly,” he said.

H iroshima Nagasaki August, 1945 is low-key, bare-bones and devastating. “Eyes turned up to the bomb melted within nine seconds,” narrator Ronder intones, his voice flat and matter of fact. “One hundred thousand people were killed or doomed and 100,000 more injured.” On Feb. 19, 1970, Hiroshima Nagasaki August 1945 was first screened publicly in the United States at the Museum of Modern Art before what UPI called “a group of horrified spectators.” Seeking a wider audience, Barnouw and Ronder approached the transmission belt that had replaced the newsreels.

However, like three of the newsreel outfits in 1946, the three U.S. television networks refused to interrupt prime time programming with wartime horror. ABC and CBS declined to comment on the decision; NBC said the network was “waiting for a news peg.” The sudden skittishness — from network executives currently broadcasting the Vietnam war into American living rooms — did not go unremarked. “The most important documentary film of this, and perhaps any previous century, is being seen only by a select few,” complained the Boston Globe. “Surely [the networks] can find 16 minutes of prime time to show Americans what the first A-bombs, puny by [comparison to] today’s weapons, did to people and property 25 years ago!”

National Educational Television (NET), the ancestor of the Public Broadcasting System, seemed the next best forum for the film, but NET also claimed the footage contained “little that is new about it” and said it “doesn’t plan to show it.” However, under pressure from its outraged demographic, NET quickly reversed course. On Aug. 3, 1970, it telecast Hiroshima Nagasaki August, 1945 as part of an hourlong special. An ad in The New York Times described the footage as “never before shown on nationwide TV.”

Thereafter, Hiroshima Nagasaki August 1945 circulated widely. Within the year, Columbia had sold over 500 prints in 16mm, mostly to universities, libraries and peace groups. Sometimes writer-narrator Paul Ronder would attend a public screening. The response from audiences was always the same. “There is never any applause, always a sort of hush,” he said. “Then people stand up, find it hard to talk to one another, then sort of drift away.”

• • •

About this column: For all their absolute centrality in the telling of 20th century history onscreen, the newsreels have been a woefully neglected field in film studies. Ray Fielding’s The American Newsreel 1911-1967, published in 1972, remains the sole, go-to omnibus source. A documentarian or film scholar seeking an obscure newsreel issue must depend on the kindness of archivists — and hope that the issue, usually seen as disposable in its time, was preserved, somewhere, either by a commercial house or educational institution. Though Universal News donated its collection to the Library of Congress after it went belly up in 1967, and the internet has made it easier to find and screen newsreels, there is no central repository for the five major newsreels.

So, to track down a copy of the extraordinary Paramount News issue 99 (Aug. 9, 1946), I worked with a series of infinitely patient and gracious archivists. Josie Walters-Johnson at the Moving Image Research Center at the Library of Congress and Caitlin Hucik at the Moving Image and Sound Branch at the National Archives and Records Administration, helped locate the issue. The Sherman Grinberg Film Library, which owns the Paramount News collection, then provided a watermarked screener for me to eyeball. Luckily, the issue was preserved intact, as exhibited in 1946, on a ¾ inch Umatic videotape, that included the original soundtrack. NARA also has a copy available for screening on site at College Park, Maryland.

V iewers who did see the Paramount footage were stunned and sickened. “This clip becomes a real shocker because of the previously unseen shots of the devastation wrought on human beings by the atom bomb on Hiroshima,” wrote Jack D. Grant in The Hollywood Reporter in August 1946. (Tellingly, critics often resorted to the biblical verb “wrought” to describe the atomic visitation.) “Radioactive rays burned the pattern of one woman’s dress on her skin. Others were scarred and blinded in the most hideous manner. No punches are pulled in showing any part of the devastation. There are closing shots of school children, still disfigured a full year after Hiroshima.”

At Motion Picture Daily, critic Herb Loeb was especially distraught. “The scarred, burned, and maimed people caught by the Japanese camera at the height of their anguish forms a burning indictment against the use of the atomic bomb by any civilized country,” Loeb wrote. All agreed, in the words of Chester B. Bahn, editor of the Film Daily, that the Japanese “clips belong on every screen not only in the U.S. but throughout the world as a solemn warning to all peoples that it is indeed later than they think.”

T hat same month, with the exhilaration of V-J Day no longer at fever pitch, other media were also reckoning with the human cost of the bombs that ended World War II. On Aug. 9, the monthly screen magazine the March of Time released a timely issue titled “Atomic Power,” a science lesson that was more cautionary than celebratory. It opened with the mushroom cloud from Trinity and shots of what remained of Hiroshima, though no victims were in sight. In a testament to the unmatched cultural cachet conferred by the March of Time series, the scientists and bureaucrats instrumental in the Manhattan Project — including Albert Einstein and J. Robert Oppenheimer — obligingly reenacted their roles for the cameras, “We’ll know in 40 seconds,” says [the real] Oppenheimer, playacting the countdown on that fateful morning. Also in August 1946, The New Yorker published John Hersey’s issue-long essay “Hiroshima,” which evoked in prose what Paramount News projected on film.

V iewers who did see the Paramount footage were stunned and sickened. “This clip becomes a real shocker because of the previously unseen shots of the devastation wrought on human beings by the atom bomb on Hiroshima,” wrote Jack D. Grant in The Hollywood Reporter in August 1946. (Tellingly, critics often resorted to the biblical verb “wrought” to describe the atomic visitation.) “Radioactive rays burned the pattern of one woman’s dress on her skin. Others were scarred and blinded in the most hideous manner. No punches are pulled in showing any part of the devastation. There are closing shots of school children, still disfigured a full year after Hiroshima.”

At Motion Picture Daily, critic Herb Loeb was especially distraught. “The scarred, burned, and maimed people caught by the Japanese camera at the height of their anguish forms a burning indictment against the use of the atomic bomb by any civilized country,” Loeb wrote. All agreed, in the words of Chester B. Bahn, editor of the Film Daily, that the Japanese “clips belong on every screen not only in the U.S. but throughout the world as a solemn warning to all peoples that it is indeed later than they think.”

That same month, with the exhilaration of V-J Day no longer at fever pitch, other media were also reckoning with the human cost of the bombs that ended World War II. On Aug. 9, the monthly screen magazine the March of Time released a timely issue titled “Atomic Power,” a science lesson that was more cautionary than celebratory. It opened with the mushroom cloud from Trinity and shots of what remained of Hiroshima, though no victims were in sight. In a testament to the unmatched cultural cachet conferred by the March of Time series, the scientists and bureaucrats instrumental in the Manhattan Project — including Albert Einstein and J. Robert Oppenheimer — obligingly reenacted their roles for the cameras, “We’ll know in 40 seconds,” says [the real] Oppenheimer, playacting the countdown on that fateful morning. Also in August 1946, The New Yorker published John Hersey’s issue-long essay “Hiroshima,” which evoked in prose what Paramount News projected on film.

After the surge of attention in August 1946, the footage lay dormant for more than two decades. Unlike the Holocaust footage, which was unspooled incessantly in documentaries on Nazism and in feature films such as Orson Welles’ The Stranger (1946), Sam Fuller’s Verboten! (1959) and Stanley Kramer’s Judgment at Nuremberg (1962), the newsreel footage from Hiroshima and Nagasaki was not resurrected by Hollywood initially. Cultural historian Greg Mitchell, author of The Beginning of the End: How Hollywood — and America — Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, argues that the absence was not happenstance. “The United States engaged in airtight suppression of all film shot in Hiroshima and Nagasaki after the bombings,” in a concerted campaign he calls “The Great Hiroshima Cover-Up.”

Photographs in the print press were not as easily shut down. On Sept. 29, 1952, Life magazine, under the headline “When Atom Bomb Stuck — Uncensored,” published a six-page spread of “scratched and dusty photographs” that, after being “suppressed by jittery U.S. military censors,” had recently “struck Japan with the impact of a delayed fuse bomb.” Letters poured in from shocked readers thanking the magazine for publishing “those terrible pictures.” With a readership at the time of around 25 million, the Life magazine spread probably attracted more eyes than the Paramount News issue.

The cinematic embargo was largely broken with Alain Resnais’ French-made, Hiroshima-set Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959, U.S. release May 1960). To wit: Hideo Sekigawa’s Hiroshima (1953, U.S. release May 1955), a harrowing docudrama about the aftermath of the bombing, received only limited art house distribution in the U.S.

At the top of Hiroshima Mon Amour, before the action veers off into more familiar nouvelle vague territory, the art house crowd was escorted through the displays in the Hiroshima Museum and saw (many doubtless for the first time) clips from the Japanese-shot newsreels. The contrast between the forefronted romance and the newsreel background, wrote Richard Gertner in Motion Picture Daily, “makes plain the horror of Hiroshima as no film on the subject has done before.”

In 1968, the existence of the long-buried footage came to the attention of Columbia University professor and pioneering media scholar Erik Barnouw. He contacted the Department of Defense and asked about the films. He was told the cache had recently been turned over to the National Archives, which furnished Barnouw with copies. Finally, U.S. officials “agreed with the intention to display to the general public the horrors of nuclear warfare,” reported Variety in 1970.

Working with Columbia University colleague Paul Ronder, Barnouw winnowed down the Japanese footage into a 16-minute short titled Hiroshima Nagasaki August, 1945. Hunched over a Steenbeck editing bed, Barnouw was stricken by what he saw, but confessed that it would be dishonest of him to say that in 1945 he greeted the news of the atomic bombings with anything other than relief. “It seemed to end the war very quickly,” he said.

H iroshima Nagasaki August, 1945 is low-key, bare-bones and devastating. “Eyes turned up to the bomb melted within nine seconds,” narrator Ronder intones, his voice flat and matter of fact. “One hundred thousand people were killed or doomed and 100,000 more injured.” On Feb. 19, 1970, Hiroshima Nagasaki August 1945 was first screened publicly in the United States at the Museum of Modern Art before what UPI called “a group of horrified spectators.” Seeking a wider audience, Barnouw and Ronder approached the transmission belt that had replaced the newsreels.

However, like three of the newsreel outfits in 1946, the three U.S. television networks refused to interrupt prime time programming with wartime horror. ABC and CBS declined to comment on the decision; NBC said the network was “waiting for a news peg.” The sudden skittishness — from network executives currently broadcasting the Vietnam war into American living rooms — did not go unremarked. “The most important documentary film of this, and perhaps any previous century, is being seen only by a select few,” complained the Boston Globe. “Surely [the networks] can find 16 minutes of prime time to show Americans what the first A-bombs, puny by [comparison to] today’s weapons, did to people and property 25 years ago!”

National Educational Television (NET), the ancestor of the Public Broadcasting System, seemed the next best forum for the film, but NET also claimed the footage contained “little that is new about it” and said it “doesn’t plan to show it.” However, under pressure from its outraged demographic, NET quickly reversed course. On Aug. 3, 1970, it telecast Hiroshima Nagasaki August, 1945 as part of an hourlong special. An ad in The New York Times described the footage as “never before shown on nationwide TV.”

Thereafter, Hiroshima Nagasaki August 1945 circulated widely. Within the year, Columbia had sold over 500 prints in 16mm, mostly to universities, libraries and peace groups. Sometimes writer-narrator Paul Ronder would attend a public screening. The response from audiences was always the same. “There is never any applause, always a sort of hush,” he said. “Then people stand up, find it hard to talk to one another, then sort of drift away.”