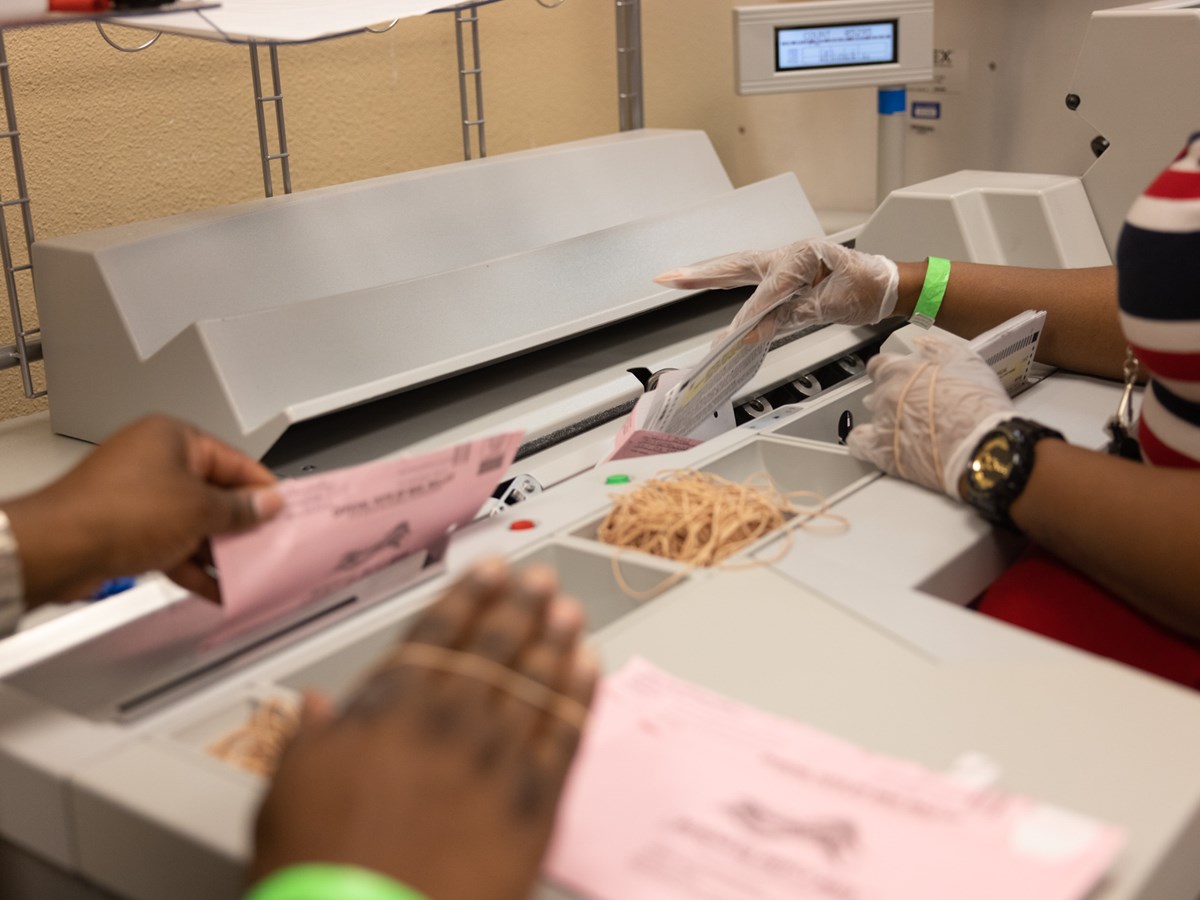

Norman Hamilton Jr. and Antoinette Heckard extract ballots from envelopes at the Sacramento County elections office on Tuesday, June 7, 2022.

Andrew Nixon / CapRadio

Organizers nationwide continue to push for larger voter participation by young people. But concerns of engagement for this November election still exist, especially in Sacramento where county outreach efforts aren’t as robust as in prior elections.

Though 18- to 24-year-olds make up only 7.6% of Sacramento County’s population, young people represent 12% of the county’s registered voters according to the Secretary of State’s office.

Still, since midterm elections historically elicit lower participation, experts say young voters may not head to the polls.

“Younger voters are just less enthusiastic about voting, which in many cases may lead them to be less enthusiastic about voting overall,” says Dean Bonner, the associate survey director at Public Policy Institute of California.

Sydnee Yu, a first time voter and college student in Los Angeles, will be mailing in her absentee ballot with excitement, but says the action of voting feels anticlimactic.

“I have the hope… that even though we might not necessarily be doing it in person, there will still kind of be a sense of a call to action within my community,” Yu said.

In California, every registered voter is sent a mail-in-ballot. It’s a novel concept prompted by the pandemic, and the data is not robust enough to predict voting patterns, Bonner said.

Eric McGhee, a senior fellow at the PPIC, says that “young voters are some of the least reliable voters,” which he says suggests that sustained engagement could be required for voter participation.

Two demographics of voting blocs — first-time and communities of color — benefit from strong voter outreach efforts. In California, Latinx, Asian Americans and African Americans were less likely to vote compared to their white peers, according to a 2020 survey results from the PPIC. And young Black voters were the least likely to vote, the survey showed.

McGhee says he noticed that in communities where diversity was more concentrated, there was a higher turnout of that demographic.

“Sacramento County is one of the more diverse counties in the state,” he said. “So you might expect that Black voters in Sacramento County might be more likely to turn out.”

Cliff Albright, co-founder and executive director of Black Votes Matter Fund, says targeted outreach and education on ballot initiatives increases young voter turnout. Albright’s organization focuses its efforts on the intersection of race and civic engagement.

“We’re in the situation of voter suppression, of white supremacy, of economic injustices and we’ve not gotten in this situation overnight,” Albright says. “So for us to come out of it, for us to build power, we’ve got to use a variety of strategies and tactics.

He added: “We’ve got to do that all throughout the year. We call it the 365 work.”

Advocates point to youth-led movements like the one that elected Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in 2018 as the youngest woman in Congress, or in 2020 when Stacey Abrams similarly garnered Georgia’s untapped voters of color to show up for the General Election.

Albright’s organization rallies first time voters at high schools, enables college students to push for change, and supports ballot initiatives that impact young students of color. They have partnered with the African Methodist Episcopal Church, which has locations in California, to increase voter participation. However, Black Votes Matter directed most of its energy to GOP heavy-states like Tennessee and Texas.

During June’s primary election, less than 39% of Sacramento County’s registered voters went to the polls — one of the lowest turnouts in the past few election seasons. Even in a Democrat-controlled state like California, the local races and measures can be a toss up. In Sacramento County, the local school board races have candidates with support on both ends of the political spectrum. And registered Republicans outweigh registered Democrats in Placer County.

Betty Williams, president of the NAACP of Greater Sacramento, said her team has been going to colleges and churches to get Black people registered, and even held a voter engagement event the weekend before the election at the Black Expo. They also dedicate voter education for unhoused people and ex-felons.

“Because we’re in Sacramento County, we have what a lot of states don’t have — they can register and vote on the same day. A lot of folks don’t know about that,” Williams said. “For the Black community, a lot of the times feel that historical moment of dropping off your ballot, and there is still that option.”

Williams says casting a ballot in person has resounding power in the Black community, and the loss of the cultural atmosphere on Election Day can play a role in civic engagement.

“Back in 2008, there were a number of African Americans running,” she says. “And as a result, we ended up having our first Black mayor, and we had four [Black] council members. And so now you look back from then to now, we literally have one Black council member.”

Williams says that because there hasn’t been a collective effort by organizations to increase Black voter engagement, it’s been difficult to get people to the polls.

Sacramento County’s voter outreach took a different approach this election cycle than in previous years because of staffing. While the county still did outreach like delivering in-language materials in zip codes with low registration, missing this year are the mock elections, which have proven to engage young voters.

Carrie Jackson, a former teacher in the Folsom Cordova Unified School District, pioneered the mock elections at Vista del Lago High School, which was facilitated by Sacramento County’s outreach department. Her students would create campaign posters for the mock elections, something that was not a requirement for the program.

“I think this is where students go, ‘Hey, wow, you know what? A career in politics is something that I’m really excited about,’”Jackson says. “And it was really cool because what sparked that was doing the mock elections last year when we did that at our school.”

Yu, the college student in Los Angeles, is one of the many young, first time voters of color to have shown an interest in civic engagement as a result of Sacramento County’s mock elections.

“It’s really led me to pivot into learning more about specific issues and trying to do advocacy,” says Yu.

Organizers say engaging the young voters requires consistent outreach and education, and deprioritizing those voters in a midterm election can have lasting implications.

Still, Williams says young voters will need to prioritize casting their ballots — especially in non-presidential elections.

“If you’re going to not show up to vote, whether it’s a primary election or a midterm election, then you are saying that it’s OK for [politicians] to do whatever they do to you. That’s what you’re saying,” cautions Williams.

She adds: “Know that they’re going to hide the diamonds in these elections, not in the major one.”

Correction: A previous version of this story misspelled Eric McGhee’s name.

Srishti Prabha is an education reporter and Report For America corps member in collaboration with CapRadio and The Sacramento Observer. Their focus is K-12 education in Sacramento’s Black communities.

Follow us for more stories like this

CapRadio provides a trusted source of news because of you. As a nonprofit organization, donations from people like you sustain the journalism that allows us to discover stories that are important to our audience. If you believe in what we do and support our mission, please donate today.