What the normalisation between two regional powers means and does not mean.

By Marwan Bishara

On March 10, Saudi Arabia and Iran announced an agreement to restore bilateral relations. That’s good news.

The deal was conceived out of need and out of desire: The Saudi-Iranian need to end a conflict that has proven costly and toxic to both nations and disastrous to the Middle East, and the Chinese desire to play matchmaker, to fill the strategic void left by the United States and Russia, and to demonstrate its credentials as a trustworthy global partner.

The fact that the agreement was signed after two years of difficult negotiations holds promise. But do not expect the long archrivals to turn archangels after normalising their diplomatic relations. There remains a great deal of distrust and too many points of friction to tackle and resolve.

With no love lost, the renewed Saudi-Iranian relationship may turn into a marriage of convenience driven by national interest and shaped by political and economic calculus. Or, it may become a marriage of inconvenience – one that is eroded by divergent ideological and regional agendas.

Riyadh and Tehran have agreed to reactivate the cooperation and security agreements signed in 1998 and 2001, respectively, but a return to the status quo ante of the 1990s is challenging if not improbable after a dozen years of hostility.

Indeed, their proxy conflicts have been utterly devastating with their sectarian overtones, undermining the two countries’ security, crippling their economies and tearing their societies apart. The more they interfered the more Yemenis, Syrians, Iraqis, Lebanese and Bahrainis suffered.

That’s why the way forward is not the way back for the two regional powers. In light of the new and complicated regional order – or rather disorder – they helped create, the two nations must chart a new and sustainable path forward that serves their and their neighbours’ national interests.

This begins with refraining from intervening in each other’s affairs, wasting fortunes on undermining other Middle Eastern societies, and in the process, engaging in a costly arms race to the bottom.

Like other peoples, Iranians and Saudis would want their leaders to focus their attention on domestic affairs, not foreign bravados, pursuing democratic harmony at home instead of spreading anarchy abroad.

A new way forward is an opportunity to lower tensions, mitigate the damages, and compensate neighbours for the harm done to them. It is indeed morally incumbent upon the two oil-rich nations to help Syrians, Yemenis and other victims of proxy conflicts rebuild their shattered lives. China and the West should also help.

Beyond that, I believe it is in everybody’s best interest if the protagonists try a hands-off approach to regional affairs, especially as their regional overreach allowed foreign powers to exploit and aggravate their conflict.

Indeed, Riyadh and Tehran must now take a common, firm stand on foreign interference, especially Western support for Israel’s colonialism and apartheid – predictably the only country to openly oppose the new Gulf détente, which it is, no doubt, determined to sabotage.

They must also reject all attempts by global powers to intervene directly or through proxies in the Middle East. That includes China.

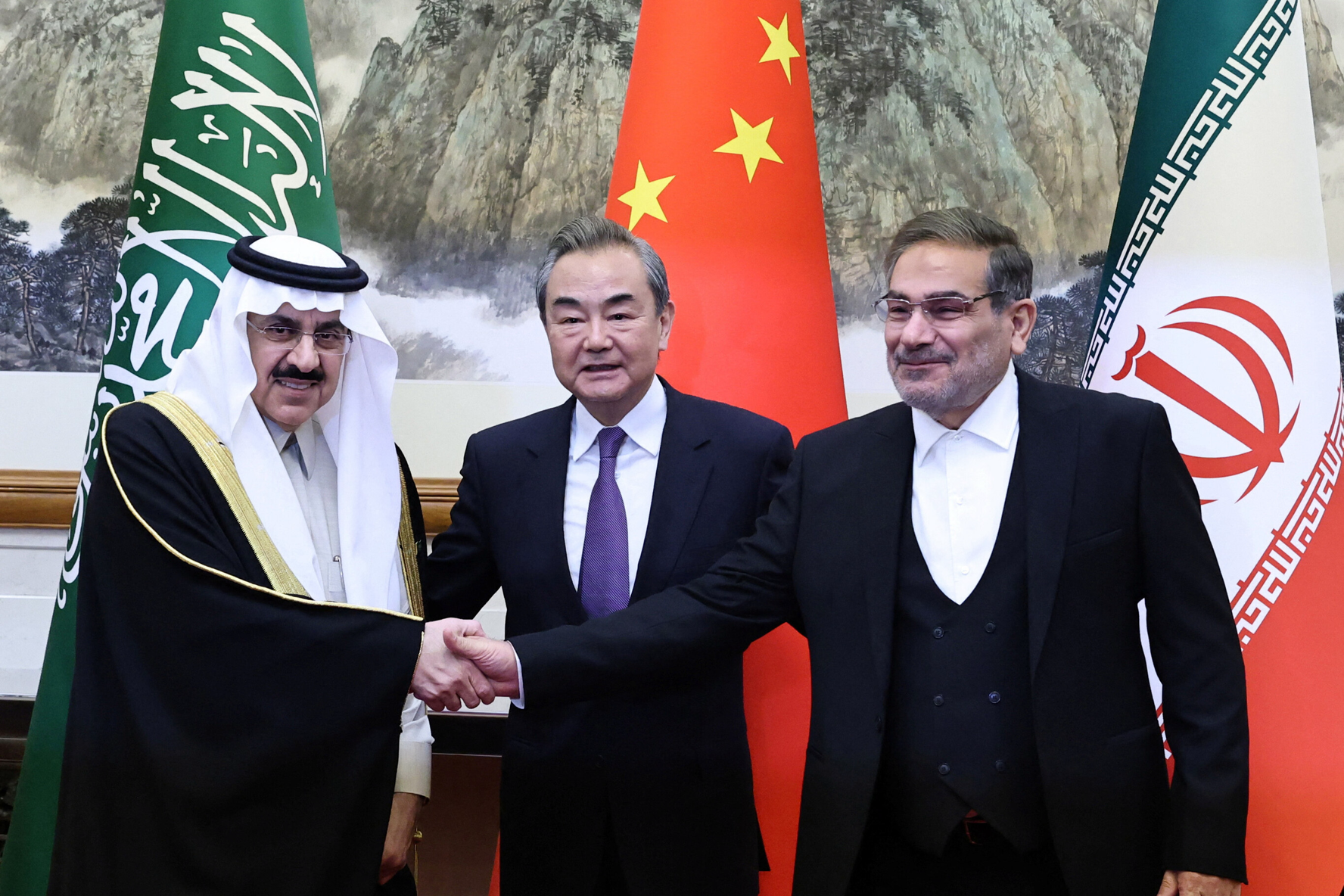

Beijing, which mediated between Riyadh and Tehran and hosted the final celebratory handshake, has emerged as the biggest winner of the new deal. It will gain greater credibility and prestige as a responsible global player, having helped resolve a complicated conflict in a tough region considered part of the US area of influence.

Moreover, as the sponsor, China will probably want to stay involved in order to see through the reconciliation and normalisation process, which gives it greater access to the oil-rich region it needs to fuel its economy and military in the long run. In other words, unlike other regional mediations that came at a cost to their sponsors, this could prove profitable to China, and at the expense of its global rival, the US.

The Biden administration has welcomed the de-escalation in the Gulf, which it says could also help put an end to the war in Yemen, but it is unable to hide its anger and disappointment. This is especially so since Beijing succeeded in championing a diplomatic breakthrough in the Middle East after Washington tried to block its mediation between Russia and Ukraine.

The US’s grinning mouth fails to hide its teeth-grinding, as China undermines US plans to expand the so-called Abraham Accords to include Saudi Arabia, or to impose a new nuclear deal on Iran through sanctions and regional pressure. Although it is too early to tell, the Chinese-sponsored agreement may well scuttle the American-Israeli scheme of polarising the region in favour of a pro-Israel and anti-Iran bloc.

But then again, Saudi Arabia is not about to turn its back on the US or switch alliances. It is far too dependent on Washington in military and economic affairs. But like other regional actors, large and small, Riyadh is also going hybrid, merely adding one more relationship to its diplomatic mix, aimed at securing its own interests first and foremost.

So will Iran, which has already developed relations with Russia and China. It may well add the US to the mix, if or when the latter agrees to lift the sanctions and strike a fair nuclear deal.

In other words, the Saudi-Iran deal is an indication of a changing region and shifting geopolitics.

Welcome to the new Middle East, where states are acting more independently of global powers, shaping and balancing relationships and alliances, instead of being shaped by them.