The systematic deletion of Latinx people by government databases, media organizations, and Hollywood has enabled killer cops, inhumane immigration policies, and more.

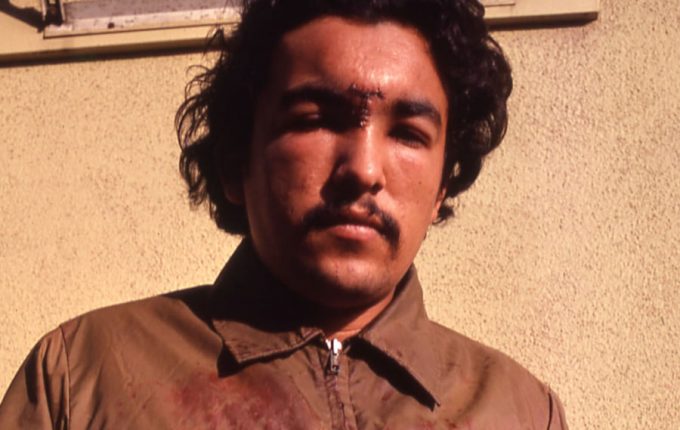

On the night of March 23, 1979, Roberto Cintli Rodriguez lost his ability to dream. Rodriguez, a journalist, was in East Los Angeles reporting for an article in Lowridermagazine about police violence when four baton-wielding LA County sheriffs beat the living dreams out of him.

As he recalls the incident, I remember reading about the 538 mostly young, brown kids arrested that weekend. Their crime? Cruising on Whittier Boulevard—the de facto center of the lowriding world. I have my own stories of official violence going back to the police beatings of local Latino cruisers under San Francisco Mayor Dianne Feinstein in the 1980s. I identified with Rodriguez’s story—a story the city’s main news outlet, the Los Angeles Times, ignored. But I had no idea about the astonishing effects the assault would have on him decades later.

“For years, I literally couldn’t remember my dreams or my nightmares,” he tells me during our conversation last week. “Those parts of me were erased.”

Last May, Roberto, an associate professor emeritus in the Mexican American Studies Department at the University of Arizona, released the latest iteration of one of his most important dreams: the Raza Database Project (RDP), a project aiming to document the nightmarish, violent effects of Latinx erasure. He and a team of volunteer researchers, journalists, and family members of Latinos killed by police produced a definitive report documenting an undercount of over 2,600 Latinos who have died at the hands of local police officers since 2014, a number that’s twice as large as what was previously reported.

There, in the cold anonymity of the statistics, he saw the mark of his old foe: erasure.

“One day,” he says, “I was looking at the ‘Unknowns’—people not identified in any racial or ethnic category—and saw all these names I recognized: Lopez, Martinez, Gonzalez, Ramirez. I asked myself, ‘Why are these people in this category?’ Because the federal government doesn’t keep a comprehensive, standardized count of who’s killed.”

His project and story bring to mind the forgotten names and images encountered during recent drives to numerous California cities and towns: Sean Monterrosa, an unarmed man shot and killed in Vallejo on June 2, 2020; James De La Rosa, a 22-year-old oil field worker shot dead by police officers in Bakersfield (where police officers have killed more people per capita than anywhere else in the United States); Andrés Guardado, an 18-year-old Salvadoran man shot in the back and killed by the same Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department that beat Roberto. While locals know their names, these and thousands of others remain faceless and story-less in the annals of US police violence.

“California,” Roberto adds “is literally a killing field everywhere, but nobody outside our community knows it.”

Roberto’s journey into the heart of darkness of police killings points to an even larger issue: how the systematic deletion of Latinx people by government databases, the media, philanthropy, Hollywood, and other institutions enables not just police violence but a whole host of other ills. From devastating immigration policies and employment discrimination, to reduced government funding and the colonization of Puerto Rico, these and other afflictions all have an element of removing Latinx people from their own stories.

This institutional erasure refers to the ways institutions and society at large suppress or completely silence a group in archives and narratives, as well as in discourse that subtly dehumanizes and sets up Latinx peoples for various forms of oppression.

Roberto’s talk of California as a “killing field” is familiar to me. I recall the silences that preceded the mass murder of hundreds of thousands of Central American peasants ignored before and during and after the war of the 1980s.