The U.S. has reached peak therapy. Counseling has become fodder for hit books, podcasts, and movies. Professional athletes, celebrities, and politiciansroutinely go public with their mental health struggles. And everyone is talking—correctly or not—in the language of therapy, peppering conversations with references to gaslighting, toxic people, and boundaries.

All this mainstream awareness is reflected in the data too: by the latest federal estimates, about one in eight U.S. adults now takes an antidepressant and one in five has recently received some kind of mental-health care, an increase of almost 15 million people in treatment since 2002. Even in the recent past—from 2019 to 2022—use of mental-health services jumped by almost 40% among millions of U.S. adults with commercial insurance, according to a recent study in JAMA Health Forum.

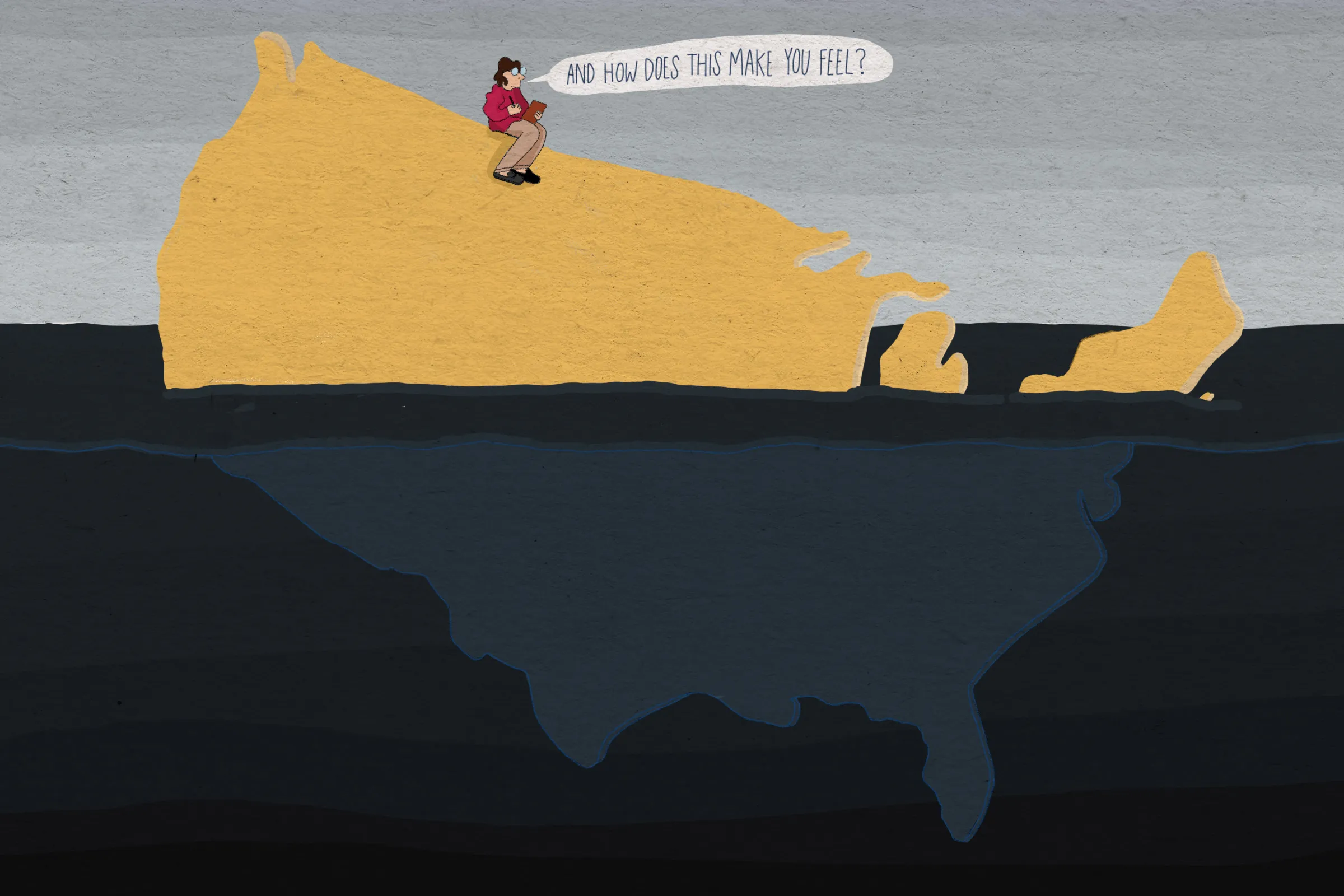

But something isn’t adding up. Even as more people flock to therapy, U.S. mental health is getting worse by multiple metrics. Suicide rates have risen by about 30% since 2000. Almost a third of U.S. adults now report symptoms of either depression or anxiety, roughly three times as many as in 2019, and about one in 25 adults has a serious mental illness like bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. As of late 2022, just 31% of U.S. adults considered their mental health “excellent,”down from 43% two decades earlier.

Trends are going in the wrong direction, even as more people seek care. “That’s not true for cancer [survival], it’s not true for heart disease [survival], it’s not true for diabetes [diagnosis], or almost any other area of medicine,” says Dr. Thomas Insel, the psychiatrist who ran the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) from 2002 to 2015 and author of Healing: Our Path from Mental Illness to Mental Health. “How do you explain that disconnect?”

Dr. Robert Trestman, chair of the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Council on Healthcare Systems and Financing, says there are multiple factors at play, some positive and some negative. On the positive side, more people are comfortable seeking care as mental health goes mainstream and becomes less-stigmatized, increasing the total number of people getting diagnosed with and treated for mental-health issues.

Less positively, Trestman says, more people seem to be struggling in the wake of societal disruptions like the pandemic and the Great Recession, driving up demand on an already-taxed system such that some people can’t get the support they want or need.

Some experts, however, believe the issue goes deeper than inadequate access, down to the very foundations of modern psychiatry. As they see it, the issue isn’t only that demand is outpacing supply; it’s that the supply was never very good to begin with, leaning on therapies and medications that only skim the surface of a vast ocean of need.

What’s really in a diagnosis

In most medical specialties, doctors use objective data to make their diagnoses and treatment plans. If your blood pressure is high, you’ll get a hypertension drug; if cancerous cells turn up in your biopsy, you might start chemotherapy.

Psychiatry doesn’t have such cut-and-dry metrics, though not for lack of trying. Under Insel, numerous NIMH research projects aimed to find genetic or biological underpinnings of mental illness, without much payoff. Some conditions, like schizophrenia, have clearer links to genes than others. But by and large, Insel says, “we don’t have biomarkers. We don’t have a lot of things that you would have in other parts of medicine.”

What psychiatry has is its Bible, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). The DSM sets diagnostic criteria for mental-health conditions largely based on symptoms: what they look like, how long they last, how disruptive they are. Relative to other medical fields, this is a fairly subjective approach. It’s essentially up to each clinician to decide, based on what they observe and their patient tells them, whether symptoms have crossed the line from normal to disorder—and this process is increasingly occurring during brief appointments on teletherapy apps, where things can easily slip through the cracks.

Dr. Paul Minot, whose nearly four decades as a psychiatrist do not stop him from vocally critiquing the field, feels his industry is too quick to gloss over the “ambiguity” of mental health, presenting diagnoses as certain when in fact there’s gray area. Indeed, research suggests both misdiagnosis and overdiagnosis are common in psychiatry. One 2019 study even concluded that the criteria underlying psychiatric diagnoses are “scientifically meaningless” due to their inconsistent metrics, overlapping symptoms, and limited scope. That’s a sobering conclusion, because diagnosis largely determines treatment.

“If I’m giving you an antibiotic but you have a viral infection, it’s not going to do anything,” Trestman says. Similarly, an antidepressant may not work well for someone who actually has bipolar disorder, which can be mistaken for depression. This imperfect diagnostic system may help explain why, even though antidepressants are one of the most-prescribed drug classes in the U.S., they don’t always yield great results for the people who take them.

Joseph Mancuso, a 35-year-old DJ, music producer, and content creator in Texas who uses the stage name Joman, has been in and out of the mental-health care system since he was a teenager. Over the years, he’s received a range of diagnoses, including depression and bipolar disorder, that he says never felt quite accurate to him. (More recently, he received a diagnosis that felt right: complex post-traumatic stress disorder.) These diagnoses led to numerous prescriptions, some of which helped and many of which didn’t. “I felt at times that I was just a dartboard and they were just throwing darts and seeing what would stick,” he says.

Some treatments don’t seem to stick regardless of whether a patient was properly diagnosed. In a 2019 review article, researchers re-analyzed data used to assess the efficacy of supposedly research-backed mental-health treatments. Some methods—like exposure therapy, through which people with phobias are systematically exposed to their triggers until they’re desensitized to them—came out looking good. But a full half of the therapies did not have credible evidence to back them, the authors found.

“It’s not the case that, holy shit, therapy just doesn’t work at all,” says co-author Alex Williams, who directs the psychology program at the University of Kansas. But Williams says the results inspired him to make some changes in his practice, leaning more heavily on therapeutic styles with the best data behind them.

Over-medicated…and over-therapized?

Even styles of therapy with solid evidence behind them can vary in efficacy depending on the clinician at the reins. One of the best predictors of success in therapy, research has shown, is the relationship between patient and provider—which may explain why it can feel like a crapshoot, with some people leaving their sessions feeling enlightened and empowered and others feeling the same as when they walked in.

The latter scenario was the case for “Shorty,” a 31-year-old from North Carolina who asked to be identified by his nickname to preserve his privacy. Shorty became disillusioned with therapy after trying it while struggling with substance abuse in college. “We just talked,” he says, “but we [weren’t] really solving anything. I was just paying this dude money.”

Some people may indeed benefit from therapy, Shorty says. But it annoys him that the practice is sometimes seen as an automatic fix for life’s problems when both anecdotal evidence and scientific data suggest it doesn’t work for everyone. The APA says about 75% of people who try psychotherapy see some benefit from it—but not everyone does, and a small portion may even experience negative effects, studies suggest. Those who improve may need 20 sessionsbefore they have a breakthrough.

Given the significant investment of time, money, and energy that may be required for therapy to succeed, it’s perhaps unsurprising that medication, which is by contrast a quicker fix, is so popular. As of 2020, about 16% of U.S. adults had taken some kind of psychiatric drug in the past year. Within that class, antidepressants are the most commonly used.

There certainly are people who report that their symptoms improve or disappear after taking an antidepressant, and research suggests they are particularly effective for people with severe depression. People with anxiety and other conditions may also benefit from their use, according to the National Library of Medicine. But the data on antidepressants aren’t as solid as one might expect for one of the most widely used drug classes on the market.

In the early 2000s, the NIMH ran a large, multi-stage trial meant to compare different antidepressants head-to-head, in hopes of determining whether some worked better than others across the board or in specific groups of patients. Instead, Insel says, “what we came out with was the evidence that, actually, none of them are very good. It was really striking how poorly all of the antidepressants performed across the entire population.” Most people had to try multiple drugs, or take multiple at once, to go into remission, and about 30% of people in the trial never saw complete relief. Lots of people also dropped out before the study ended.

In the years since, studies have reached lukewarm findings about antidepressants. A 2018 meta-analysis of data from 522 trials found that all of the 21 analyzed drugs worked better than placebos—but their benefits were “mostly modest.” A 2019 review went further, concluding that antidepressants’ effects are “minimal and possibly without any importance to the average patient with major depressive disorder.”

Dr. Joanna Moncrieff—a founding member of the Critical Psychiatry Network, a group for psychiatrists who are skeptical of the mental-health establishment—believes that’s because some antidepressants don’t work the way they’re advertised. For decades, researchers theorized that depression stems from a shortage of mood-regulating neurotransmitters, particularly serotonin, in the brain. Blockbuster antidepressants like Prozac, which hit the U.S. market in the 1980s, are meant to boost those serotonin levels.

But Moncrieff’s research, as well as other scientists’ work, suggests that depression isn’t caused by low serotonin levels, at least not entirely. And if serotonin isn’t the main problem, Moncrieff says, taking these drugs is “not correcting a chemical imbalance. It is creating a chemical imbalance.”

So why do some people feel better after taking antidepressants? They clearly have some effect on the brain, potentially improving mood, but Moncrieff isn’t convinced they’re really treating the root cause of depression. To do that, she believes, clinicians need to help people solve problems in their lives, rather than simply prescribing a pill.

“Lots of people would disagree with that,” Moncrieff admits. But studies, including the 2019 research review on psychiatric treatments, do show that “problem-solving therapy,” a modality that teaches people how to manage stressors, can work.

The antidepressant drug Prozac is pictured in a Cambridge, Ma., pharmacy on March 9, 2006.

JB Reed/Bloomberg—Getty Images

That’s the approach taken by Minot, who believes psychiatry is too quick to label feelings like sadness and worry as symptoms rather than helping people understand where they come from, what they mean, and how to overcome and even grow from them. In some cases, he says, feeling bad can motivate people to change problematic habits, choices, or relationships.

Not everyone is convinced by this argument. Sadness may be part of life, but Insel says that’s an entirely different beast than depression, which can manifest more like feeling “dead” and may have no clear link to what’s going on in someone’s life. “People who think that’s just on the continuum of the human experience…have never met anybody who’s truly depressed,” he says.

Minot agrees that severe depression, as well as serious mental illnesses like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, may require pharmaceutical treatment. Overall, though, he feels psychiatry leans on medications so it doesn’t have to do the more difficult work of helping people understand and fix life circumstances, habits, and behaviors that contribute to their problems.“If you can sell people Band-Aids,” Minot asks, “why bother curing them?”

Dr. Edmund Higgins, an affiliate associate professor of psychiatry at the Medical University of South Carolina, has grappled with this tension in his own work with incarcerated people—many of whom, he says, would benefit from therapy. But without the time and resources to do that long-term work, he’s mostly limited to writing prescriptions. “You can put them on medicines and they’ll have some improvement,” in some cases more than others, Higgins says. “But guess what? They’re still anxious and depressed.”

There are a couple reasons for that, Higgins says. One is that changing the brain can be difficult, and currently available treatments aren’t always up to the task. Another is that “so much of our mood and [mental health] is situational.”

A medication might help with symptoms, but it can’t overcome the basic facts of someone’s life, whether they’re incarcerated, going through a divorce, being bullied at school, dealing with discrimination, or struggling with loneliness. Nor can a pill change the fact that we live in a bitterly divided country where gun violence is common, the effects of climate change are obvious, more than 10% of the population lives in poverty, bigotry persists, COVID-19 is still spreading, and the legal system is rolling back rights.

“A lot of people are suffering from material conditions and [are] having a reasonable, rational human response to suffering,” says Mancuso, the musician from Texas. But in his experience, the psychiatric system doesn’t always acknowledge the range of factors that can influence mental health—from personal trauma all the way up to the geopolitical climate—and instead seems more focused on getting people diagnosed, medicated, and out the door.

Mancuso points to a sentiment expressed by the philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti: “It is no measure of health to be well-adjusted to a profoundly sick society.”

Beyond the couch

Improving mental health at scale, Insel agrees, requires the system to look beyond the therapist’s couch. (Insel co-founded a startup focused on community-based behavioral care.) Seemingly non-medical solutions—like improving access to affordable housing, education, and job training; building out community spaces and peer support programs; and increasing the availability of fresh food and green space—can have profound effects on well-being, as can simple tools like mindfulness and movement.

“That’s not the way we roll in health care,” Insel says, but that’s incrementally changing. California, for example, has made efforts to broaden what qualifies as health care, and the federal government is funding an expansion of the country’s network of Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics, which provide a range of behavioral and physical health services.

Nonetheless, policy solutions are complex, slow-moving, and not guaranteed to take effect—particularly in a bitterly divided political system. So in the meantime, expanding access to mental-health care is important, the APA’s Trestman maintains. A system that is short an estimated 8,000 providers is never going to do its job perfectly, particularly when the existing network is concentrated in certain geographic areas, does not reflect the diversity of the U.S. population, and is financially out of reach for many people.

To make the biggest dent in rates of mental illness, Insel says the system needs to focus on adding resources in the right places. Teletherapy has grown enormously since the pandemic, which is important but has limitations. Many teletherapy apps meet demand by expecting clinicians to take on a huge quantity of short appointments, TIME’s previous reporting has found, which makes it difficult for providers to diagnose accurately, establish a rapport with patients, and provide holistic care.

Plus, it’s not clear that online services adequately serve people “in the deep end of the pool,” Insel says. Patients with severe psychiatric diagnoses often need specialized care that can’t be effectively offered through a mass-market app, and may not have the resources to access these services anyway. Brick-and-mortar, community-based care still plays an important role for people with serious mental illness, Insel says.

Focusing on quality, not just quantity, of care is also important, Trestman says. To the extent that people receiving mental health care are measured, these metrics usually focus on process—how long they’ve been seen, whether they schedule follow-up appointments—rather than whether their condition is improving, Trestman says. Research suggests fewer than 20% of mental-health clinicians measure changes in symptoms over time.

“What really matters is, is someone getting better? Are they able to return to work? Are they able to care for their family? Are they able to start planning for their future?” Trestman says. “Those are the key issues that we’re talking about, and those are just not measured in any consistent way.”

In his own practice, Trestman asks patients to define their priorities and what successful treatment means to them. These data may not be as objective as a blood test, but they build in some of the accountability Trestman feels is often lacking.

Patients like Mancuso are hungry for an approach that goes even further—one that recognizes the influence of the world beyond their therapist’s door and focuses not on medication, but on real-world improvement and understanding. That kind of care isn’t always the default of a for-profit system struggling to meet demand. But Mancuso believes it’s what’s necessary to see improvements in mental health at both a national and personal level.

“I had a rough upbringing. I had a lot of people take advantage of me. I was bullied really badly in school,” Mancuso says. “I needed more than pills. I needed guidance.”