When Suryakant “Suri” Nathwani returned from the hospital, the reserved 81-year-old grabbed his son’s hand and pleaded to be allowed to die at home. “He said, ‘Please promise me one thing: If I’m going to go, I’m going to go here. Do not take me back there,'” his son Raj Nathwani said.

Death was not an outcome Raj, 55, was willing to accept — but he knew his father’s chances of surviving coronavirus were not in his favor.

Raj had been tracking the virus since January, watching countless news reports: about the toll it had taken on multigenerational households; about medics in Italy’s overstretched health system being too swamped to make home visits; about elderly people in China with pre-existing conditions — including the one his father has — having a higher chance of dying.

“I’m not a betting man, but if I was… [I would] definitely put my money on him not making it,” Suri’s family doctor, general practitioner Dr. Bharat Thacker, told CNN.

The coronavirus pandemic has killed more than 219,000 people worldwide, according to figures from Johns Hopkins University in the US.

But official death tolls are largely made up of patients who died in intensive care wards or other hospital departments. The number of people dying in the community — many in their own homes or care homes — are often under-reported.

As he helped Suri up to bed after his arrival home from Watford General Hospital, on the outskirts of London, Raj worried whether the desperate series of events that had seen the virus spread across the globe would turn his father into another statistic.

Raj, a director of insight at an advertising firm, remained outwardly positive: “You’re not going to die. We’re going to look after you here,” he told his father. What he did not know was just how successful he would be.

The descent

Raj, who had himself recovered from a heart attack last November, was prepared for the pandemic weeks before the UK lockdown began on March 23. He had been in self-isolation alongside his 80-year-old mother and his father, who has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), since March 11, because the entire household was considered to be at high risk from coronavirus.

But his father’s condition began to deteriorate on March 25. Suri’s daily 10-minute walk outside the family home turned into a 45-minute stagger. His lung condition was flaring up. He looked fatigued, listless, and — although he did not display the high temperature or persistent cough, which the NHS considered the main symptoms of the virus — Raj suspected his father had Covid-19.

Unbeknownst to the family, Suri’s lungs were filling with liquid — a fact that was spotted by paramedics called to the family’s home the following day, when the octogenarian had trouble breathing.

He was taken to hospital, but doctors called Raj shortly afterward. He says they told him they were 95% sure Suri had the virus, but that they wanted to discharge him and send him home.

Raj says a senior consultant told him that if Suri’s condition worsened they would not ventilate him “because he felt his lungs, with … COPD, would not be able to handle it.”

CNN has reached out to Watford General Hospital for comment on Suri’s case, but has not received a response. CNN has seen Suri’s discharge sheet, which includes a “do not resuscitate” (DNR) order that was completed upon his admission.

Ventilation can be life-saving, but even in ordinary times, health practitioners warn that being admitted into intensive care gives no guarantee of recovery for older patients.

Raj said he was left with two choices: “Do I keep him there and risk never seeing him again, or do I bring him home and spend all my energy making it comfortable for him?” He chose the latter, even at the risk of spreading the infection through the entire household.

Before Suri returned to his Watford home — in a local taxi, as there was no ambulance available to move him — Raj spent the afternoon cleaning the house, isolating his mother on the ground floor, and turning his parents’ first floor bedroom into a makeshift hospital ward.

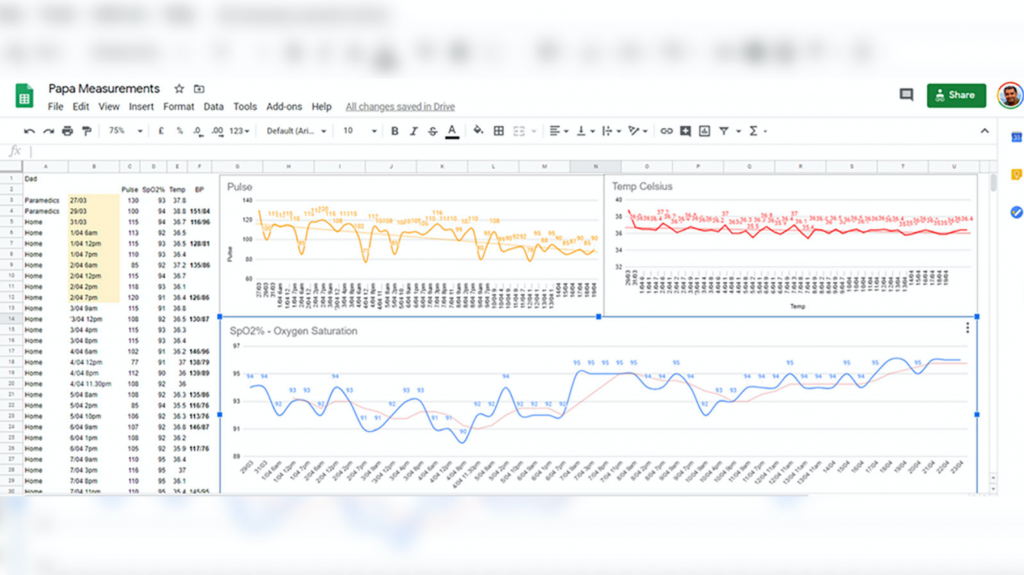

With little medical knowledge, or advice from the hospital on how to administer palliative care, Raj resorted to doing what he did best: collecting and analyzing data. He created a Google spreadsheet to help track his father’s temperature, blood pressure and oxygen saturation readings — vitals that could be measured with a store-bought thermometer, blood pressure monitor and pulse oximeter.

To limit the amount of time Raj spent in the room, an iPad was set up with a baby monitor app. This enabled the rest of his tight-knit family to help out, giving Raj’s brother, Manish, who lives in the US, and his sons, who live nearby with their mother, the opportunity to check in on Suri, helping to ease his lonely isolation. It also meant they could take turns monitoring him when Raj needed to rest.

The strategist also turned to a family friend, a general practice doctor, for advice. The GP advised on Suri’s hydration, and kept track of his vital signs on the Google spreadsheet.

Raj says that perhaps the key factor when it came to treating his father was the fact that their home was already equipped with a continuous positive airway pressure, or CPAP machine, for Suri’s sleep apnea.

“When Dad’s breathing got worse, I was advised to use the machine,” he said, explaining that when his father’s condition was at its most serious, the device — which helps patients breathe more easily — was being used for up to 16 hours a day on the doctor’s advice.

Three days after he was discharged, Suri was delirious, struggling to eat, and told Raj he thought he was close to the end. Raj believes this was because his brain was being starved of oxygen.

The recovery

The following day, Dr. Thacker called with the news that Suri’s coronavirus test had come back positive. At that point, many British GPs like Thacker were struggling to get hold of full personal protective equipment (PPE), such as a full-length gown and gloves.

Without PPE, it was unsafe for Thacker to make a home visit to coronavirus patients like Suri. “If I went there and I got it, then not only are my family at risk, but so are my patients if I returned to the surgery,” he told CNN.

Instead he checked the Google spreadsheet, and recommended an antibiotic for a secondary lung infection Suri had developed. The GP also advised that Suri should be helped to lie on his stomach for a number of hours a day — a practice known as prone positioning. Doctors have found that placing the sickest coronavirus patients on their stomachs can help increase the amount of oxygen getting into their lungs.

Knowing the seriousness of Suri’s condition, Thacker said a DNR notice was issued for the family’s address so that any paramedics who were sent there knew not to resuscitate the man, since “the outcome is going to be rather poor.”

Thankfully, it was not needed. Under his son’s watchful eye, Suri gradually began to recover. Raj says he knew his father was on the road to recovery when he became strong enough to nag him. “He began whingeing and said his tea was badly made. He then asked for some pizza and chips,” Raj said.

Eventually, Suri was given the all-clear, and by last week, he was walking the length of his garden with the help of a zimmer frame, or walker — inspired by Capt. Tom Moore, the 100-year-old British war veteran who has raised millions of pounds for the UK’s National Health Service by walking 100 laps of his garden.

“We truly had an action and ‘go-to’ team on tap that I trusted,” Raj said, adding he did not have to rely on “Dr. Google,” because he had real doctors nearby to help.

He said he appreciates that he and his father were in a more privileged position than many in the UK, where the virus is disproportionately affecting black and ethnic minority communities.

Thacker, who has had a number of patients die of Covid-19, says he cannot put his finger on exactly what worked for Suri.

“Whether it was the family caring for him, or the available bio-data that made the difference — we don’t know,” he said, adding: “Perhaps it was just luck and not quite his time to go.”

In the darkest moments, sometimes a plan of action and a little luck are the only things people have.