“Bad Reviews” pens a love letter to harsh critique by framing it as an endangered art—and giving artists space to laugh at their own misfires.

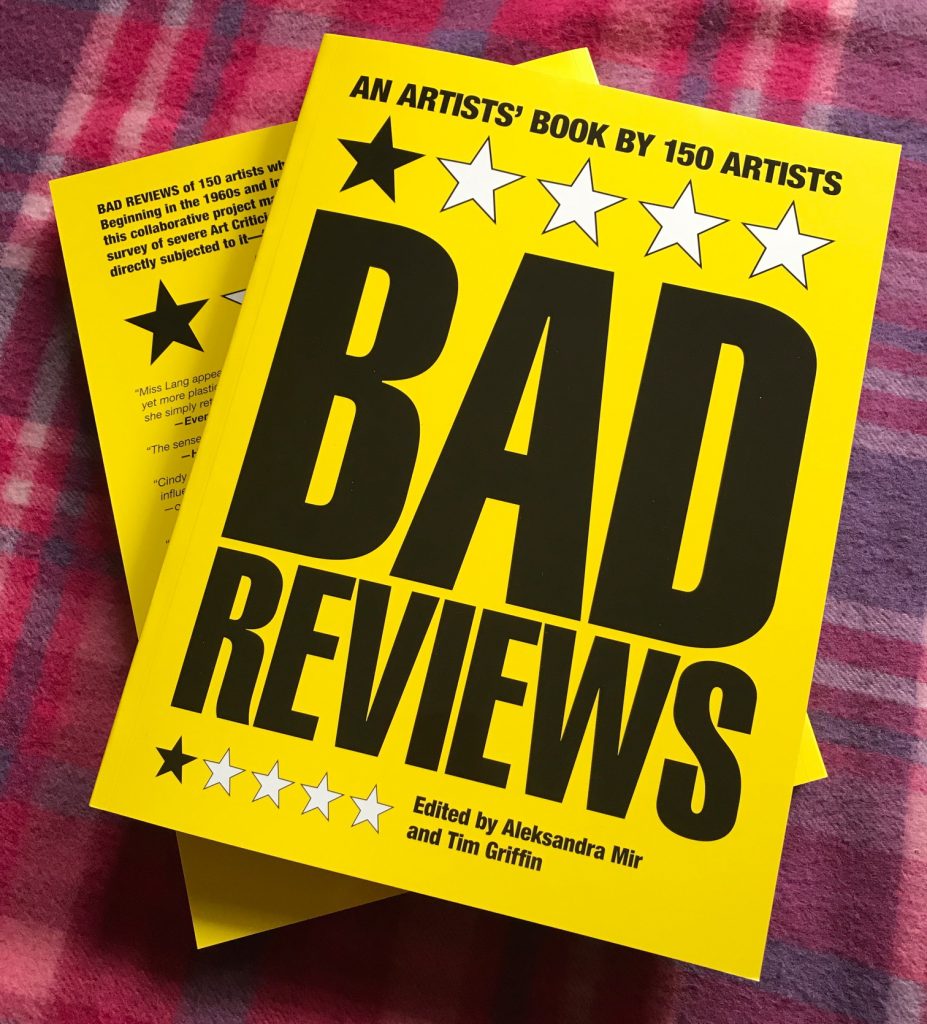

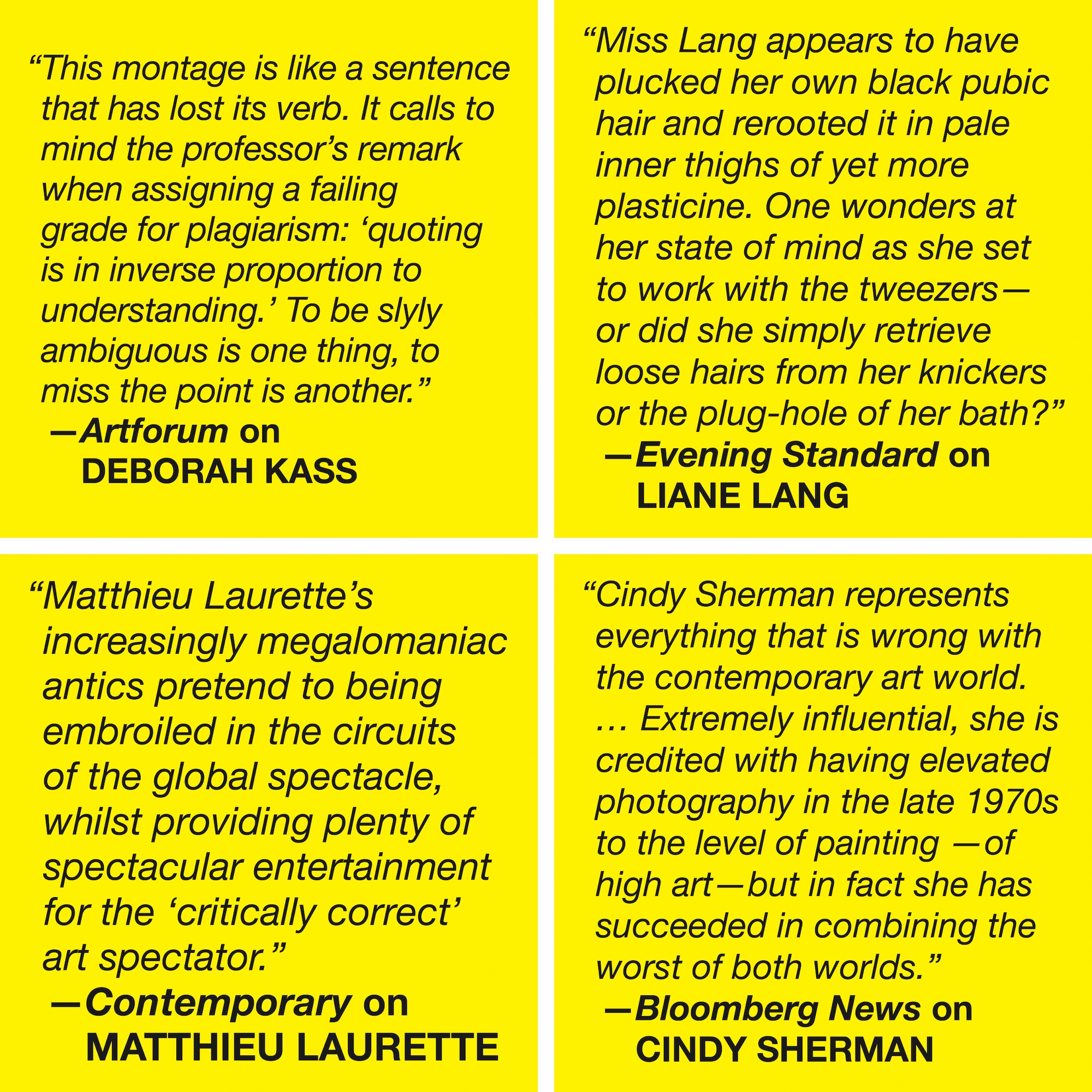

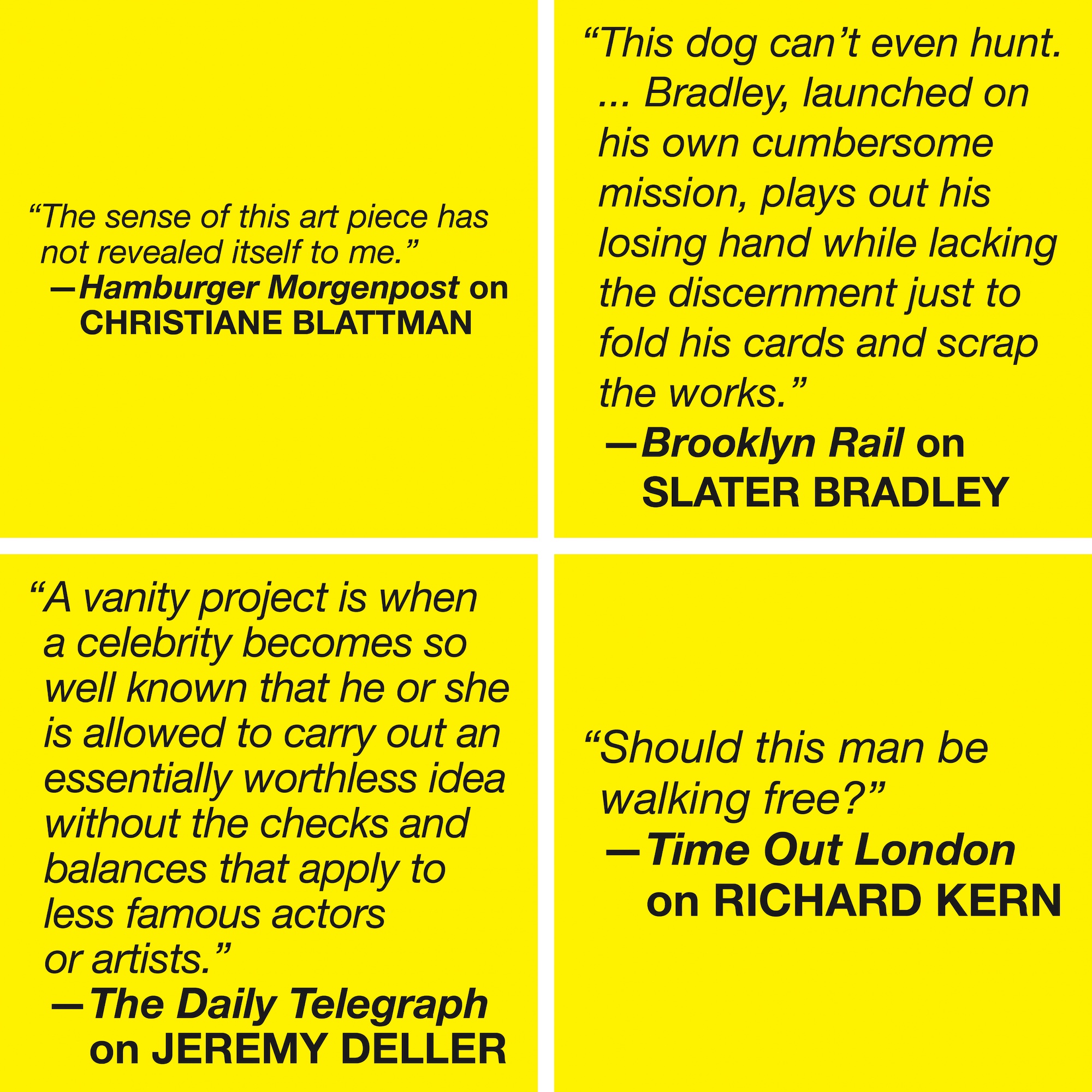

Is savage art criticism a dying art? Aleksandra Mir poses that question in Bad Reviews (Retrospective Press), co-edited with former Artforum editor Tim Griffin, which crowdsourced scathing reviews from 150 contemporary artists. The idea came when Mir first read critic Waldemar Januszczak’s rip-roaring review of a 2006 exhibition of young American artists at the Royal Academy in London. “This entire display stinks of stupidity and an absent education. Has anyone here read a book or studied history or looked at a Botticelli or questioned a technique or patiently thought their way through an artistic conundrum? Not a chance,” he barked in the Sunday Times. “This is a generation of paint-happy know-nothings brought up on hamburgers and porn, a talentless bloom of post-pop trailer trash.”

Mir asked hundreds of artists to send her their most brutal takedowns; the vast majority initially refused, unwilling to revisit the dark memories presumably stashed away deep inside their minds. As the project progressed, more warmed to the idea—Ed Ruscha, Mickalene Thomas, Florian Hecker, Carolee Schneemann, and Robert Longo all ended up contributing, resulting in a survey of art criticism’s most bloodthirsty takes arranged chronologically from 1963 to 2018. A product of meticulous research, Bad Reviews took seven years to assemble. Given the logistical nightmare of securing copyrights for print spreads and images, the book isn’t for sale—it will only be distributed to the artists and a selection of libraries and universities. (Mir encourages curious readers to find and distribute bootleg copies, however.)

The crowdsourced nature of Bad Reviews means it maintains a “for artists, by artists” perspective, a collective scrapbook of stinging opprobrium whose voice is ultimately hushed by design. “[Its] scattershot, artist-driven style is its appeal but also its limit,” curator Nick Irvin writes for Bomb. “The archive it presents is shaped more by artists’ hurt feelings than critical insights.” He notes how Gary Indiana’s influential Village Voice column is conspicuously absent while New York Times art critic Roberta Smith appears ten times. Alix Lambert, meanwhile, submitted a teenager telling her to kill herself via Twitter. The latter reveals an unfortunate reality about the state of publishing: many younger artists simply didn’t have scathing reviews from esteemed publications.

With the decline of print media and arts sections often succumbing to belt-tightening, there’s a growing scarcity of quality art critics wielding pen as sword. The art writing that ultimately ends up being published, Irvin notes, “leans more toward boosterism than critique, obliged to press releases and the publicity apparatuses that administer them.” The internet has also foisted a fractured content ecosystem on readers—some may view criticism from the old-guard buried behind algorithms as a positive, allowing new voices to enter the fold.

Mir notes that having one’s work beautifully scrutinized is a rite of passage—even if it hurts—and it’s becoming increasingly uncommon as the publishing industry evolves. “We’re now in a moment where social media likes, not even constructive positive arguments, are determining people’s credibility and significance, and of course anything negative is associated with hate,” Mir tells The Guardian, relishing in the heated debates that often unfolded in the ‘90s but feel absent today.

The author Raphael Rubinstein questions why art critics haven’t ventured beyond the written word given how accessible video technology has become. “I dream about what could be done in the realm of art criticism by someone with a sharp mind and a good grasp of Final Cut Pro,” he writes for Art in America, wondering if video essays about contemporary art may galvanize smartphone-wielding Gen Z-ers who may lack the attention span for text-based criticism. Videos certainly buoyed the career of Anthony Fantano, who reviews albums and songs on his YouTube channel The Needle Drop to more than two million subscribers, and was recently billed by the Times as “the only music critic who matters (if you’re under 25).”

If considered criticism—vicious or not—disappears, then the world will be deprived of gems like Pete Wells’ famous annihilation of Guy Fieri’s erstwhile American Kitchen and Bar. What could be sweeter than this one-liner: “Why is one of the few things on your menu that can be eaten without fear or regret—a lunch-only sandwich of chopped soy-glazed pork with coleslaw and cucumbers—called a Roasted Pork Banh Mi, when it resembles that item about as much as you resemble Emily Dickinson?”

Related Stories

PreviousARTAt Worthless Studios, Voice Art Takes Shape as an…ArtOrange County Gets a World-Class Contemporary Art…ARTBjörk’s New Album Is an Ode to MushroomsARTOld-Guard Auction Houses Are Embracing the FutureARTIST STATEMENTAn Electrified Canova Masterpiece Oozing With…ARTMeet the Makers Behind Remarkably Ornate Mardi Gras…ARTIST STATEMENTNate Lewis’s Dancing Figures Awaken a Sense of…CULTURE CLUBRyuichi Sakamoto and Krug Champagne Light Up the…ARTThe Art World’s Most Followed Shitposter Is Gaining…CULTURE CLUBStorefront for Art & Architecture Toasts 40 Years