Newly obtained data show that the U.S. government has detained more than 25,000 migrant children for longer than 100 days over the last six years.

In early June, a 17-year-old girl from Honduras got what she’d desperately wanted since she was 10: freedom from U.S. custody.

She’d been shuttled around the country for a good part of her childhood, living in refugee shelters and foster homes in Oregon, Massachusetts, Florida, Texas and New York — inexplicably kept apart from the grandmother and aunts who had raised her. Cut off from contact with her family, she had begun to self-harm and was prescribed a cocktail of powerful psychotropic medications. She hadn’t been taught English or learned to read or acquired basic life skills such as cooking. She hadn’t been hugged in years.

She finally made a choice: She asked to be deported, to live in a remote Honduran mountain village with her mother, who did not raise her. When she made the request, there was something the girl didn’t know: Her grandmother and aunts wanted to bring her to their home to North Carolina.

On that day in June, in the midst of a pandemic, she stepped off a plane in San Pedro Sula and into a world of poverty, violence and hunger. By then, anything looked better than another year in a U.S. immigration shelter.

The federal Office of Refugee Resettlement has a clear mandate: to hold children temporarily while it finds them a home, either with family or friends in the United States, or in foster care. But new data reveal that vast numbers of children have been stranded in custody for the long haul, living out a chunk of their childhoods in a government shelter system that’s at best ill-equipped to raise them and at worst a factory of abuse and trauma.

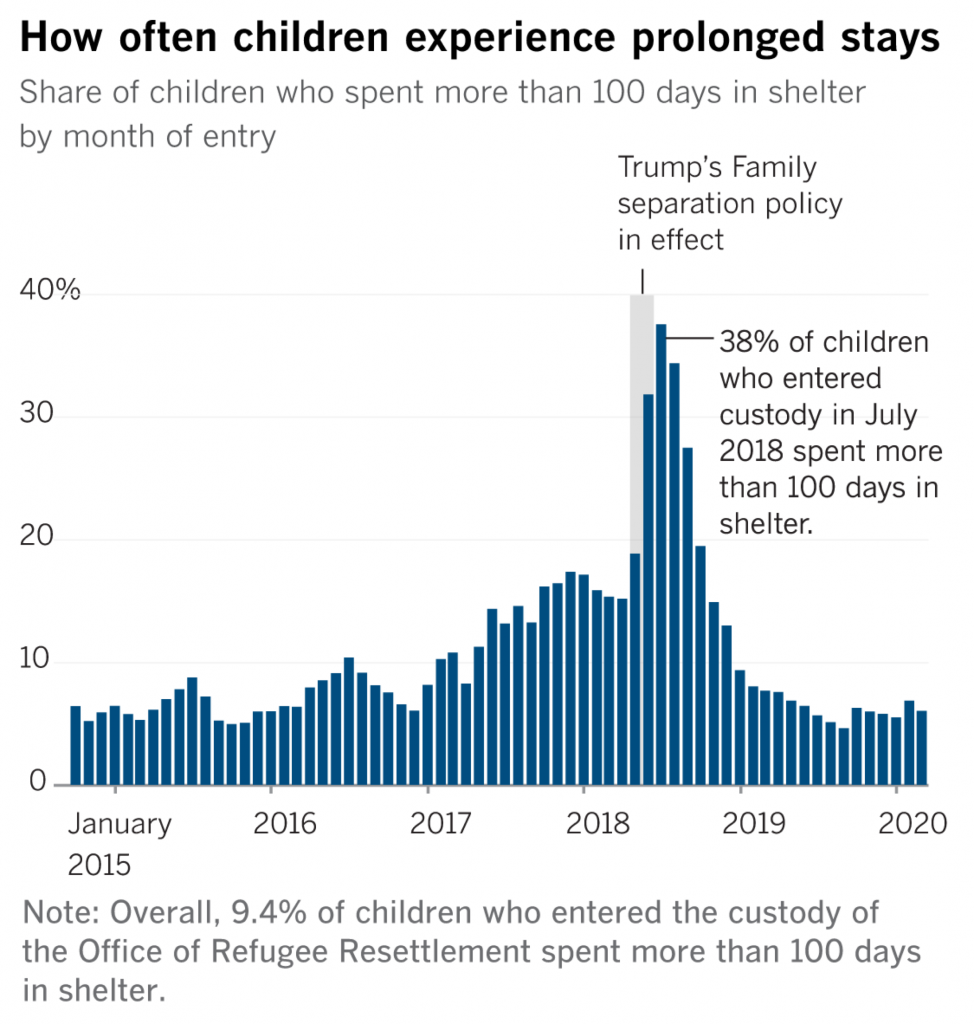

The data, obtained through a public records lawsuit filed by Reveal from the Center for Investigative Reporting, show that the U.S. government has detained more than 25,000 migrant children for longer than 100 days over the last six years. In that time, at least 266,000 children were held in government custody, the records show, meaning that nearly 1 in 10 of them experienced prolonged detention.

Nearly 1,000 migrant children have spent more than a year in refugee shelters. At least three children have spent more than five years in custody since 2013.

In some instances, pregnant teenagers gave birth while in refugee agency custody. New records reveal six babies born with U.S. citizenship were held for a year or more in shelters in Texas and Arizona.

“Your findings point to a systemic failure,” said Neha Desai, one of the attorneys in the landmark Flores agreement that sets the rules for government care of migrant children. In the 1997 settlement, the government agreed to release minors “without unnecessary delay.”

In response to criticisms of the Trump administration’s family separation policy, refugee officials have said they’ve reduced the average length of stay for migrant children in their custody. According to the agency, children spent an average of 66 days in the system in fiscal year 2019 before being reunited with family, placed with a sponsor or foster family, or deported.

The new government data show that most children placed into the custody of the Office of Refugee Resettlement since 2014 — 74% — were reunified with families in fewer than 66 days. But long-term detentions were not uncommon, dating to the Obama administration.

The data, which cover the final two years and four months under President Obama and the first three years and seven months of the Trump administration, show that lengthy detentions have accelerated under President Trump. They indicate that 7,401 children, or about 6%, who entered custody in those Obama years remained in the shelter system for more than 100 days. Under Trump, that number jumped to 17,676 and the rate of long-term detentions nearly doubled to 12%. In 2018, the height of family separation, more than 20% of children in shelters were held for more than 100 days.

Children placed in refugee agency custody are not accused of any crime. Yet government-contracted shelters are restrictive settings, ill-equipped to handle the long-term educational, emotional and social needs of children. Aside from the occasional field trip, every part of a child’s day — breakfast, school, counseling and recreational activities — takes place within the shelter.

Individual facilities adapt or modify local educational standards based on the average length of stay, according to the refugee agency. Former shelter workers describe a system of revolving classes, with little opportunity for academic advancement.

Children are typically deprived of access to cellphones, and computer use is highly limited. Short phone or video calls with family members are allowed twice a week, and only with the permission of shelter staff. Physical affection such as hugging is discouraged; the agency instead encourages fist bumps and high-fives.

In his final debate with Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden, Trump was asked about the 545 children who had been separated from their parents by the administration and never reunited. He defended their treatment, saying they “are so well taken care of. They’re in facilities that are so clean.”

But last year, the inspector general for the federal Department of Health and Human Services found that many migrant children arriving in the United States already had experienced intense trauma and that their trauma was compounded by the need to adapt to unfamiliar situations in shelters. The same report found that prolonged stays burdened children with additional stress and anxiety.

“One mental health clinician explained that even children who were outgoing and personable started getting more frustrated and concerned about their cases around the 70th day in care,” the report reads.

Many shelters also have documented histories of abuse, including sexual and physical assaults.

Yet there is no independent authority to which children can appeal their detention within the system, allowing them to languish indefinitely — or until they turn 18.

One 5-year-old from Angola entered custody in April 2019. He spent more than a year at the Heartland International Children’s Center in Illinois before he was deported in May.

A child from Guatemala who was 15 when he entered custody in February 2017 spent more than a year at a Texas shelter. He then was transferred to a center in New York, where he spent an additional 10 months. By the time he won his immigration case and was released, he had spent more than two years in custody.

The Office of Refugee Resettlement, a division of Health and Human Services that runs the contract shelter system, declined an interview for this story. In an unsigned statement sent by email, the agency said children in long-term custody represent only a slice of those in its care. The agency pointed out that some children pursue their immigration cases while in custody. And children who chose deportation may have longer stays because of the legal process.

The statement said that sometimes migrant children “have sponsorships that fall through, or the child otherwise chooses to pursue legal immigration relief while in ORR custody, which can account for a higher length of care.”

Records indicate that 368 children who ultimately were released to sponsors lived in agency shelters for a year or more. They also show that 1,893 children who spent longer than 100 days in shelters volunteered to be deported.

The Honduran girl confined for nearly seven years had arrived at the border in 2013, seeking asylum with her brother, an aunt and a cousin after her uncle was ambushed and killed in 2012. Because the girl and her brother did not arrive with their birth parents, the government separated them from their aunt. Reveal and The Times are not naming the children because they are minors.

The refugee agency placed the then-10-year-old girl and her 8-year-old brother in transitional foster care in Portland, Ore., while government contractors worked to reunite them with their family sponsor.

The relatives the girl had been raised by in Honduras — her grandmother, aunts and cousins — were by then living in North Carolina. The girl’s aunt had applied to be the children’s sponsor and the family members had expected they would be reunited as soon as the children were processed.

The family had successfully sponsored other children who were in Office of Refugee Resettlement custody. The family prepared papersand was in regular contact with agency staff by phone; documents show the government was poised to release the children to their relatives in October 2014.

The children instead were placed in a long-term foster care program in Massachusetts that same month.

It was around this time that the girl began to harm herself, the family said. The family in North Carolina recalls the previously cheery girl sharing that she would cut herself and bang her head against a wall. One family member said the girl believed it would get her out of custody sooner.

Sometime later, the calls from case workers stopped, without explanation, and the family was unable to reach either child. The relatives wouldn’t find out what happened to them for five years.

The girl’s grandmother, who goes by Doña Amalia, said she didn’t know what had happened to the girl and her brother. She said she prayed for them morning and night for years.

“It’s as if they were dead. We knew nothing. Nothing,” she said. Reveal and The Times aren’t using her last name because the family fears retribution.

The girl, meanwhile, was separated from her brother. He was placed with a foster family and now has permanent residency in the U.S. And she grew to believe that her grandmother, aunts and cousins had abandoned her.

During her time in custody, the girl was prescribed a number of different powerful psychotropic drugs, according to her and her family. Family members, including the aunt named on government documents as her sponsor, said they were never consulted.

The girl was placed at the Shiloh Treatment Center in Texas twice, first in July 2015 for about two years and again in May 2018 for about a year.

At the time she was there, children alleged in federal court filings that they were held down and drugged at the center against their will — and without their parents’ consent. A federal judge found that conditions at Shiloh violated the Flores settlement and ordered the federal government to release migrant children from the facility in 2018, citing allegations of physical abuse and overmedication. But the new records indicate that 61 children have been placed at Shiloh since that order, most recently in June. There have been no allegations that the Honduran girl was subjected to physical or sexual abuse there.

The short-term shelters offer little access to a meaningful education while depriving children of the ability to learn basic life skills or form close human ties.

During her time in refugee agency custody, the Honduran girl never spent more than 2½ years in any placement at one time. With each new stop came a new group of lawyers and social workers to pick up her case.

Marcela Cartagena, a former youth care worker at the Oregon shelter where the girl most recently lived, said teachers had three months’ worth of material. Those children whose length of stay was longer had little chance of their education progressing.

The agency said that it requires shelters to “develop curricula and assessments, based on the average length of stay” and that educational opportunities include “independent study, special projects, pre-GED classes and college preparatory tutorials.”

Daisy Camacho-Thompson, an assistant professor of psychology at Cal State Los Angeles, said it’s difficult to estimate the effects of prolonged detention on children.“I don’t know that we know en masse what happens to children educationally, cognitively and socially when they are without the outside world for a year, without a family, without the ability to learn their values through their routines and daily activities, because we don’t have a lot of examples,” Camacho-Thompson said.

The girl’s most recent government-appointed attorney, Caryn Crosthwait, submitted her request to be deported. Judge Richard Zanfardino granted the petition. Both declined to be interviewed.

The child would be sent to one of the most dangerous countries in the world, to live with the mother she barely knew.

No one at the hearing in January mentioned that the women who’d raised her — and wanted to continue raising her — were living in the United States.

Outside the hearing, a reporterfor Reveal informed the girl that her family was still in the United States and wanted to bring her home.

She stopped and looked down at photographs of family members she hadn’t seen in years.

She was shocked.

“It’s them,” she told Isabel Rios, the caseworker who chaperoned the girl to immigration court.

Rios rushed the girl away. Within a few days, the girl called a number written on one of the photographs and reached her family in North Carolina. She sounded confused at first, they said, but eventually told family members that she wanted to live with them.

The mother, reached in Honduras before the girl was deported, said the same thing: The girl told her that she wanted to be reunited with her grandmother and aunt in North Carolina.

“They’re the ones who raised her,” said the mother, who added that she also wanted the girl to stay in the United States.

The next month, Sen. Jeff Merkley (D-Ore.) pressed Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar about the girl’s case at a Senate Appropriations subcommittee hearing. “We want kids with us for as short a time as humanly possible, consistent with their safety, so I will dig in on that personally,” Azar testified.

“I want to make sure she’s treated fairly and her family’s treated fairly,” he told Merkley.

A little more than three months later, the girl was deported.

In an email, Health and Human Services spokeswoman Katie McKeogh declined to comment on whether or how Azar sought to help the girl, who was in his agency’s custody for six years, seven months and two days.

Reveal obtained a psychological evaluation of the girl that was performed in February. “Given the limitations of her intellectual abilities, she is at risk for faulty social judgment and being manipulated or exploited by others,” it reads.

After being deported, the girl was briefly placed in a shelter for children returning to Honduras, where she was quarantined because of the pandemic.

She eventually made her way to her mother.

Reached by phone, the girl said her mom had badly beaten her. She said she didn’t have decent clothes to wear or food to eat. Local community members, some of whom witnessed her eating food from garbage piles, lent her clothing and a pair of flip-flops, she said, but she has no real place to call home.

In an interview last weekend, her mother acknowledged that she did whip her daughter for talking back, but said the girl also harmed herself, slamming her head and body against walls. The mother said that she was never told the girl had an intellectual disability and that she found it difficult to control her.

The girl said she had met a 22-year-old man from a neighboring village and plans to marry him. Her mother said she threw away the medication her daughter had taken for years in the United States, because it had expired. The girl said she didn’t want to take the medication anyway.

The girl said she had longed to be reunited with her family in North Carolina. She recalled being told by officials that the family there didn’t have enough room, food or resources to care for her. Meanwhile, the family prepared and waited for years for her to return home.

She was adamant that she never wanted to return to a shelter.

“Over there, you weren’t allowed to have a boyfriend, or give someone a kiss, or a hug, or a letter,” she said. “You couldn’t share clothes, or even a hairbrush or soap. None of that.”

After almost seven years in and out of the shelter system’s educational programs, the girl struggles with basic English. She missed out on a structured education during the times most kids are in grades 6 through 12.

“The only thing they taught me,” she said, “was vowels and the alphabet.”

Bogado and Lewis write for Reveal.