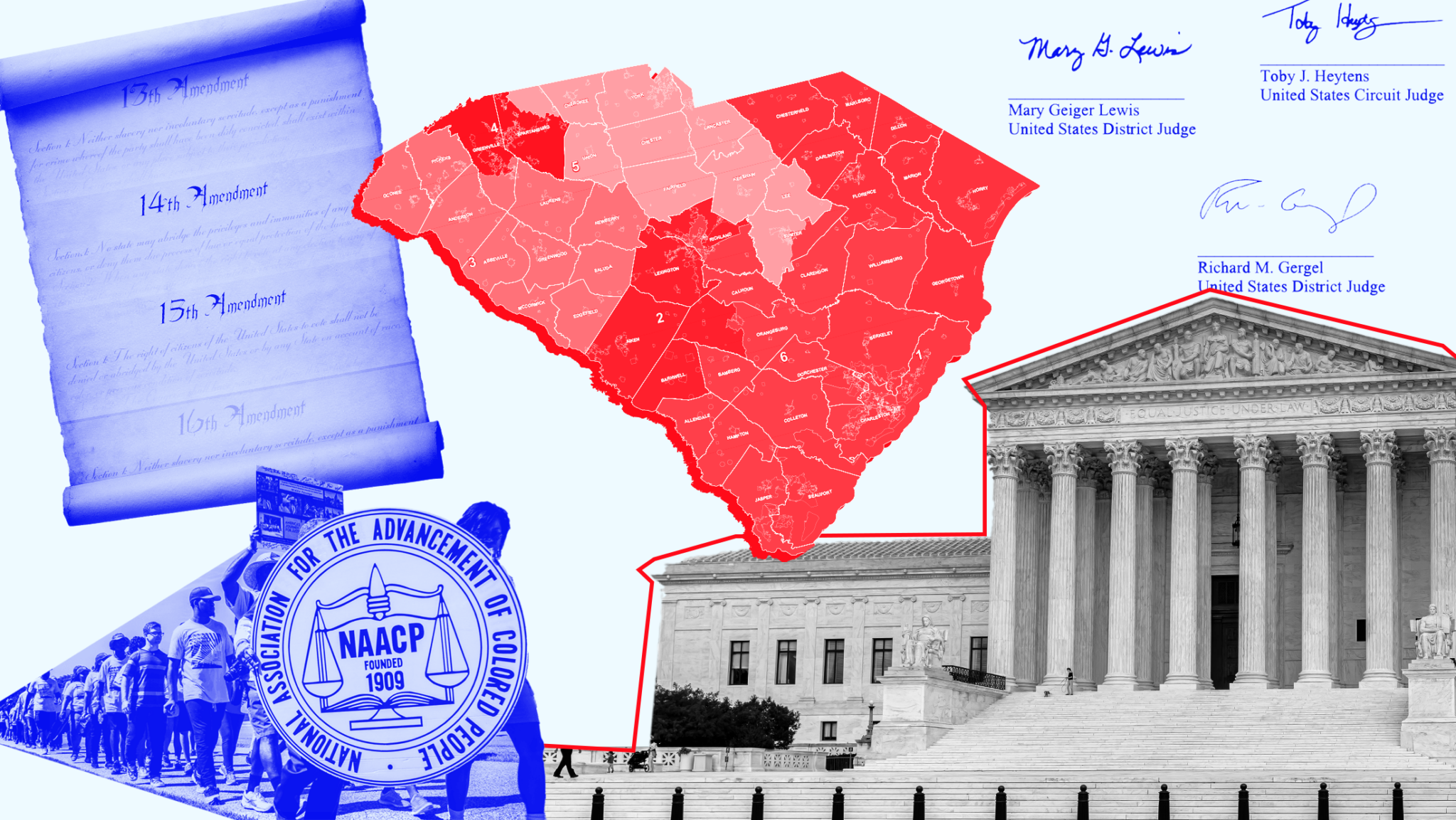

On Monday, May 15, the U.S. Supreme Court announced that it will hear a racial gerrymandering case out of South Carolina — Alexander v. South Carolina Conference of the NAACP — during its next term. Previously, a three-judge panel struck down South Carolina’s congressional map for being an unconstitutional racial gerrymander. Racial gerrymandering occurs when map drawers use race as the predominant factor to assign voters to districts without a compelling reason to do so. In agreeing to review this case, the nation’s highest court will decide the fate of South Carolina’s congressional map and potentially impact the future of racial gerrymandering claims.

After the release of 2020 census data, the South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP sued over South Carolina’s new congressional and legislative maps.

In October 2021, following the release of 2020 census data, the South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP and a voter filed a lawsuit challenging the state’s congressional and legislative maps for being malapportioned, meaning the maps were outdated and did not account for the state’s newly updated population data. After the South Carolina Legislature enacted new legislative and congressional districts drawn with updated 2020 census data, the plaintiffs filed an amended complaint alleging that these maps were racially gerrymandered and limited the voting strength of Black voters in violation of the 14th and 15th Amendments of the U.S. Constitution.

The parties negotiated an agreement about the state House districts, leaving only the congressional map to be resolved by litigation. In their most recent amended complaint, the plaintiffs argued that South Carolina’s 1st, 2nd and 5th Congressional Districts were racially gerrymandered in violation of the 14th and 15th Amendments. The plaintiffs alleged that the “Legislature chose perhaps the worst option of the available maps in terms of its harmful impact on Black voters that it proposed or were proposed by members of the public.”

The plaintiffs explained: “Again and again, the South Carolina General Assembly assigned and reassigned voters differently depending on their race: communities with predominantly Black populations (like Sumter, Orangeburg, Richland, and Charleston counties, and the cities of Columbia, Sumter, and Charleston) were all cracked—preventing Black voters from electing candidates of choice (or otherwise influencing elections), while communities with predominantly white populations (like Beaufort and Lexington counties and Sun City) were kept or selectively made whole to fortify white voting power in six districts.”

In January 2023, a three-judge panel issued a unanimous decision striking down South Carolina’s congressional map.

Since the plaintiffs challenged the constitutionality of the South Carolina congressional map under the 14th and 15th Amendments, federal law requires a three-judge panel to hear the claims instead of a single district court judge. Following an eight day trial held in October 2022, a three-judge panel ultimately struck down the configuration of the state’s 1st Congressional District, represented by Rep. Nancy Mace (R), after finding that it was an unconstitutional racial gerrymander in violation of the 14th Amendment. The panel further concluded that the district was created with racially discriminatory intent in violation of the 14th and 15th Amendments.

“After carefully weighing the totality of evidence in the record and credibility of witnesses, the Court finds that race was the predominant motivating factor in the General Assembly’s design of Congressional District No. 1 and that traditional districting principles were subordinated to race,” the opinion stated. While the panel concluded that South Carolina’s 1st Congressional District was an unconstitutional racial gerrymander, it did not find that the state’s 2nd or 5th Congressional Districts were unconstitutional.

In its January opinion, the three-judge panel explained how Black voters were effectively stripped from South Carolina’s 1st Congressional District: “In Congressional District No. 1, Charleston County was racially gerrymandered and over 30,000 African Americans were removed from their home district.”

The panel found that creating South Carolina’s 1st Congressional District would have been “effectively impossible without the gerrymandering of the African American population of Charleston County” and that the “movement of over 30,000 African Americans in a single county from Congressional District No. 1 to Congressional District No. 6 created a stark racial gerrymander of Charleston County.”

case page South Carolina Redistricting Challenge

At the end of 2021, after the South Carolina Legislature enacted new legislative and congressional districts, the South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP and a voter filed amended complaints alleging that the new state House and congressional maps are racially gerrymandered and limit the voting strength of Black voters in violation of the 14th and 15th Amendments.

South Carolina Republicans appealed this decision to the U.S. Supreme Court, which will review this case during its next term.

Any decision from a three-judge panel involving claims under the U.S. Constitution is directly appealable to the U.S. Supreme Court, which must accept the appeal and issue a decision. In this case, South Carolina Republican officials — including state legislators and members of the state’s election commission — appealed the panel’s January decision to the Supreme Court and asked the Court to reverse the decision. On appeal, the GOP legislators arguethat the panel’s decision should be reversed because the panel did not presume the Legislature acted in “good faith,” “failed to disentangle race from politics” and otherwise erred in its findings.

On the other side, the plaintiffs argue that the Supreme Court should affirm the panel’s decision. “This evidence, on top of evidence that mapmakers adopted a racial target and made ‘dramatic’ changes to hit that target—coupled with Defendants’ non-credible denials—reinforces the soundness of the panel’s racial predominance finding,” the plaintiffs assert.

In a recent press release the plaintiffs stated: “For too long, our state’s electoral process has silenced us and severely weakened the ability of our communities to be fully and fairly represented and accounted for. South Carolina’s congressional map is the latest instance in our state’s long, painful history of racial discrimination that must be remedied.”

The stakes of this case are extraordinarily high for both South Carolina and voters nationwide.

Previously, the Supreme Court has ruled that “a State may not use race as the predominant factor in drawing district lines unless it has a compelling reason.” It is no secret that the landscape today is different from that of even a year ago and that conservatives on the Court are increasingly hostile to protecting voting rights.

It remains to be seen if the Supreme Court’s conservative majority will adhere to its prior precedent and rule in favor of the voters in South Carolina or whether the Court will reverse the three-judge panel’s decision at the request of the South Carolina Republicans. If the Supreme Court reverses the panel’s decision and allows this racial gerrymandering to persist, voters, specifically Black voters in South Carolina who were targeted when these maps were drawn, will suffer. Moreover, voters in both South Carolina and across the country could be without yet another tool to challenge unfair and racially discriminatory maps. The Court’s decision to hear this case comes on the heels of a term in which the Court is poised to determine two major cases that could severely alter the landscape for voting rights and redistricting.

What happens next?

While we cannot predict the outcome of this case, we can shed a bit of light on what will happen next. In the near future, the Supreme Court will issue a scheduling order. The case will be briefed and “friends of the court” will file briefs in support of either side. The Court will hold oral argument in the case at some point during its term next fall and it will likely release its decision next year. In turn, the Court’s decision could have implications for the 2024 election cycle, especially if its decision alters the configuration of South Carolina’s congressional map in some way.