Following hours of angry and tense protests, UC Berkeley officials abruptly announced Wednesday afternoon that they would pause work on transforming historic People’s Park into housing “due to the destruction of construction materials, unlawful protest activities and violence on the part of some.”

The move was a victory for protesters, who had raced to the park soon after UC officials erected a fence around it early Wednesday morning.

In a statement, officials said safety is the university’s highest priority and that construction workers and law enforcement had been “withdrawn from the site,” which has long been a symbol of 1960s counterculture and which many view as hallowed community ground.

It was unclear what would happen next or when. University officials, who rushed to begin work just hours after a judge issued a ruling allowing it, said they would “assess the situation in order to determine how best to proceed” with construction of a project that would provide housing for students and homeless people.

Harvey Smith, president of the People’s Park Historic District Advocacy Group, said he was happy work had stopped but that officials never should have tried to commence it in the first place. “The legal remedies haven’t been exhausted,” he said, noting that his group had asked a court of appeal to halt construction Wednesday morning.

UC Berkeley and the city of Berkeley proposed redeveloping the park in 2018, calling it a first-in-the-nation plan to build long-term supportive housing for homeless people on university land. The university would also build 1,100 units of badly needed student housing.

Alameda County Judge Frank Roesch late Friday issued a tentative decision that UC Berkeley could begin clearing the historic park for construction work. He made that ruling official late Tuesday, and within hours, the university moved to erect fences and start site preparation. Almost immediately, workers were thwarted by protesters determined to halt their momentum.

Shortly after 2 a.m. as construction machinery moved in, the Twitter account “Defend People’s Park” issued an urgent call to activists to head to the area. “WE NEED SUPPORT,” the tweet read. “PLEASE COME.”

By early Wednesday morning, protesters were confronting police and construction crews, shaking the metal fences, with some jumping over the structures to be tackled by California Highway Patrol officers.

A tense standoff ensued for several hours as crews cut down trees and police tried to keep protesters at bay.

One of the protesters had his hand bloodied while trying to break through the fence. “How will your grandchildren feel about this?” he yelled at the officers. “You are a bunch of fascists!”

Behind the officers, crews used chainsaws and other equipment to cut down old trees on the property, with the crowd shouting anguished yells with each one that hit the ground.

“This is horrible,” said Elana Auerbach, a Berkeley resident who showed up in support of the protesters. “Our city claims to believe in equity and climate resilience, and I’ve just seen dozens of trees felled.”

While officers and protesters jostled in the background, Auerbach and others passed out fliers urging supporters to come to a rally for the park starting at 5 p.m.

By about noon, the university had made the decision to retreat. The crews departed, police dispersed and protesters broke through the fences and reoccupied the property. An hour later, protesters had dismantled much of the fencing, lobbing the metal segments on surrounding streets, with one yelling: “Save People’s Park!”

Not everyone at Wednesday’s protest was opposed to UC Berkeley’s plans. Various onlookers watched from the sidelines.

Drew Nguyen, a PhD student at UC Berkeley, said he felt “caught between a community of students” who support the protesters and others who feel no connection to the park and the activists and unhoused people who made it their home. Many UC students, he said, are similarly divided, wanting more housing options in Berkeley but aware that People’s Park is a treasured expanse of greenery.

On Thursday, UC Berkeley said that seven people had been arrested in the melee on suspicion of battery of a peace officer and other charges. Two officers were injured and one person released from custody after being arrested and was taken to the hospital with minor injuries.

Four groups had filed lawsuits against the university’s plan, including the People’s Park Historic District Advocacy Group and Make UC a Good Neighbor. They argued, among other things, that the university had other options for developing housing and had not adequately studied them, as required by the California Environmental Quality Act.

Judge Roesch disagreed, with UC Berkeley saying it would attempt to balance nature, history and the need for housing. “The project will preserve more than 60% of the site as revitalized green space,” the university said in a statement, and will include a memorial to the park’s historic significance.

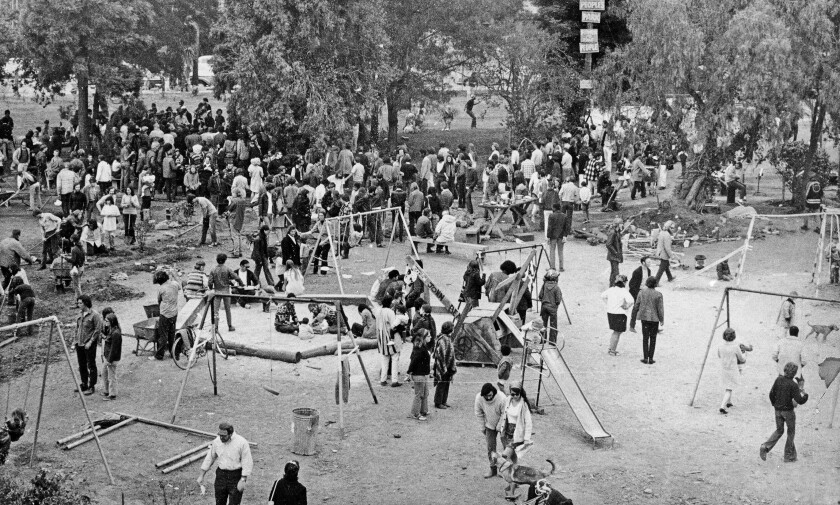

People’s Park was born in 1969, when the university announced a plan to develop the land, which is about four blocks south of the Berkeley campus just east of Telegraph Avenue.

Furious at the proposed development, hundreds of people dragged sod, trees and flowers to the empty lot and proclaimed it People’s Park. In response, UC erected a fence. The student body president-elect urged a crowd on campus to “take back the park” and more than 6,000 people marched down Telegraph to do just that. A violent clash ensued, leaving one man dead and scores injured.

While embraced by many Berkeley residents as a city institution, others saw the site as a blight and unsafe for nearby residents. The park was added to the National Register of Historic Places in May. Although the Berkeley City Council had once opposed development, the current council supports the university’s plan.

In recent years, and especially during the pandemic, the park became an encampment for unhoused people and those with other troubles. “This place became a sanctuary,” Auerbach said. “There was nothing else like it in the city. It had an incredibly welcoming feel.”

Working with the city and nonprofit groups, the university offered transitional housing to residents of the park for up to a year and a half, as well as meals and social services.

A few unhoused people could be seen camping in the park Monday morning, but the numbers were far down compared to previous months.