The Kremlin has stamped out public dissent but makeshift memorials to Ukrainian dead are a focus for those opposed to the conflict

Natalia Samsonova says she imagines the muffled screams of those trapped under the rubble, the fire and smell of smoke, the grief of the mother who lost her husband and infant child beneath the ruins of the building in Dnipro bombed by Russia. She imagines being unable to breathe.

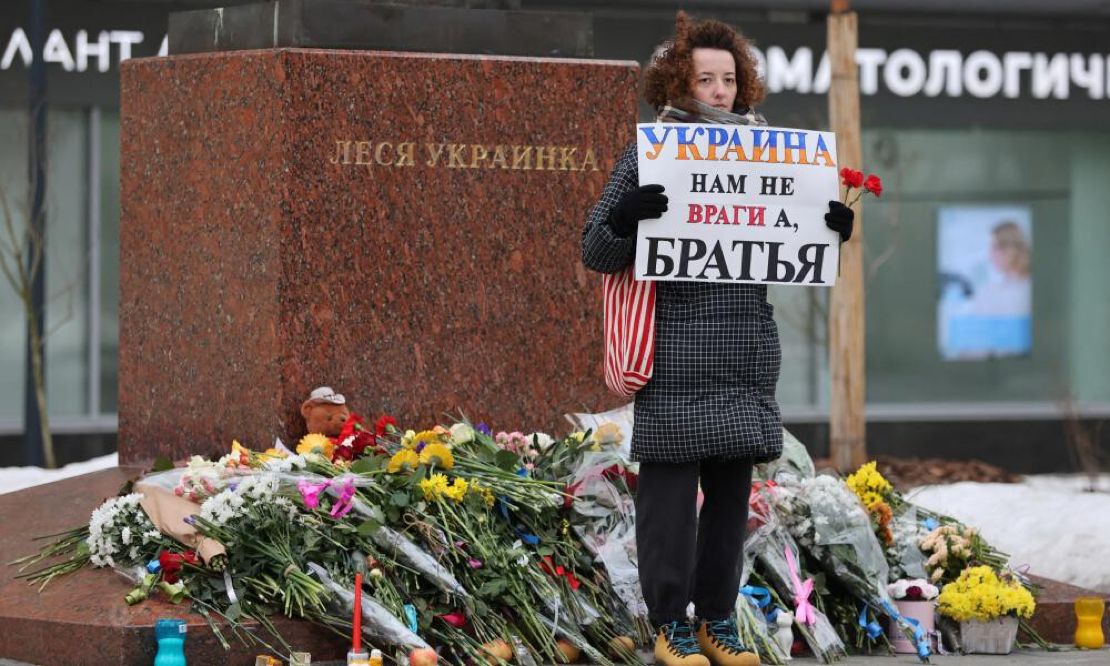

That is why she is here, at a statue to the Ukrainian poet Lesya Ukrainka, a largely unknown monument tucked away among Moscow’s brutalist apartment blocks that has hosted a furtive anti-war memorial at a time when few in Russia dare protest against the conflict.

“I don’t know what else I can do … I wanted to show that not everyone is indifferent [to the war] and that some people still have a conscience,” she says, her eyes filling with tears. It is the second time she has returned to place flowers at a makeshift memorial to victims of the strike on 14 January that killed 46 people and wounded more than 80. She passes it when she comes to visit her mother, who lives nearby.

This is the closest Russia comes to an anti-war demonstration these days. While Vladimir Putin’s announcement of the invasion of Ukraine brought thousands on to the streets last February, the government has methodically stamped out public dissent, arresting thousands and pressuring many more to flee the country.

Now, more than 10 days after the missile strike in Ukraine, a trickle of Muscovites still come to pay respects to those who died. An elderly man silently bows to the statue and crosses himself as he passes. Returning from class this week, Ilya, a student, bent over to read the memorials left at the statue.

They included an image of the destroyed building in Dnipro and a sign that said: “Ukraine, we are with you!”

But most people go past, waving off a reporter asking questions about the war. For days, a police car with lights flashing has been parked next to the statue, warning off those willing to pay their respects with the threat of arrest or worse.

“There is no place to oppose or even to grieve or pray for the dead,” says Ilya, pointing at two officers standing near the statue. “The pressure … is too much. It will explode.”

It is not an idle threat. Last week, a woman was arrested near the statue for holding up a sign that said “Ukraine is not our enemy, they are our brothers”. On Friday a court upheld the arrest of Ekaterina Varenik for “resisting arrest”. “All the forces of evil were against Ekaterina today,” her lawyer said.

As Russia’s invasion of Ukraine approaches its first anniversary, the Kremlin appears resigned to plunge deeper into a war that has already left tens of thousands dead.

Last week western countries approved a military aid package that will send hundreds of armoured vehicles, as well as Leopard and Abrams main battle tanks, in a clear signal that the west is committed to helping Ukraine defend itself and regain its territory from Russian occupation.

More than 100,000 Russian military personnel are believed to have been killed or wounded since the beginning of the conflict, leading to the country’s first mobilisation since the second world war. Hundreds of thousands have been sent for military training and eventual deployment to Ukraine, while hundreds of thousands more have fled the country to avoid the draft. A second mobilisation is rumoured in the coming months.

Russia has brushed off the promises of military aid while accusing the west of “direct involvement” in the conflict, saying that “tensions are escalating”. As to the tanks, a Kremlin spokesperson said they would “burn like the rest”.

Both sides are believed to be testing the chance for a new offensive in the spring that they hope will lead to a decisive breakthrough. In advance, Russia has continued its strategy of launching salvoes of guided missiles and “suicide” drones to target civilian infrastructure, cutting power and heat to Ukrainian cities amid subzero temperatures.

It was an inaccurate X-22 anti-ship missile that slammed into the block of flats in Dnipro on the afternoon of 14 January in one of the deadliest single strikes since the war began. Pro-Russian activists heckling mourners at the makeshift memorial in Moscow have echoed the official explanation: that the missile only hit the building because it was struck by Ukrainian air defences.

In response to the strike, small groups of Russians began to organise memorials in cities around the country: at a statue to Ukrainian writer Taras Shevchenko in St Petersburg, a bust to the same writer in southern Krasnodar, and at a memorial to the victims of political repression in the Ural city of Yekaterinburg. The memorials are routinely cleared by municipal services but reappear the next day.

As Samsonova speaks, two police officers watch from their car, a reminder that even such an innocuous challenge to the war is seen by the government as a threat.

“This is the least one can do,” says Samsonova. “To be a person, to extend your condolences. I fear the longer this goes on, the more people will forget what it means to be a person any more.”