Contracting COVID-19 is putting already financially stressed Americans on the brink of economic disaster. And the rest of the country isn’t that far behind.

Of the Americans who’ve contracted COVID-19, 63% are facing serious financial problems, according to a survey released Wednesday morning from NPR, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Those who haven’t gotten sick aren’t faring much better: 46% of households in the U.S. reported serious financial problems because of the pandemic in the survey, 31% have used up all their savings and 21% are having trouble paying debt.

The high percentages of financial distress shocked researchers, said Robert J. Blendon, an emeritus professor of health policy and policy analysis at Harvard who worked on the survey.

“We were completely surprised,” said Blendon, who has done other polling around natural disasters.

For this survey, researchers asked if Americans had “serious” financial Issues as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. Typically in the event of a hurricane or flood, government aid is there to provide a cushion for those in distress, which limits the number of people who report “serious” issues. Blendon and his fellow researchers assumed that the stimulus checks and expanded aid provided in the economic stimulus package, called the CARES Act, would cushion the blow of the pandemic. They expected to find what they normally see after a disaster: a small subset of people for whom that cushion wasn’t enough.

Instead they found widespread, serious financial distress ― particularly among Americans earning less than $100,000 a year, people of color, those with disabilities and those who’ve contracted the coronavirus. The numbers are jaw-dropping for nonwhite Americans: 72% of Latino households reported serious financial problems; so did 60% of Black households and slightly more than half of Native Americans.

Desirae Hernandez, a 39-year-old home health care worker, said she did everything she could to keep from getting sick while she worked through the pandemic, but she wound up contracting the virus from a client. She was out of work for four weeks, with only six hours of sick leave.

Everyone in her home in Kennewick, Washington, got sick, too. Her husband, who was already working less because of the coronavirus shutdowns, was out of work for weeks with COVID-19. Hernandez’s 9-year-old son contracted the virus, as did her mother-in-law. Hernandez’s brother- and sister-in-law were both hospitalized.

“It was all around a scary situation,” she said. “Financially, I’m still catching up.”

They paid only the bills they had to pay and went to the food bank. Her cellphone was shut off. So was the Internet at home. She paid a neighbor $20 to borrow WiFi so her young son could attend online school. Luckily, Hernandez has insurance through the health care arm of the Service Employees International Union.

Now everyone is feeling better, but the financial pain lingers. Hernandez says she has $3.94 in her checking account.

“At least it’s not in the red,” she said with a laugh.

The Harvard survey, for all the distress it shows, could even be painting a fairly rosy picture, as it was conducted in July and August just as the financial benefits of the CARES Act expired. Researchers surveyed a national representative group of 3,454 adults, ages 18 and over, both online and by phone, asking a range of questions about the effect of the coronavirus on their household finances, jobs, health care, housing, caregiving and other measures of well-being.

Early on in the pandemic, lawmakers passed three stimulus packages, the largest was the $2 trillion CARES Act in March. It provided $1,200 one-time payments to most Americans, with some households getting even more, expanded unemployment insurance to include those not traditionally covered, such as gig workers, and it beefed up unemployment payments with an additional $600 a week for jobless workers so they could afford to stay home and ride out the storm of the pandemic. But those payments expired. And the stimulus checks were spent.

Part of the issue is that policymakers didn’t realize the crisis would go on this long. “There was a belief it would be over sooner,” said Blendon, who added that there was little familiarity with the disease. So there was a lack of awareness that some would suffer long-term disability from COVID-19. These people should be getting help from the government, so they can have enough time to recover, he said.

Though Congress and the White House have discussed additional relief and stimulus, and the House actually passed a $3 trillion relief bill in May, it hasn’t happened, and a political war over the confirmation of a new Supreme Court justice could distract from the matter.

Blendon said it was clear that whatever aid the CARES Act provided, it was inadequate. He was incredulous that the benefits had expired and that there was no more aid coming.

“We have this incredible number of people who are very financially stressed and vulnerable, and it’s affecting their ability to educate their kids at home. For whatever reason, this aid is not going to be continued.”

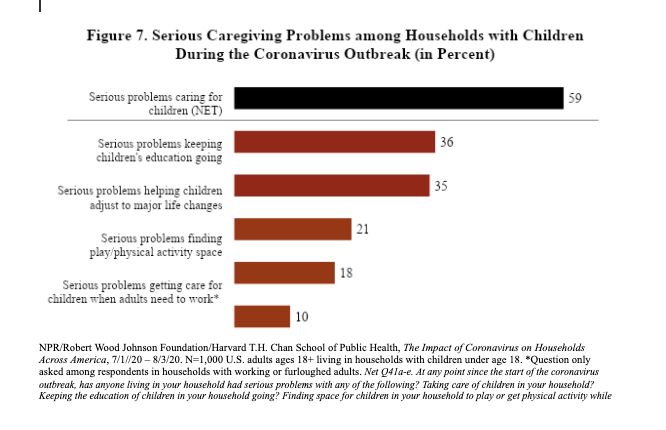

Most parents are struggling to care for school-age children, who are doing virtual classes, while trying to keep their jobs. The Harvard survey found that 59% of households with children are having serious problems caring for them, including 36% where there is difficulty with keeping the kids in school at all.

In households where someone has contracted COVID-19, the situation is more dire. In households with kids younger than 18 where someone contracted the coronavirus, 87% of respondents said they’ve faced serious problems caring for their children.

Hernandez said that caring for her son, whose school is online this year, is still a challenge. She and her husband are back to work, and there’s no one home during the day. Getting child care isn’t easy when you’ve had the coronavirus.

“Nobody wants to watch a kid that just had COVID,” she said. “The last place you want your kid to be is where they’re not wanted.” So far, she’s been able to rely on a niece for child care.

Nearly 2 in 3 households where an adult has been sick with the coronavirus has experienced job loss, furloughs or a reduction in hours, according to the survey. About half of the coronavirus-affected households have used up their savings and are facing serious problems paying credit cards or other debt. And about 1 in 5 of these households are having problems affording medical care.

Jennifer English, a 46-year-old mother of three living just outside of Portland, Oregon, blew through her savings over the past 170-plus days that she’s been dealing with the coronavirus. She got sick in March, when she sat down for a taco dinner with her 15-year-old son and noticed she couldn’t taste the carne asada.

“I had just watched a CNN episode about how loss of taste was a symptom, and I just knew I had it,” she said. “I felt like my world crashed around me after two bites of a taco.”

Things got worse from there; multiple trips to the hospital, fever, a dizzy spell so intense she fell onto the bathroom floor and was stuck there for hours because no one was home with her.

Pre-pandemic, English had two jobs and was running ultra-marathons. Now she says she can be up and about for only a few hours a day before becoming exhausted. She counts herself among the COVID-19 “long-haulers” experiencing debilitating symptoms. She has dizzy spells and shortness of breath. All that was exacerbated recently when she and her family had to evacuate their home because of the fires raging out west.

Recently, English was told she could return to one of her jobs, at a restaurant, but says she’s still too sick to work. Her other job, running a restaurant at a nearby convention center, is still on ice because of the pandemic.

She was getting unemployment for a time, but the payments just ran out. “I probably have enough to pay the mortgage next month, but no food or bills,” she said. “I’m a wreck to be honest with you. I’ve had breakdowns, throughout this.” She emphasized that she was never like this before. “I’m that girl at work that annoys everyone because I’m always in a good mood. It’s been devastating. I’ve learned to just let the tears flow. It’s not doing me any good.”

Her children just started online school, and English is counting her blessings that her husband, who is out of work right now, is home with her and able to help the 6- and 7-year-olds attend virtual school.

English thought she’d be better by now and is hopeful that she’ll be able to return to work soon. “This whole time I’ve been thinking, this can’t last much longer.”