After Margie Allen’s son Ryan was murdered on Thanksgiving in 2020, she said police in Jackson, Mississippi left it up to her to find clues.

“I was shown a picture of my baby on the side of the road. I was shown some information. And I was told to go solve my own crime,” Allen said.

Mothers facing the prospect of investigating their own child’s murder has become a reality in Jackson, where a homicide squad of eight detectives responded to 156 homicides last year. Jackson suffers from one of the highest murder rates in the country, and roughly four in 10 of those killings went unsolved.

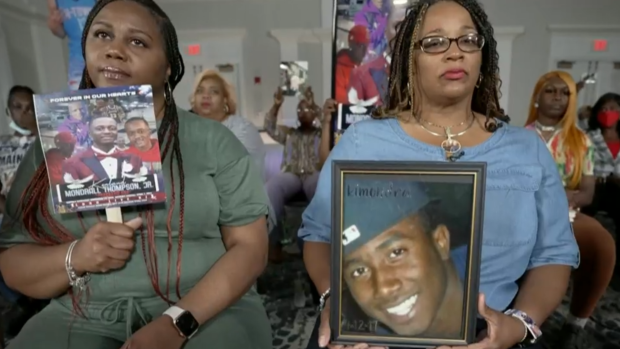

BS News interviewed nearly three dozen people who lost loved ones to murder in Jackson, and found widespread frustration that more hasn’t been done to track down the killers of their children. They said they felt their cases weren’t priorities to the police in Jackson.

“Murder is at the bottom of the totem pole. A young Black male’s gonna die tomorrow. We have three over the weekend. We can’t get to you right now,” Allen said.

Many expressed frustration with their communications with the police — even Willie Mack, a former Jackson homicide detective with 24 years on the force, whose daughter was shot to death in 2017.

“Every detective I talked to, they hung the phone up in my face,” Mack said. “I don’t get no calls returned.”

Jackson’s mayor, Chokwe Antar Lumumba, has personal experience with the pain of an unsolved shooting. As a child, his brother survived being shot in the head — a crime that never led to an arrest.

“I will always tell you that the Jackson Police Department can do a better job,” Lumumba said, adding that the city has a shortage of police officers. The FBI says a homicide detective should oversee five cases a year. The Jackson Police Department has eight full-time detectives, enough to handle 40 murder investigations — about one-quarter of last year’s homicides.

“They’re certainly inundated,” Lumumba said.

Jackson Police Chief James Davis says the problem goes beyond staffing at the local level. Davis said his department depends on an overwhelmed state crime lab for evidence processing.

“The whole system is backlogged. I could use more police officers. I could use more homicide detectives, but if the state is backed up, the court is backed up, we will still have the same problem by developing these cases that we’re already doing,” Davis said.

Adam Gelb, president of the nonprofit Council on Criminal Justice, said many police departments don’t devote enough resources to detective work.

“What we need is a real commitment to investigation, a real investment in the investigative and forensic resources,” Gelb said. “We need more investigators on the case within the first 48 hours when the case is hot.”

To many of the relatives of murder victims who spoke to CBS News, the work of the homicide squad was moving too slow. Detective Kevin Nash defended the department from an office where stacks of murder case files covered every desktop.

“I call them back when I’m available,” Nash said. “It may not be right then when they want to. And remember, if this was your child, you want immediate answers, too.”

Three weeks after CBS News visited Jackson, police arrested three people in connection with Ryan Allen’s murder. The Jackson Police Department said in a statement that “the investigation never went cold.”

“We continually followed up on tips, leads, and the things Ms. Margie Allen asked us to follow-up on,” the department said.

Allen said she thinks police became more motivated to solve the crime after being pressed by CBS News.

“You just lay in bed at night and just cry all night. And you get up and try to fight more to get justice for your child,” she said.