One Virginia community college is dropping from its name John Tyler, the 10th president of the United States who backed the Confederate rebellion before he died. Another is ditching Thomas Nelson Jr., a signer of the Declaration of Independence and prominent military and political leader who historians say enslaved hundreds of people of African descent.

A third has inserted an ampersand to emphasize that Patrick & Henry Community College is named for a pair of counties it serves in the southern region of the state. The tweak is meant to distance the two-year college previously known as Patrick Henry from the famed Revolutionary-era orator of that name who was also an enslaver.

These and other name changes within the Virginia Community College System reflect the breadth and persistence of the racial reckoning in higher education since the murder last year of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer. The national movement for social and racial justice led to fresh scrutiny of names honored in each of the system’s 23 colleges. In a state with a long and painful history of slavery and racial oppression — alongside a vibrant tradition of public higher education — there was much to consider.

Passions flared. Critics of the renaming process protested what they saw as political correctness run amok. Proponents said it helped the schools align with their public mission.

John Tyler Community College, near Richmond, is transitioning over the next several months to Brightpoint Community College. Thomas Nelson Community College, in Hampton, is becoming Virginia Peninsula Community College.

“We enroll lots of people whose ancestors were enslaved, were marginalized, were clearly taken advantage of,” said Glenn DuBois, the system’s chancellor. “And what do you say to those students when they’re looking at some of these names?”

DuBois pointed to Lord Fairfax Community College, based in the northern Shenandoah Valley and Fauquier County. Its name honors a hereditary title held for centuries by a British family, including an 18th-century man, Thomas Fairfax, who was an influential figure and enslaver in colonial Virginia. The family name also appears in Virginia’s Fairfax County and City of Fairfax. But the community college does not directly serve those places. Northern Virginia Community College does.

“Today, I don’t know why anyone would want to name a community college after a British lord,” DuBois said. “It just doesn’t make sense.” That school is being renamed Laurel Ridge Community College.

Some Republican lawmakers objected.

“This decision is a direct response to the ‘cancel culture’ movement, which looks to reject people and ideas that do not fit the current politically correct narrative,” U.S. Rep. Bob Good (R) wrote to DuBois in April, urging the state to keep the Lord Fairfax name. “Efforts such as these encourage an endless cycle of renaming institutions, buildings, and cities across the country under the ruse of political wokeness.”

Around the country, community colleges are often named for counties, cities or regions they serve — and some are named for historical figures with controversial legacies.

Henry Ford College, in Dearborn, Mich., honors the pioneering automaker and industrialist also known for promoting antisemitism. Multiple campuses in Alabama honor George C. Wallace and his wife Lurleen B. Wallace, who both served terms as governor during the civil rights movement. George Wallace was a fierce advocate of racial segregation during the 1960s. He later renounced those views.

There are no signs that the Ford and Wallace college names will be changed soon.

In Virginia, community colleges were founded and named in rapid succession in the 1960s and ’70s. Their emergence coincided with a huge expansion of public higher education nationwide after World War II.

Community colleges at a crossroads: Enrollment is plummeting, but political clout is growing

Now, their names are getting a second and even third look. In July 2020 — weeks after Floyd, a Black man, was murderedduring an arrest in Minneapolis — the Virginia state community college board ordered a comprehensive review of college names and campus building names with an eye to diversity, equity and inclusion. Local college boards were empowered to change problematic campus building or classroom names and to recommend college name changes. The state board has final say over college names.

In Clifton Forge, a mountain town west of Lexington, John Rainone has spent the past year wrestling with the legacy of Dabney S. Lancaster. Rainone is president of a community college named for Lancaster, who held many education leadership positions in the 20th century, including a stint in the 1940s as state superintendent of public instruction when schools were segregated.

Initially, Rainone said, the local college board wanted to keep Lancaster’s name. But board members changed their minds after a researcher discovered that Lancaster had been a national officer in the 1920s in a white supremacist organization known as the Anglo-Saxon Clubs of America. “With this new information, we felt like there was no question,” Rainone said.

The state board approved the local recommendation to drop Lancaster’s name.

On Oct. 18, Rainone said, the college plans to unveil its proposal for a new name. There are three finalists: Headwaters Community College, Mountain River Community College and Mountain Gateway Community College.

“This new name, it really will bring us to a new place,” said Rainone, who added that everyone on campus must feel welcome. “Even if one student questions the college’s inclusiveness because of the college’s name, then I feel like we have not done our job to meet that student’s needs.”

In southeastern Virginia, Thomas Nelson Community College was named for a man who was briefly governor during the Revolutionary War and fought the British at Yorktown. He also was immersed in slavery. Stacey Schneider, an associate professor of history at the college, wrote in an analysis of Nelson’s life that he was given 400 enslaved people at the time of his marriage. Records indicate that he enslaved 219 at the time of his death in 1789. One was emancipated through his will, Schneider wrote, while the rest remained in bondage — transferred to Nelson’s relatives or sold to pay his debts.

“Is he the right fit?” Schneider said in a telephone interview. “Does he fit our population at Thomas Nelson Community College?” Federal data show 29 percent of the college’s 6,300 students identify as Black or African American and 48 percent as White. Ultimately, the state approved a local recommendation to switch to a geographic name, Virginia Peninsula.

Among those opposed to the change was Gary O. Hodges, president of the Thomas Nelson Jr. chapter of the Sons of the American Revolution. The college lists the chapter as the sponsor of a $1,000 scholarship for high-achieving students with interest in history. Hodges said a little more than $50,000 has been awarded over the years.

Hodges said the chapter had no comment on Nelson’s ties to slavery. Nelson’s contributions to the founding of the nation, Hodge said, were sufficient reason to support keeping the name. “Are we unhappy? Yes, we are unhappy,” Hodges said. “But things happen we have no control over.”

Debate arose over a school long named Patrick Henry Community College in Martinsville. Local officials said the name should stay, arguing that it was purely geographic, in recognition of the people the school serves in Patrick County and Henry County along the North Carolina border. State officials pushed back.

The result, Patrick & Henry, was described as a compromise. It contains an obvious echo of the 18th century orator without replicating his name exactly.

“The ampersand means inclusion,” said Patrick & Henry President Greg Hodges, no relation to Gary Hodges. “We could not be more thrilled with where we landed.” About 62 percent of the college’s 2,000 students are White and 20 percent Black, according to federal data.

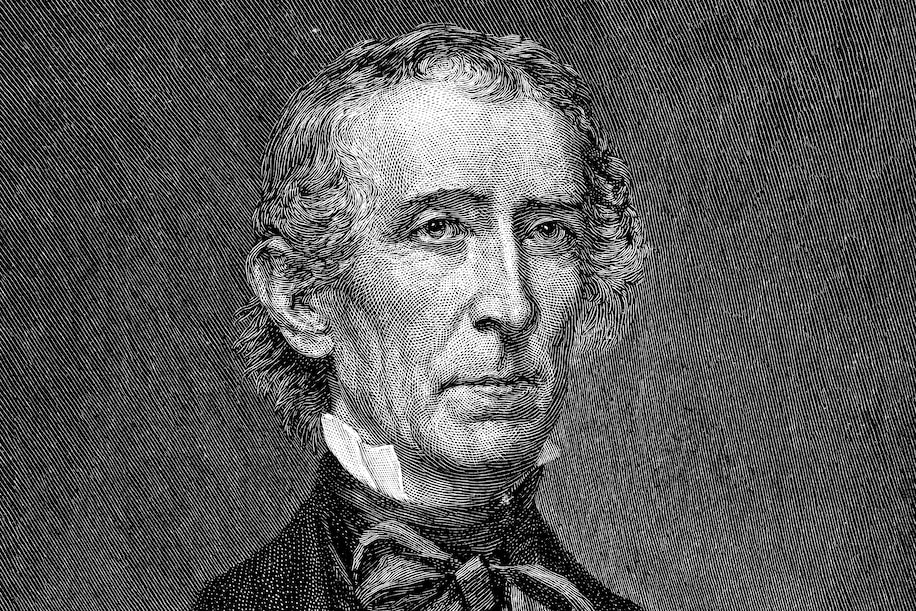

As for John Tyler Community College, officials say there has been relatively little controversy over dropping the name of the 10th president. Tyler, the first to succeed to the presidency after the death of an incumbent, established important historical precedents during his term in the 1840s. But he sided with the Confederacy at the end of his life, winning election to the Confederate Congress, an action many believe was the ultimate betrayal of his country. Tyler was also an enslaver. How his name became attached to a community college founded a century later is unclear.

“I have asked myself that question many times,” said Edward “Ted” Raspiller, the college’s president since 2013. “If you can find why, I would love to read it.” Officials describe the school as “becoming Brightpoint,” with the official switch taking effect next year. The state board approved the new name in July. Raspiller estimated the name change will cost less than $1 million for new signs and other necessities. The new name, which has no geographic connection to the college’s service area, was chosen with help from branding experts.

Brightpoint, Raspiller said, “speaks to the experience we want people to have here. It’s aspirational. We’ve got a pretty bold vision — a success story for every student.” Federal data shows that about 10 percent of the school’s 9,400 students are Latino and 20 percent Black or African American.

Raspiller said he has had little contact with Tyler’s descendants. “We’ve never had a connection with the family,” he said. The Tyler estate, Sherwood Forest, lies about 30 miles east of the Chester campus.

William Tyler, a great-grandson, said in a written statement: “I support the mission of the Virginia Community College System to provide educational opportunities for all individuals, and I believe that by improving lives the VCCS serves the Commonwealth as a whole. To the extent the State Board determines that changing the name of any of the institutions it oversees furthers [the system’s] mission, I support their right to do so.”

Despite the name change in Virginia, John Tyler will still have a connection to another community college. Tyler Junior College, in Texas, is based in a city named for the president.