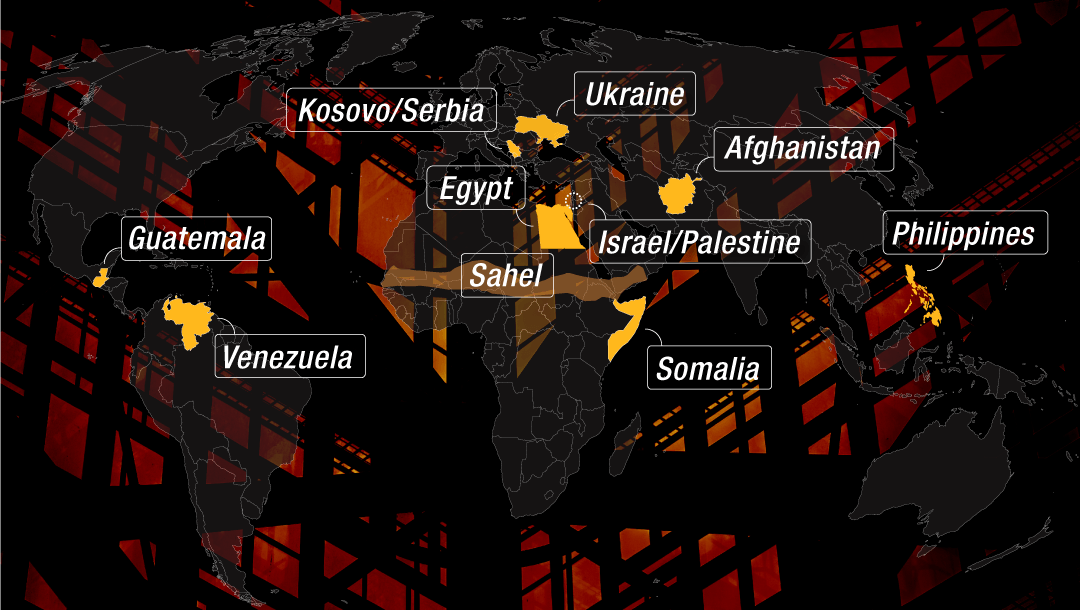

Crisis Group’s Watch List identifies ten countries or regions at risk of deadly conflict or escalation thereof in 2024. In these places, early action, driven or supported by the EU and its member states, could enhance prospects for peace and stability.

President’s Take: Europe Has a Difficult Hand to Play in 2024

One month into 2024, it is hard to look at the global landscape without some foreboding. The headline conflicts of 2023 rage on in Ukraine, Gaza and Sudan; the Middle East is inching ever closer toward regional conflagration; and little suggests that long-running conflicts from the Sahel to Myanmar are anywhere near abating. The coming year also promises change and uncertainty, with national elections in 64 countries, some of which could have enormous geopolitical consequence. Perhaps foremost among these is the election in the United States, where former President Donald Trump – whose transactional “America First” mindset threatens NATO and other longstanding U.S. alliances – is likely to be the Republican nominee taking on Democratic incumbent Joe Biden.

Europeans will also go to the polls to elect members of the European Parliament and, in some cases, national governments, too. Foreign policy rarely drives European elections, which tend to be determined by economic and other domestic issues. But an uptick in conflict and instability is affecting European core interests and the global economy, including key maritime routes. Even if not foremost on voters’ minds, these flashpoints are increasingly dominating headlines in Europe and may well play an outsized role in 2024 polls. As described in the Watch List entries below – as always, a non-exhaustive list of challenges facing the EU and member states – Europe’s next crop of leaders will have a difficult hand to play amid more fraught world affairs.

Surging Conflict amid a Peacemaking Crisis

Nowhere are the challenges clearer than on the EU’s own eastern flank. Two years after its all-out invasion of Ukraine, Moscow still appears bent on the same goals that prompted its aggression, seeking not just swathes of Ukrainian territory but its neighbour’s vassalisation. After Ukraine’s much-anticipated counteroffensive failed to drive Russian troops back over the course of 2023, the parties have hunkered down behind lines that, at least for now, seem frozen, while Russia tries to hobble Ukraine’s infrastructure and break its will through aerial attacks.

Despite the setbacks, Kyiv is determined to fight. The good news is that Ukraine’s Western partners have helped it build up an air defence that so far appears to be holding. The bad news is that U.S. support, which has been crucial in helping Kyiv hold the line against Moscow for nearly two years, could well peter out. In the U.S., Trump is actively working from the campaign trail to undercut congressional support for a new aid package. He has intimated that he would scale back assistance if elected and force a deal between Kyiv and Moscow.

To Europe’s south is the war in Gaza and the growing danger of a wider Middle East confrontation. Following Hamas’s brutal 7 October attacks, Israel has launched a devastating military campaign in the strip, seeking to eradicate the group and in the process rendering much of the territory uninhabitable. The human toll has been staggering, and each day brings a graver risk that the Gaza conflict sparks a full-fledged regional war. Houthi rebels are using Palestinian suffering as a pretext to attack global shipping in the waters surrounding Yemen, disrupting global trade, and sending prices of many goods soaring in Europe. Many capitals around the world question why Western powers, so outspoken about Russian abuses in Ukraine, mute their criticism of the catastrophe in Gaza, undermining the EU’s advocacy for human rights and civilian protection elsewhere.

Meanwhile, new and resurgent conflicts from the Sahel to the Horn of Africa call into question the impact of years of European stabilisation efforts, and highlight what Crisis Group has elsewhere identified as a wider crisis in peacemaking. War is on the rise, with more leaders seeing they can get away with pursuing their ends militarily. Rarely are today’s conflicts ending through negotiated peace deals. Indeed, some – from the civil war in Ethiopia’s Tigray region to the conflict in Afghanistan – wind down only when one party has had its way. Partly this trend owes to geopolitics. Greater friction between the U.S. and China, as well as the breakdown of Russia-West relations, have left multilateral diplomacy on life support. More regional powers have themselves got involved in local wars, often making them harder to resolve.

This new reality is perhaps most vividly illustrated in the civil war tearing apart Sudan. (Although not addressed in depth here, that conflict is the subject of a recent Crisis Group statement.) There, regional powers like Egypt and the United Arab Emirates line up behind the warring parties. Disagreements and wavering focus from the two most powerful mediators, the U.S. and Saudi Arabia, was largely to blame for a long suspension of talks. Meanwhile, largely unchecked by international pressure, the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces are threatening to overwhelm the country’s east – a situation that could lead Sudan to fragment in the same way that Somalia did in the early 1990s.

The Elections Landscape

Alongside the menacing conflict landscape, major elections across the globe could jeopardise parts of the global security architecture. In 2024, for the first time, national elections will take place in countries inhabited by half the planet’s population.

These polls will be spread throughout the year. One potentially consequential vote has already occurred. In Taiwan, the early January victory of Democratic Progressive Party’s Lai Ching-te – who Beijing sees as a separatist – could exacerbate cross-strait tensions and U.S.-China relations. Fortunately, both Washington and Taipei have taken prudent steps to reassure Beijing of their intent to maintain the status quo. As covered in Watch List entries below, in Venezuela, the presidential election due in 2024 offers a chance (if a long shot) at forging a route out of the country’s protracted crisis, while in Somalia, in contrast, state-level and local council elections – due in November – could reignite political and clan tensions amid a delicate security transition. EU policymakers will no doubt also be keeping a keen eye on elections in key regional powers, including Pakistan (8 February), Indonesia (14 February), India (between April and May) and South Africa (between May and August).

European Parliament elections in June will set the bloc’s broad direction for the next five years, [and] offer insight into the EU’s evolving political landscape.

Closer to home, European Parliament elections in June will set the bloc’s broad direction for the next five years, offer insight into the EU’s evolving political landscape, and establish who influences nominations for top EU jobs that will shape the bloc’s future foreign and security policy. Though the centre right is likely to remain the largest bloc, the elections could further manifest a rightward shift of European politics. Current opinion polls predict that the far right could become the third-largest group in the European Parliament with big wins for populist parties such as those led by Viktor Orbán in Hungary and Marine Le Pen in France. Such parties, which could (depending on their showing) have a bigger hand in selecting EU leadership, are diverse, but tend to be Eurosceptic and oppose stronger EU integration, including in foreign, security and defence policy and enlargement. Many are sceptical about aid to Ukraine.

Presidential and parliamentary elections in nine EU member states, including Finland, Portugal, Slovakia, Lithuania, Belgium, Croatia and Austria, should also serve as an indicator of where Europe is headed. Here, too, there is a growing prospect that the far right makes gains and emerges emboldened, particularly in Austria and Portugal.

Looming over all these contests, however, is the U.S. presidential vote, which looks likely to involve a rematch between President Biden and his predecessor Trump. As the effective Republican party leader and its presumptive nominee, Trump already shapes Republican foreign policy debates including over legislation that would impose new immigration restrictions and appropriate funds to assist Ukraine. He also calls into question U.S. support for NATO, willingness to defend Taiwan and commitment to treaty allies in the Asia-Pacific.

The threat Trump poses to the decades-old transatlantic partnership is double-barrelled. First, in the area of peace and security, Trump’s transactional approach, coupled with his view of U.S. allies as free riders, could well augur a series of tense negotiations in which Washington seeks financial and political concessions in return for protection. Some demands may be more than what U.S. allies are prepared to stomach. Even where deals are reached, adversaries may question how committed the U.S. is to standing behind its allies, sensing that its loyalty is for sale. Secondly, in the area of values, Trump’s disdain for democratic norms – he still denies that Biden won the 2020 election, shows open contempt for the judicial processes in which he is ensnared and professes admiration for strongmen like Russian President Vladimir Putin – would pose a perhaps insurmountable obstacle to imperfect but important cooperation in the service of civil and political rights around the world.

European policymakers for now seem likely to hold their breath and hope for a Biden victory. Opinion polls suggest the candidates are closely matched, and Trump, who carries significant legal and political baggage and lost his last contest with Biden, could well lose again. Still, the more prudent course today would entail some forward planning. For example, given that many European leaders see Russian aggression in Ukraine as an existential threat, they should prepare to help Kyiv hold the line, and deter Moscow for the long term, with or without U.S. backing. That implies stepped up defence production and probably also larger militaries. While NATO members have made commitments to this effect, actual investments have lagged.

While the path forward on other issues may be less clear-cut, surging crises and conflict around the world present Europeans a sober reality. The multilateral institutions that for decades have contributed to international peace and security are barely muddling through, while the trans-Atlantic partnership on which Europe security depends does not provide a sufficiently reliable breakwall. Over the coming year, the continent’s leaders will have to consider how to compensate – tailoring their goals to what they can achieve and making investments in their own defence and in conflict resolution and peacemaking that will continue to serve European interests in an ever more dangerous world.

Africa

Reorienting Europe’s Approach in the Sahel

Each of three countries of the central Sahel – Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger – has seen major upheaval in the years since 2021, bringing the region into a new chapter. Army officers in all three have seized power through bloodless coups, alienating France, the states’ chief foreign patron, and forging links among one another to better resist external pressure. These regimes, bent on, as they see it, restoring sovereignty over all their territory and doubling down on operations against jihadist militants that have bedevilled the Sahel in recent decades, are channelling scant resources to military campaigns at the expense of delivering basic public services. In the rural areas where most fighting takes place, residents are increasingly exposed to abuses, whether at the hands of government troops, jihadists or other armed groups. At the same time, the French troops that were battling militants alongside Sahelian armies have departed, as have UN peacekeepers. Wagner Group mercenaries have deployed in Mali, while Russia has reinforced its security ties with the authorities in Niger and Burkina Faso, adding a patina of geopolitical competition to the picture. The European Union, which maintains its relations with the central Sahelian states, has a dilemma: the juntas are far from ideal partners, but they are likely to remain their main interlocutors for the foreseeable future. Europe needs a thorough overhaul of its regional strategy.

To that end, the EU and its member states should:

- Limit security cooperation to keeping military-to-military channels open while urging the Sahel’s new authorities to explore non-military solutions to insecurity, including dialogue with disaffected communities and groups.

- Reorient their policies toward the long term in three domains: 1) strengthening the capacity of governments to provide basic services, notably in education and health; 2) supporting local efforts to create fairer and more equitable societies, particularly for women and politically underrepresented groups; and 3) combating the impact of climate change.

- Press for initiatives to protect vulnerable civilians such as the displaced and those who have suffered the most from deadly violence.

- Consider linking long-term investment with a requirement that partner governments pursue counter-insurgency strategies that show a minimum of respect for human rights.

A Single-Minded Military Approach

The military regimes that seized power in Mali (2021), Burkina Faso (2022) and Niger (2023) have turned their backs on France, the former colonial power which until recently was the driving force of international efforts to fight jihadists in the Sahel. They have also dismissed the multi-dimensional approaches – based on security, development and governance – promoted, at least in principle, by Western partners and the UN. All three have stepped up military operations against jihadists – and, in Mali, against non-jihadist former rebel groups that signed a 2015 peace deal with Bamako. They are courting new security partners, Russia in particular. Egged on by Mali, which contracted with the Wagner Group, a Kremlin-linked outfit, in 2021, Burkina Faso and Niger are now strengthening links to Russia.

Although the departure of Western and UN forces has not brought about the state collapse that some observers had anticipated, the three countries’ new defence policies have yet to translate into security gains. The recapture of Kidal, in northern Mali, from rebels in November 2023 by the Malian army and its Russian backers lent credence to the authorities’ talk that their forces are gaining ground. But insecurity remains rampant across the region. Mass killings occur with alarming frequency in the countryside, with photographs of dead women and children appearing regularly on social media. According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, 2023 was the region’s deadliest year since militants first overran northern Mali in 2012. All the warring parties, including the national armies, have attacked civilians. In Burkina Faso, jihadists have laid siege to several towns, slowly starving residents who are unable to work their fields. The UN refugee agency puts the number of displaced persons at a record 2.7 million, the bulk in Burkina Faso, where jihadists allegedly control over 40 per cent of the territory. Military regimes are not the only ones to blame for this situation, but their determination to wage brutal warfare contributes to worsening violence against civilians.

The new regimes’ single-minded military orientation has cemented ties among the new authorities in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger. In September 2023, the three countries launched the Alliance of Sahel States, partly in response to a threat by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) to reverse the previous month’s coup in Niger. The Alliance was conceived primarily as a mutual defence arrangement, but the officers are already mulling a political and even monetary union. Though ECOWAS is considering softening the sanctions it imposed on Niger after the junta seized power there, animosity toward the regional bloc, which continues to press for a return to constitutional rule in all three countries, remains high.

The EU’s Bind

Despite their hostility toward France, junta leaders thus far have stopped short of openly antagonising the EU itself. They are still open to diplomatic relations with European countries, and they still receive humanitarian and development aid from Western countries, but they are ready to reject this assistance if they dislike the conditions. In Burkina Faso, they have also submitted requests for military equipment such as automatic rifles to the EU. At the same time, the officers are well aware that other foreign powers – Russia in particular but also China, Iran and Türkiye – see opportunities in the Sahel. Their stance toward the EU is hardening as a result. In November 2023, Niger’s generals repealed a law – viewed by the EU as a landmark measure – that had been instrumental in curbing migration to Europe from Africa. The following month, Niamey terminated its security and defence agreements with the EU.

The EU is in a bind. Member states are discussing where to go from here, including at an EU foreign ministers’ meeting coming up on 19 February. Paris hopes to isolate the new regimes until they become more conciliatory with their former allies and agree to reinstate some form of democratic rule. France’s ouster from the central Sahel has deprived European security cooperation there of its centre of gravity. EU states, divided over how to deal with the new circumstances, may now see the mechanisms through which the bloc has channelled its money and efforts dismantled. One such mechanism is the G5 Sahel, a coalition of five Sahelian countries that was to enhance border patrols and coordinate development policies. After Burkina Faso and Niger pulled out in late 2023 – Mali had already quit the previous year – remaining members Chad and Mauritania suggested they would accept the alliance’s dissolution.

Looking ahead, the EU will struggle to compete with security partners like Wagner, Russia and even Türkiye.

Looking ahead, the EU will struggle to compete with security partners like Wagner, Russia and even Türkiye, whose industries supply arms that Sahelian capitals deem suited to their needs and means. The EU has sought to adapt its security offer, notably through the European Peace Facility, which provides military equipment, among other things. Niger was to be the first Sahelian country to benefit from this instrument until the coup halted these discussions. The EU’s military missions on the ground have also lost their purpose. The EU has suspended its training mission in Mali given Russia’s growing presence. After the coup in Niamey, the EU likewise placed the Military Partnership Mission Niger on hold, and later in the year the new authorities withdrew consent for its deployment, thus putting an end to it.

France aside, almost all EU member states want to stay engaged diplomatically in the central Sahel. But their strategy for the Sahel, defined in the previous decade, is no longer appropriate, and they are struggling to adjust it to changed circumstances. Most members states are ready to engage with imperfect democracies, and even with leaders drawing closer to Moscow, but they have a red line: they refuse to support regimes if they prove too repressive and commit massacres. Some EU member states, are leaning toward drastically scaling back ties with Sahelian regimes, partly because the conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East are higher priorities. Others want to continue supporting civil society and spending on development and humanitarian aid as part of efforts to curb irregular migration to Europe. Still others want to jostle with the new non-Western security partners for influence in the region. They advocate maintaining state-to-state links, including in the security field, even if they want to define red lines such as violence against civilians or deals with Wagner.

Redrawing the EU’s Policy Lines in the Sahel

In her State of the Union speech in September 2023, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen floated a plan to work with EU High Representative Josep Borrell on a new European strategic approach for Africa, which would focus on cooperation with legitimate governments and regional organisations. But in the Sahel, this call comes at a time when the EU seems to be losing momentum in attempts to affect regional developments. Although in a difficult situation, the EU is not condemned to play a marginal role watching the region further plunging into chaos. An in-depth review of its Sahel strategy could set a new course, restore coherence to its actions and regain its dwindling influence in the central Sahel.

All this requires that member states set aside, as best possible, their differences on their approach to the new authorities in the Sahel. Each member state is entitled to articulate its own priorities. But the EU remains a forum in which member states can and should make compromises to preserve their common interests, notably that of a strategic union that offers an attractive governance model and is a credible partner in the eyes of the world. To this end, member states must agree to a common, pragmatic course in the Sahel. France is going through a difficult ordeal in the region. Paris is right to take the time to reconsider the ties it wants to maintain with Sahelian states. At the same time, it should not stand in the way of European member states willing to maintain Europe’s commitment to the central Sahel, which would be better for France than opening even more space for its most serious rivals to consolidate their influence in the region. As the EU is recalibrating its policy in the Sahel, the EU should therefore consider an approach along the following lines:

First, the EU should tamp down its security focus, which has been front and centre of previous policies aimed at combating jihadist groups and stemming migration. Conditions no longer allow for cooperation with military regimes, given their partnerships with Wagner that are incompatible with EU norms and/or given the conduct of military operations that are turning increasingly abusive toward their own citizens. Security cooperation remains possible, but ambitions should be limited to promoting military-to-military contacts and pressing the governments to protect civilians and explore non-military solutions to insecurity, including through dialogue with disaffected communities and groups.

The EU should develop a new narrative for its regional ambitions by shifting its focus from immediate security issues to structural causes of Sahelian crises.

Secondly, and more importantly, the EU should develop a new narrative for its regional ambitions by shifting its focus from immediate security issues to structural causes of Sahelian crises. One task is to combat the effects of climate change, which has had a particularly severe impact on the region and fuelled in subtle ways violent competition over resources. Another is to strengthen governments’ capacity to respond to the needs of populations that are among the world’s youngest, but also poorest, especially in education and health. The EU has long invested in these domains, but in recent years, its actions had been too tightly subordinated to consolidating immediate security gains in vulnerable regions with very limited and often unsustainable impact. Improving governance and delivery of public services requires a longer-term approach. Lastly, the EU should support efforts of vulnerable civil society groups striving to create fairer and more equitable societies, particularly for women and politically repressed groups.

Reorienting the EU’s action toward these long-term issues must, however, surmount several major challenges. Investing in long-term issues is hard enough, but doing so with governments less inclined to cooperate with the EU makes it even harder. There is no easy answer to this conundrum, but the Union has tools at its disposal. The EU and its member states should maintain their diplomatic and operational ties with the Sahelian governments and remind them that nationalist rhetoric and security-oriented policies are insufficient to stabilise states. Europeans especially need to urge Sahelian authorities to improve basic service delivery (something the EU had rightly identified as one of the root causes of conflict in the past) and offer continued funding for these efforts. But they should do so in a more transactional fashion, linking EU long-term investment to an obligation for partner states to ensure that counter-insurgency policies comply with a minimum of respect for fundamental human rights. Since the EU retains an undeniable advantage over the Sahelian states’ authorities, whose finances are limited, it should use this leverage to work toward ending the spiral of deadly violence the populations suffer from, including at the hands of government actors.

“The Sahel is a test for the EU”, High Representative Borrell declared in September 2023, referring to the need for member states to restore the community’s solidarity and capacity for joint action. The region is also – perhaps above all – testing the EU’s ability to strike a better balance between short-term approach of security with longer-term policies adapted to structural challenges.

Somalia: Making the Most of the EU-Somalia Joint Roadmap

The Somali government has a crucial year ahead in 2024. Its offensive against Al-Shabaab, the Islamist insurgency besetting the country since 2007, has sputtered since making important gains in the second half of 2022. The government promises to “eliminate” the group by year’s end, but the goal seems beyond reach. For one thing, Mogadishu will likely soon have less help: the AU Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS) that augments its campaign is to wind down in December, and discussions about a multilateral follow-on force are just getting started. The prospect of state-level elections has already reignited political and clan tensions. Additionally, as part of its plan to complete a provisional constitution, the government seeks wide-ranging changes to the electoral code ahead of national elections slated for 2026. Opposition groups eye these reforms warily, arguing that the government aims to use them to retain power.

The state also faces other old and new challenges. The humanitarian situation remains precarious, with climate stresses adding to the burden placed on long-suffering Somalis by the country’s decades-long conflicts. Meanwhile, an unexpected new crisis arose at the new year, when neighbouring Ethiopia said it had agreed with Somaliland – whose 1991 proclamation of independence Mogadishu rejects – to lease a parcel of land on the Gulf of Aden.

The EU and its member states can help address Somalia’s challenges by:

- Remaining engaged in discussions about forming a new AU-led multilateral mission to succeed ATMIS and detailing the conditions under which they could provide funding in the absence of other sources, even as Brussels increases its support for building the capacity of Somali forces;

- Urging the Somali government to undertake broader reconciliation efforts including by focusing on grassroots convenings within a framework that can endure from one administration to the next;

- Pressing Mogadishu for a long-term approach to tackling Al-Shabaab that goes beyond military measures. To this end, they should indicate their support for exploring the prospect of eventual dialogue with the insurgents;

- Working to contain tensions related to the Ethiopia-Somaliland agreement, including by facilitating back-channel diplomacy between Addis Ababa and Mogadishu;

- Making clear the importance of Mogadishu sticking to the EU-Somalia Joint Operational Roadmap adopted in May 2023. Depending on how the security situation evolves, Brussels could reward progress with additional (technical, financial and other) support or reduce assistance if progress stalls.

A Struggling War Effort amid Other Challenges

As 2024 approached, Somalia was on a streak of big wins on the international stage. In the last quarter of 2023, Mogadishu persuaded the UN Security Council to lift an arms embargo that had been in place since 1992. The country completed a debt relief program backed by the International Monetary Fund, reducing its external debt from 64 per cent of GDP at the end of 2018 to about 6 per cent at the start of 2024. The East African Community admitted Somalia as its eighth member, marking the start of an integration process aimed at reducing economic barriers and deepening trade opportunities, including eventual visa-free travel.

Then, on 1 January, came a thunderbolt. Addis Ababa announced that it had struck a deal with neighbouring Somaliland to give landlocked Ethiopia access to a 20km stretch of coastline, reportedly to establish a naval facility. The revelation rattled Mogadishu – which views itself and not Hargeisa as sovereign in Somaliland and by all appearances was not included in the negotiations – and set off a furor among Somalis who saw it as an insult to national dignity. The degree of popular discontent is likely to mean that President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud’s administration will spend precious time in 2024 addressing the fallout.

But President Mohamud, who took office after a protracted electoral process in May 2022, will nonetheless need to dedicate significant effort to handling domestic priorities. There, the picture is decidedly gloomier than in foreign policy. The offensive against Al-Shabaab has tapered off after initial advances, which loosened the insurgents’ grip on swathes of central Somalia. A key element of the government’s strategy was to tap into clan resentment of the group, and partner with macawisley, or clan militias, to take the war to Al-Shabaab’s rural strongholds. By early 2023, however, Al-Shabaab had adjusted, turning to guerrilla tactics. Its fighters withdrew from population centres, returning later to attack over-exposed government forces. Mogadishu had difficulty supplying the front, and its new recruits lack battle experience. At the same time, Al-Shabaab reached out to clans to dissuade them from allying with the government.

Thus, a campaign Mogadishu billed as striking a death blow to the insurgency is now largely stalled. The Somali government has managed to hold most ground it seized, but in areas such as southern Galmudug, Al-Shabaab has pushed it back. Even in towns and villages authorities recovered from the insurgency, the government is struggling to consolidate its gains. Stabilisation efforts to provide basic services and oversee reconciliation dialogue have been slow. The overstretched authorities have also been unable to deploy enough police and local military-police known as Darwish to provide security. Nonetheless, the government says it hopes to clear the remainder of central Somalia before turning its attention to a second phase of the offensive in the south. Given the problems to date, uprooting Al-Shabaab from its heartlands in the south will be a formidable task indeed.

A major challenge is that the international forces who have been battling Al-Shabaab … are packing up just as Somalia is ramping up its campaign.

A major challenge is that the international forces who have been battling Al-Shabaab alongside the national army are packing up just as Somalia is ramping up its campaign. ATMIS is scheduled to send home the remainder of its 14,000-odd forces by the end of 2024 (two phases of the drawdown have already occurred). Yet few expect Somali forces to be ready to take over from the mission – which plays a big role in holding urban areas and thus freeing the army to stage offensives – when it departs. The government, bullish at first about its capacity to fill the gap the mission will leave, now admits that the timeline is ambitious. At a December 2023 conference, it proposed that the African Union (AU) lead a successor to ATMIS, focused on securing key towns and infrastructure as well as giving air and ground logistical support to local forces.

The conversation about a follow-on mission is embryonic, however. The Somali plan provides a framework for discussion, but many details, including the force’s size, composition and duration, still need to be worked out. A key missing piece relates to funding. ATMIS and its predecessor the African Union Mission in Somalia relied heavily on the EU, which paid the troops’ stipends. Yet the EU has long sought to reduce its financial contribution. It is reluctant to be on the hook again for a follow-on mission – although differences of opinion exist among member states.

The hesitancy about open-ended subventions owes to several factors. First, some in the EU feel its funding, much of which flows to the troop-contributing countries for the stipends, has supported only a short-term solution when the main task is to build up Somali forces. Secondly, although ATMIS has deferred to Somali forces for the conduct of offensive operations, some member states complain that it should engage in more combat itself. They view ATMIS as expensive, given its limited role, though it is cheaper than a typical UN peacekeeping operation. Thirdly, some in Brussels resent the lack of burden sharing, especially as other international partners present in Somalia grouse about adverse ramifications whenever the EU wishes to trim its contributions but offer few options of their own.

The search for alternative sources of funding for a follow-on mission remains arduous. The UN and AU struck a framework agreement in late 2023, by which the global body is to fund up to 75 per cent of certain AU-led peace operations. Political will exists in Mogadishu, as well as at UN and AU headquarters, to test this approach for a follow-on mission in Somalia, according to diplomats, although much work lies ahead at the technical level to align AU troop management procedures with those of the UN. The AU and Somali government have also looked to non-traditional donors – such as China, Gulf states and Türkiye – to fill the gaps, but none have stepped up to the plate.

Tensions related to competition for power and resources among Somali elites continue to foment instability.

Tackling Al-Shabaab is only part of the equation in bringing peace to Somalia, however. Deep-seated tensions related to competition for power and resources among Somali elites continue to foment instability. Such divisions, at the national level between the federal government and federal member states, and within the states themselves, are rooted in longstanding grievances, underpinned by the lack of a comprehensive political settlement in the country. They often fuel conflict in the run-up to elections, which many view as manipulated to favour incumbents.

The next round of state-level elections threatens to restart this dynamic. Due in November, these will be held concurrently for the first time, in a bid to align the timetables (aside from semi-autonomous Puntland in the north, which staged its vote in line with its previous electoral calendar in early January). The modality for the elections, ranging from the persistent but unachieved goal of universal suffrage to the more familiar (and thus realistic) indirect model of clan delegates picking winners, remains unclear. Political tensions in many member states are mounting, amid complaints that the elections have already been delayed several times. If these votes are not handled in an open, inclusive and transparent manner, or if Mogadishu tries to intervene in state-level affairs by backing candidates, the tensions could further fracture some member states.

Splits over the next elections at the national level are also zooming into view. President Mohamud seeks to push through parliament an electoral model that adopts universal suffrage in 2026, including with a direct vote for the presidency. This change would in effect shift Somalia away from a parliamentary system of governance. The proposal would also limit the playing field to two political parties, ostensibly to discourage formation of clan-based parties. These ideas are already facing significant pushback in parliament and among the political opposition.

The relationship between the federal government and federal member states has improved under Mohamud, but it remains a work in progress. Mohamud convenes the National Consultative Council for regular, though still ad hoc, meetings between federal and member state leaders. But member state Puntland, accusing Mogadishu of seeking to concentrate power, has boycotted the Council for the past year, putting it under a cloud. The conclusion of Puntland’s elections, which took place in early January, provides an opening for the two sides to turn the page, even though the incumbent retained power.

Finally, the humanitarian situation in Somalia remains dire, with vulnerable groups, including women, bearing the brunt of it. While 2024 might not bring the severe shocks of previous years – including five consecutive failed rainy seasons followed by excessive rainfall and flooding amid an El-Nino-influenced rainy season in late 2023 – the compound effect of previous crises remains while climate change gathers speed.

What the EU and Its Member States Can Do

The EU has consistently been one of Somalia’s major partners. Brussels has invested €4.3 billion in the country since 2007, focusing on security. This amount includes the aforementioned troop stipends for ATMIS and its predecessor, to the tune of €2.6 billion in that period. Relations between Brussels and Mogadishu have warmed since Mohamud returned to the presidency in May 2022 (he previously held the office between 2012 and 2017), after a chill during the tenure of Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed “Farmajo” (2017-2022). The EU was notably one of the first outside actors to issue a statement calling for respect of Somalia’s territorial sovereignty following the Ethiopia-Somaliland port access announcement.

A roadmap the EU and Somalia adopted in May 2023 provides a framework for the EU-Somalia partnership through 2025. At its core, it brings the various EU instruments and member states under a single framework with the Somali government to detail joint priorities. The roadmap outlines three areas of partnership: inclusive politics and democratisation; security and stabilisation; and socio-economic development. Completing the transition from ATMIS to Somali security forces by December is one of the listed milestones.

The joint roadmap will have little chance of success if the security situation in Somalia deteriorates precipitously. It will thus be important for international forces to be in Somalia past 2024, in line with the Somali government’s new request. If the UN assessed contributions, the prospect of which is uncertain, do not come to pass, continued EU financing will likely be required. Despite understandable fatigue in Brussels after a decade and a half of support, the EU should prepare itself for a contingency plan by coming to a common position on the issue of continued funding as soon as practicable. The EU should make clear under what conditions it could offer aid to a new mission, such as the level of cost sharing it would want to see from others or the components of the mission it would be comfortable funding. Doing so earlier rather than later would provide a degree of clarity while other sources of financing, in particular from the UN, are explored.

The EU can also help plug holes in the Somali security sector and address concerns that too much of its support goes to non-Somali troops. Channelling additional funds via the European Peace Facility could help improve Somali forces, particularly in equipment, logistics and training. The European Union Training Mission could consider how it can provide more mentoring for the soldiers it trains. The European Union Capacity Building Mission could also enhance its training programs for police, and even extend them to Darwish (state-level military police) personnel, to help Somali authorities hold areas vacated by Al-Shabaab but where the army lacks the personnel to leave garrisons.

The EU should press the Somali government to consider initiating a comprehensive reconciliation project that … moves beyond narrow, elite-driven politics.

Brussels should also support steps to address the national and local-level grievances and disputes that undergird conflict in Somalia. The EU should press the Somali government to consider initiating a comprehensive reconciliation project that both moves beyond narrow, elite-driven politics and endures from one presidential administration to the next. A component would be grassroots conferences to discuss local expectations of how governance should function in Somalia, including in areas recovered from Al-Shabaab. Participants should be representative of local populations, including women and other vulnerable groups. This bottom-up approach has the most promise as a method to durably support finalising the provisional constitution. Closed-door consultations among rivalrous politicians are unlikely to yield a compact with broad buy-in.

The EU should also support a long-term approach to fighting Al-Shabaab, shifting from the short-term objectives President Mohamud has pursued to date. The government’s military-first approach is understandable, but most in Somalia and beyond understand that, as Crisis Group and others have argued, Al-Shabaab will not be defeated by military means alone. The EU should press Mogadishu to focus more on stabilisation in recovered areas to prove that it can govern them better than Al-Shabaab. The EU should also privately signal it would back a federal effort to consider dialogue with the insurgency, if Mogadishu decides to pursue that path.

The EU can also help tamp down acrimony resulting from the Ethiopian agreement with Somaliland, continuing the proactive stance it has taken through its collective institutions to date. Its actions have included discussions between President Mohamud and EU High Representative Josep Borrell and regional engagement by the EU’s special envoy to the Horn of Africa, Annette Weber. The deal has inflamed tensions at a delicate time in the Horn. While the risk of immediate conflict is low and Mohamud is treading a fine line to address the issue diplomatically, the EU can use its ties with Addis Ababa, Hargeisa and Mogadishu to promote back-channel discussions aimed at lowering the volume.

Finally, Brussels should make sure to follow up on implementation of the joint roadmap. On top of regular assessments of progress, it could make adjustments in the absence thereof, which in turn could include evaluating the level of technical or financial support it reserves for Somalia. Whether to go down this route will of course have to be evaluated in light of prevailing circumstances, including with respect to the security situation. But too often in Somalia, new administrations offer lofty promises but succumb to inertia and political infighting with an eye to the next election. The Somali-EU roadmap provides a framework for keeping matters on track, and 2024 will offer an important opportunity to test the approach.

Asia

Toward a Self-sufficient Afghanistan

Afghanistan sank deeper into isolation in 2023 as Western donors slashed aid budgets, partly in revulsion at the Taliban regime’s oppression of women and girls, while maintaining sanctions and other forms of economic pressure. The country’s biggest trading partner, Pakistan, put up commercial barriers as Islamabad turned against its former Taliban protégés in a dispute over anti-Pakistan militants becoming more violent in the borderlands. It also joined Iran in kicking out hundreds of thousands of Afghan refugees, sending them back to impoverished Afghanistan. Left with little help, the Taliban pushed ahead with self-financed infrastructure projects, took stern anti-corruption measures, stabilised the national currency and enhanced customs revenues. Along with what foreign assistance remains, these policies staved off economic disaster and mitigated the country’s humanitarian crisis, but the tenuous equilibrium is unlikely to hold much longer. The most vulnerable groups, especially women and girls, face serious risks on account of much of the outside world refusing to engage with the Taliban government. The Taliban bear most of the blame for their pariah status, having rebuffed foreign entreaties to ease their draconian restrictions on the rights of girls and women. But the regime in Kabul seems unlikely to give in to these demands in exchange for more aid, let alone to collapse under the weight of outside opprobrium. Meanwhile, the poorest Afghans are the ones shouldering the burdens imposed by the West as donors shy away from supporting the steps necessary for Afghanistan to become self-sufficient.

The European Union and its member states can help address these urgent challenges by:

- Reversing aid cuts. In 2023, European donors sent Afghanistan half the humanitarian assistance they had given in 2022, forcing aid organisations to drastically cut down the number of beneficiaries. The EU and its member states should up their support for the 2024 UN appeal to help the country recover from war, drought, floods and earthquakes and cope with the mass repatriation of Afghans by neighbouring countries.

- Answering the call in the UN’s independent review, released in late 2023, for more international cooperation with the Taliban. Mandated by the UN Security Council, the study concluded that maintaining the status quo will likely have “dire consequences”. The EU should heed the warning, pivoting from short-term aid to long-term development assistance; rehabilitating the central bank; and helping Afghanistan restore regular transit and trade with the world.

- Providing assistance to Afghan women and girls more effectively and sustainably. Though it may seem counterintuitive, the most principled response to the Taliban’s discriminatory policies, which deprive women and girls of many basic rights, is to work with the regime – at least to some extent and with considerable caution – as the government remains the most efficient, most durable means of delivering services to the largest number of Afghans. Many cannot be reached any other way.

- Opening doors to the most vulnerable Afghans for safe emigration. EU states agreed on common procedures for screening asylum seekers in 2023; these should now be extended to address the claims of the people most at risk inside Afghanistan – women, ethnic minorities and dissidents – before they undertake the dangerous journey to Europe.

Deeper Isolation, More Fragility

More than two years after the Taliban swept back to power, Afghanistan remains mired in a humanitarian disaster. In October 2023, the UN estimated that 13.1 million Afghans, or 29 per cent of the population, were facing high levels of food insecurity. That represents an improvement from a year earlier (41 per cent) but the situation remains dire – especially for women and girls, who often suffer the worst effects of hunger. With overlapping crises on the horizon, the UN predicts that the proportion of Afghans falling into the worst categories of food deprivation will rise to 36 per cent in the coming year.

On the other hand, the country has not been so peaceful for decades. The Taliban have established greater control over the country than anyone has managed since the late 1970s. Violence subsided over the last two years as the Taliban suppressed small insurgencies: the local branch of the Islamic State, whose attacks occurred mostly in the eastern provinces; and anti-Taliban political factions concentrated in the north. The improved security allows aid workers to travel farther afield than ever before and trade to flow more smoothly. Parents also report fewer safety concerns about sending children to school. Enrolments climbed – overall (and for girls, despite the bans on secondary education, as the proportion of Afghan girls in primary classes increased from 36 to 60 per cent).

Yet the downsides of the Taliban’s strict regime are readily apparent. The new authorities refuse to revisit the bans they imposed in 2022 on girls attending high school and university, leaving girls who wish to continue their studies beyond primary school with few options to do so. Nor do the Taliban seem open to discussing their schooling bans and other regressive policies with international envoys, despite a series of overtures by UN officials and foreign diplomats.

The Taliban have little prospect of taking Afghanistan’s seat at the UN any time soon.

The Taliban’s refusal to compromise has blocked, at least for now, the most promising avenues toward breaking the isolation that has hobbled Afghanistan’s post-war recovery. Partly due to their own intransigence, the Taliban remain under sanctions, the state’s foreign reserves are frozen in overseas accounts and Afghan businesses have trouble making transactions with counterparts abroad. The Taliban have little prospect of taking Afghanistan’s seat at the UN any time soon.

Cut off from global financial systems, the Taliban have still managed to pay civil servants, cover the costs of imported electricity and scrape together funds for rudimentary work on dams, canals and other infrastructure. The regime has cleaned up corruption at customs points, resulting in higher overall revenues than under previous governments. Much of the growth, however, depended on coal exports to Pakistan, which fell off in the second half of 2023 as tensionsgrew along the disputed border.

Islamabad accuses Kabul of harbouring the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), also known as the Pakistani Taliban, a militant group that swears allegiance to the Taliban. The Taliban deny hosting Pakistan’s enemies, but the growing pace of TTP attacks close to the border triggered increasingly sharp protests from Islamabad. Pakistan’s campaign to spur the Taliban to tougher action against the TTP escalated in November 2023, when Islamabad started carrying out mass deportation of Afghans to put further pressure on Kabul. Hundreds of thousands of people have been forced into Afghanistan, many of them homeless and destitute. The Taliban responded by arresting dozens of suspected TTP militants, but by themselves such gestures are unlikely to appease Islamabad, especially if the number of TTP attacks keeps rising.

The humanitarian crisis sparked by large numbers of returnees represented the latest challenge in meeting the basic needs of Afghans in 2023. Pakistan is not the only country pushing out Afghans; Iran also expelled more than 600,000 people in 2023. Stagnant economic growth already spelled trouble for a fast-growing population, with an estimated 500,000 new job seekers annually, but the sudden influx of returnees, many of whom have been abroad for years, will make matters worse. Agriculture, the country’s largest source of employment, has suffered from spells of drought and floods that have worsened in recent years as a result of climate change. Farmers also lost income after the Taliban banned the cultivation of plants used to make narcotics, particularly opium poppy, without providing alternative employment for rural labourers. Thousands of people were displaced by recent earthquakes.

A Roadmap to Stability

At $3 billion, the 2024 UN humanitarian plan for Afghanistan is among the largest in the world, surpassed only by those for Syria ($4.4 billion) and Ukraine ($3.1 billion). Judging by the trends in 2023, however, pledges for Afghanistan seem likely to be disappointing in the coming year. Faced with competing priorities in allocating funds (Ukraine, Gaza) and frustrated by the Taliban’s intransigence on girls’ and women’s rights, European donors, in particular, have been pulling back from the country, giving about half as much ($457 million) bilateral and multilateral humanitarian aid in 2023 as in the previous year ($975 million). Aid workers in Kabul complain that donors seek leverage over the Taliban by withholding assistance, contravening the humanitarian principle that aid not be held hostage to political considerations. The EU and its member states should generously contribute to the 2024 UN appeal for emergency aid and, in the long term, shift to different funding mechanisms to wean the country off humanitarian aid, which by definition is not a solution to the country’s crisis. Greater stability in Afghanistan would serve European security interests, as the vast human suffering in the country today increases the risks of militancy and mass economic migration.

A roadmap to Afghan self-sufficiency exists, but it needs better backing from European states and other major donors. In November, the UN Security Council received the much-anticipated report on international engagement with Afghanistan requested via Resolution 2679 (2023). Led by Special Coordinator Feridun Sinirlioğlu, a former Turkish foreign minister, the review assessed international engagement with Afghanistan and offered practical ways of breaking the impasse with the Taliban. The Council welcomed the report in December and encouraged all concerned to consider its ideas. The coming months will be crucial for getting these adopted.

[UN Special Coordinator Feridun] Sinirlioğlu also recommends that more embassies in Kabul reopen, gradually resuming diplomatic engagement.

The Taliban are sceptical of the report’s proposed path toward legitimacy inasmuch as it requires them to accept international norms on such things as the rights of women and minorities. Still, the report sets out pragmatic steps that European and other international actors should take – even if negotiations on the above issues with the Taliban remain moribund – for the sake of millions of lives and livelihoods in the country. This tack would not entail recognising the Taliban government. But it would mean easing restrictions on development and technical assistance to Taliban-controlled state institutions on topics such as public health; demining; counter-terrorism and security cooperation; agriculture and water management; and adaptation to climate change. The report also calls for restoring international financing for infrastructure projects started before 2021, and now nearly finished, and suggests that outside powers support rehabilitating Afghanistan’s central bank. Sinirlioğlu also recommends that more embassies in Kabul reopen, gradually resuming diplomatic engagement.

The European Union hosted consultations for the UN review, and EU institutions are leaders among donors in several ways raised in the report: for example, the EU maintains a well-regarded diplomatic mission in Kabul even as most other Western embassies remain shuttered. As the report concludes, however, much more work is necessary to restore basic connections between Afghanistan and the outside world – and it should go on regardless of the political differences that are likely to persist between Kabul and foreign capitals. Afghans must be allowed to feed themselves, rather than depending on a dwindling supply of aid.

Helping the country achieve self-sufficiency will help Afghan women and girls. Some European donors, as part of a “principled approach” that EU member states reaffirmed in March 2023, are trimming aid to send a message to the regime that its discriminatory policies are unacceptable. But though such gestures often reflect sincere beliefs among policymakers, they are counterproductive. First, the aid cuts worsen the humanitarian crisis, and plenty of empirical evidence shows that women and girls are disproportionately harmed in such emergencies, a pattern that is only more apparent in Afghanistan. Secondly, isolating the regime to protest its discriminatory policies has no coercive effect on the Taliban; on the contrary, their supporters seem thrilled that the regime is holding firm against the Western states that invaded their country. Finally, enshrining as the first “principle” that the Taliban get not a single euro means handcuffing the aid workers and development professionals whose own principles tend to put higher value on human life and avoiding poverty and disease.

European donors should offer more effective and sustainable development assistance that would better the lives of all Afghans, including women and girls.

Along with statements backing gender equality, European donors should offer more effective and sustainable development assistance that would better the lives of all Afghans, including women and girls. Doing so inevitably requires working with the de facto authorities to some extent. For example, the Ministry of Education remains the only entity offering girls’ primary education at a large scale, even as the Taliban bar girls from higher levels of schooling. Nor is there any way of circumventing the Afghan state to provide electricity, which is essential for (among other things) online classes for girls and women. Similarly, water infrastructure cannot be built and maintained without the state – and such projects are desperately needed, not least by Afghan women whose main employment outside the home is agricultural.

Even with the best aid policy, however, Afghanistan will remain a major source of asylum seekers in Europe. First-time applicants for asylum in the EU are most commonly Syrians (15 per cent) but Afghans have been the second-biggest group for several years, accounting for almost 13 per cent of seekers in 2022. Alternatives are required to the existing informal system in which 3,000 to 5,000Afghans cross into Iran each day, many of them trying to reach Europe on expensive and hazardous migrant trails, and file their applications only after having arrived on European shores. The status quo disadvantages Afghan women, who are less likely to risk the journey despite guidance from the EU Agency for Asylum that women fleeing the Taliban’s oppression should be eligible for refugee status. A useful precedent emerged in 2023 from the Council of the European Union’s conclusions on Afghanistan, in which the EU pledged to use its on-the-ground presence in Afghanistan to help with the “free and safe passage for Afghans who could be received by EU Member States”. Fulfilling this commitment should mean that vulnerable Afghans can apply for EU asylum from inside of Afghanistan, without undertaking the perilous overland journey to Europe. Such procedures would be a safer, more effective way to shelter the Afghans who are worst affected by Taliban rule, including women, ethnic minorities and dissidents.

The Philippines: Keeping the Bangsamoro Peace Process on Track

The peace process in the Bangsamoro, the Muslim-majority region in Mindanao, the Philippines’ second largest island, stands at a critical juncture. Just over a year remains until parliamentary elections take place, which will conclude the political transition under way in the region after decades of war between Manila and Moro separatist rebels. In 2014, the government reached an accord with the main rebel group, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), providing for creation of an autonomous regional authority in the Bangsamoro, which was duly set up in 2019. This accord remains one of the few examples of a negotiated peace anywhere in the world over the last ten years, thanks partly to robust support from the European Union.

Although the peace process has made impressive progress, time is running out for completion of the roadmap set out by the 2014 agreement, which is due to conclude with elections for a permanent regional authority in 2025. Implementation of important provisions, including on disarmament and socio-economic development, is behind schedule. Conflict is surging, in the form of feuds among clans and political rivals, but also rebel infighting, particularly in central Mindanao. Although confined to pockets of the island, the recurrent skirmishes cast a shadow over the delicate transition. Jihadist groups that oppose the MILF, although weaker than in the past, could exploit the volatility. Together, these sources of tension could throw the process off track.

To preserve the peace process’s gains and support development in the Bangsamoro, the EU and its member states should:

- Engage in visible, persistent diplomacy with all parties to press for follow-through on the 2014 accord’s provisions, with public visits to the Bangsamoro’s de facto capital, EU project sites and MILF camps to underscore the bloc’s deep interest in seeing the peace plan to fruition and build confidence in the process among the people most affected. Messages to Manila should stress the importance of meeting financial commitments under the plan, especially with respect to compensating demobilised combatants.

- Continue funding the Third Party Monitoring Team, which has a mandate to review and assess the peace agreement’s progress.

- Explore the possibility of additional funding and other support for socio-economic development in the camps where ex-MILF fighters live, as well as peacebuilding initiatives in Mindanao. More assistance should also be considered for existing programs that can help the interim government address local conflict drivers, such as land ownership. The EU should also stand ready to respond with emergency funds if security deteriorates leading up to the 2025 polls.

- Support local civil society groups working on community peacebuilding and reconciliation as well as women-led organisations, especially in areas, like those in central Mindanao, still suffering high levels of violence.

The Legacy of Internal Conflict

The war between the government and the MILF formally ended in 2014 when the parties signed the historic Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro. Five years later, as agreed, the ex-rebels took power over the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, through an appointed interim authority whose term was meant to be three years but was extended to six on account of the COVID-19 pandemic. Since then, the peace has broadly held. Despite occasional violations, the ceasefire between Manila and the MILF remains in place, and since his election in 2022, President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. and his cabinet have repeatedly committed to honouring the agreement in full.

In the meantime, the Bangsamoro Transition Authority has crafted key legislation, enacting five of seven priority laws foreseen by the peace agreement, and made strides in setting up a new bureaucracy. The peace deal also proved a landmark in terms of women’s participation. Not only did a woman lead the government negotiating panel during the talks, but women have played an active if not equal role in the political transition as a whole: they make up a fifth of the Bangsamoro interim parliament and occupy key administrative positions, including attorney general, a deputy parliament speaker, and heads of the interior and local government and social services and development ministries.

But several interconnected trends are putting the peace process under intense pressure. To begin with, violence has resurged in parts of the Bangsamoro. Local politics remain bloody, with shootings marring the two municipal and village elections that have taken place in the region since 2022. Clan feuds, in particular, continue to roil central Mindanao, causing casualties, displacement and property damage. Many of these disputes stem from the contest for power and resources between ex-rebels and local politicians, some of whom command private militias. Other squabbles have erupted between MILF commanders. Lastly, jihadist groups, which reject the 2014 agreement, while seriously weakened by intensified military operations in recent years, still pose a threat. On 3 December, ISIS-inspired militants set off a bomb during a church service in the town of Marawi, killing four congregants and wounding over 40 more.

While the Bangsamoro has long seen political tensions, polarisation is on the rise and could take an ugly turn. The major fault line lies between the MILF, which at present enjoys Manila’s support, and the political clans entrenched in the region, who dominate the region’s power structures and resources, and do not welcome the arrival of a new political force on their traditional turf. The rift was already evident during the municipal and village elections in 2022 and 2023, respectively, but it is widening ahead of the 2025 polls, when the MILF will square off against its opponents for control of the new permanent authority. It is by far the group’s most significant test to date at the ballot box. Both sides are already forming coalitions in preparation for a showdown, and new political parties will be joining the fray in coming months. Given the stakes, and past episodes of political violence, the risk of unrest before the elections is clear.

Adding to the uncertainty are delays in “normalisation”, an ambitious process spelled out in the peace agreement that aims to demobilise rebels, boost economic development (with a focus on MILF-dominated areas) and achieve transitional justice. Around 26,000 ex-combatants have already laid down their arms, but the last phase of the MILF’s disarmament, which covers 14,000 fighters and over 2,000 weapons, is facing hurdles. Rebels are hesitant to give up their guns without getting the complete compensation packages outlined in the accord, which are to help them reintegrate fully into law-abiding society. A long-awaited meeting between the sides to thrash out a way forward is scheduled for February. Initial meetings on the level of technical working groups are a good sign, but barring a breakthrough, full disarmament before 2025 remains unlikely.

A third problem is the pace of socio-economic development in MILF camps and communities, also known as camp transformation, which has been sluggish. Many villages are still mired in poverty and lack essential services, leading to frustration that the promised peace dividends have not appeared. Other components of normalisation, including measures dismantling private armies and providing for transitional justice, are also lagging.

What the EU and Its Member States Can Do

The EU has generously financed the Bangsamoro peace process for over a decade. At present, its funding portfolio focuses on three areas: governance and institutional support for the interim government; normalisation, with interventions in matters ranging from camp transformation to security (such as training joint peacekeeping teams in civilian protection or helping dispose of landmines); and humanitarian, development and peacebuilding projects. It also pays for smaller peacebuilding and education initiatives led by civil society, including youth and women’s organisations.

The breadth of this assistance has made Brussels one of the largest international donors supporting the Bangsamoro transition. But gaps remain in addressing the region’s needs after decades of war, and the EU could take further steps at this critical time.

Brussels should continue nudging [all parties] toward agreement on how best to fulfil the 2014 accord’s promise and bring about a peaceful Bangsamoro.

First, diplomacy is crucial: Brussels should continue nudging the Philippine government, the MILF leadership and high-level local officials as well as Bangsamoro civil society, including women’s organisations, toward agreement on how best to fulfil the 2014 accord’s promise and bring about a peaceful Bangsamoro. It should stress to all the need to resolve the difficulties in the transition in a way that prevents recourse to violence and includes all social and political constituencies. It is important that the outreach include a public component. European diplomats should pay regular visits to Cotabato City (the region’s de facto capital), MILF camps and EU project sites to demonstrate their governments’ commitment to the peace process. The EU and member states should also use every opportunity to urge Manila to meet its financial obligations related to normalisation, particularly as regards delivery of compensation packages to demobilised combatants. All these steps will give the Bangsamoro’s people greater confidence in the prospect of lasting peace.

Secondly, Brussels should also continue funding the Third Party Monitoring Team, the official peace process observation mechanism set up by the government and the MILF. The Team’s job is to review and assess progress in carrying out the peace agreement’s provisions and to update the public on the developments.

Thirdly, the EU and its member states should explore the possibility of allocating more resources to development initiatives associated with the peace process. The requirements for completion of the peace process, especially when it comes to normalisation, are considerable. Generating more money for camp transformation – either through the EU’s own projects, the multilateral Normalisation Trust Fund (tasked with coordinating donor assistance) or the UN agencies involved – would be a big step forward. The EU should also consider providing more support to local groups and individuals, such as community-based organisations or skilled technocrats working to resolve conflicts over land, efforts that are often neglected due to the sensitivities of local elites, including traditional politicians as well as influential MILF leaders. It could fund research on land ownership to help the regional ministries involved in land governance, organise training for local government officials on resource management, and offer technical assistance to existing peace mechanisms and ministries dealing with the issue.

Fourthly, the EU and its member states should support as much as possible the local civil society groups working on community peacebuilding and reconciliation as well as women-led organisations, especially in areas, like those in central Mindanao, still suffering high levels of violence. Brussels should, in particular, use its regional Foreign Policy Instrument not only to continue assisting counter-terrorism, human rights and gender-focused projects, but also expand its range to include crisis prevention initiatives ahead of the 2025 elections.

These last projects could include mediation and conflict resolution of community-rooted disputes involving armed outfits, on both the regional and municipal levels, and should lend technical support to Indigenous peoples, who are often caught between warring factions, including the MILF and other Moro groups. Assistance could encompass capacity building for local Indigenous officials and funding for civil society groups working to allay the mistrust between Indigenous peoples and armed actors. In parallel, the EU should prepare to assemble contingency funds for local humanitarian responses to emergencies – whether natural disasters or eruptions of armed conflict – that may befall Mindanao in the run-up to the 2025 polls. Finally, considering its relevant expertise, it should contemplate sending an observation mission for those elections, beginning discussions with Manila about feasibility at the earliest opportunity.

Europe and Central Asia

Toward Normal Relations between Kosovo and Serbia

Since taking office in 2021, the government of Kosovo’s Prime Minister Albin Kurti has been turning up the heat on the four northern municipalities where ethnic Serbs are in the majority. Kosovo’s refusal to grant greater autonomy to its ethnic Serbian population has been one of the two primary issues that keeps it at odds with neighbouring Serbia, from which it formally declared independence in 2008. The other is Serbia’s refusal to recognise Kosovo’s status as an independent state, which is essential to unlocking membership for the latter in international organisations like the European Union and UN.

As these disputes have lingered without resolution, Serbia and Kosovo have exercised a form of overlapping sovereignty in the north – with Serbia supplying education and health care to the residents, and Kosovo in charge of law enforcement and the courts – but Kurti has clearly lost patience with that arrangement. Among other things he has deployed heavily armed police to the region, placed an embargo on Serbian goods the residents need, evicted Serbian institutions and banned the use of Serbian currency. His government has justified these steps partly by citing security threats, most recently in the form of Serb paramilitaries whom it discovered bringing in military-grade weaponry from Serbia in September 2023.

Under this sustained pressure, over 10 per cent of Kosovo’s Serbs have emigrated over the past year. The departures accelerate a pre-existing trend: Crisis Group estimates that up to one third have left in the past eight years. The Kosovo Serbs’ emigration is worrying both because of what it says about their levels of frustration, and because it undermines the most plausible pathway to normalisation, in which Kosovo would give its Serbs significant self-rule in exchange for de facto if not de jure recognition by Serbia.

To facilitate better dynamics between Kosovo and its Serb population, the EU should:

- Encourage Pristina to refocus policing in the northern municipalities on meeting community needs. Special militarised deployments should not be used for day-to-day policing and instead should focus on border security and searching for weapons caches. Pristina should send more Serbian-speaking officers to the region (in contrast to those who speak only Albanian) and engage in outreach to improve relations with residents.

- Work to ensure that the needs of Kosovo’s northern Serb minority, especially in employment, health care and schooling, are met. If that cannot be done within the framework for partial autonomy that has been under discussion for Serb-majority municipalities (which the Serbs call a “community” and the Kosovars an “association”) then the EU and member states should press the parties to develop alternative ways to achieve the same goal.

- Encourage Pristina to soften its harsh security measures in the north, including through the withdrawal of special police deployments, promising relief from sanctions and lesser measures in return.

- Press Serbia to cooperate fully with efforts, including those by KFOR, the NATO-led peacekeeping force in Kosovo, to seal the border to arms smuggling and to locate heavy weapons it has supplied to Kosovo Serb paramilitaries.

Echoes of Conflict

Since the 1999 conflict that saw Kosovo separate from Serbia, there has been an unresolved question about how the government in Pristina (which represents a majority Albanian population) will govern the four Serb-majority municipalities in Kosovo’s north. Though Kosovo and Serbia had developed a modus vivendi for administering and supplying services to these communities, that has significantly unravelled since President Kurti took office in 2021.

Pursuant to the governance arrangements that emerged over the years prior to Kurti’s election, Kosovo and Serbia were both able to exercise certain sovereign powers over the four Serb-majority northern municipalities. The municipalities had parallel municipal governments, one in each system, each with its own official website. Residents could get both Kosovo and Serbian personal documents. Under this modus vivendi, Belgrade and Pristina provided redundant services in some areas but divided responsibilities in others. Serbia had the bigger footprint, running schools and the health care system; Kosovo retained control of the police and courts.

In 2021, Pristina began enforcing its authority in northern Kosovo by deploying to the region a large, militarised special police force.

After Kurti came to power, however, that started to change. In 2021, Pristina began enforcing its authority in northern Kosovo by deploying to the region a large, militarised special police force, which was greeted with predictable hostility by the population. Over the next two years, Pristina also banned goods and medicines from Serbia, expropriated land for special police bases, stopped construction of Serbian-funded housing, evicted Serbian institutions from office buildings, and demanded that drivers use Kosovo-issued licence plates (instead of Serbian ones) or face fines or confiscation of their vehicles. The measures prompted a boycott and mass resignations by ethnic Serbs from public roles and offices. Locals put up barricades and mobilised the population. Police and Serb outlaws began to exchange gunfire frequently. At the end of May, Pristina took control of municipal buildings in the four northern municipalities, sparking violent protests and leading KFOR, the U.S.-led NATO peacekeeping force, to intervene.

Things then went from bad to worse. In September, Kosovo police stumbled upon a group of Serb paramilitaries while they were sneaking in weapons near the northern village of Banjska. A police officer was killed when an anti-personnel mine laid by the paramilitaries exploded and at least three Serb fighters were shot dead in the ensuing firefight. Following a tense standoff, and with KFOR peacekeepers helping to prevent an escalation, the paramilitaries pulled back to the hills. Much remains a mystery about the paramilitaries and their goals. Many of the weapons they had smuggled in would have been useful for setting ambushes (mines and other explosives) and shooting at Kosovo forces from a distance (rocket-propelled grenades, mortars and sniper rifles). They may have planned a guerrilla campaign designed to push the Kosovars out of the Serb-majority areas – or to encourage KFOR to interpose itself along the de facto ethnic boundary separating northern from southern Kosovo.