Throughout its 185 years, The Baltimore Sun has served an important role in Maryland: uncovering corruption, influencing policy, informing businesses and enlightening communities. But legacies like ours are often complicated. We bore witness to many injustices across generations, and while we worked to reverse many of them, some we made worse.

The newspaper’s founder, Arunah S. Abell, is credited with bringing affordable and independent journalism to everyday citizens in Baltimore, beginning in 1837, at a time when newspapers were focused on moneyed, merchant classes and special interests. But like others in this country during that time, Abell was a Southern sympathizer who supported slavery and segregation. And this newspaper, which grew prosperous and powerful in the years leading up to the Civil War and beyond, reinforced policies and practices that treated African Americans as lesser than their white counterparts — restricting their prospects, silencing their voices, ignoring their stories and erasing their humanity.

Instead of using its platforms, which at times included both a morning and evening newspaper, to question and strike down racism, The Baltimore Sun frequently employed prejudice as a tool of the times. It fed the fear and anxiety of white readers with stereotypes and caricatures that reinforced their erroneous beliefs about Black Americans.

Through its news coverage and editorial opinions, The Sun sharpened, preserved and furthered the structural racism that still subjugates Black Marylanders in our communities today. African Americans systematically have been denied equal opportunity and access in every sector of life — including health care, employment, education, housing, personal wealth, the justice system and civic participation. They have been refused the freedom to simply be, without the weight of oppression on their backs.

For this, we are deeply ashamed and profoundly sorry.

Our contribution to this maltreatment is a dark and disgraceful component of The Sun’s past. As an institution, we’ve called on many others to recognize and rectify their own bigoted practices, past and present, particularly in these recent years of a national reckoning on race. It is our responsibility to do the same within our own walls.

We have made efforts before to bolster diversity and inclusion, but the evolution has been slow. The death of Freddie Gray while in Baltimore police custody in 2015, and the national light it shone on the persistent disparities in the city, shook us out of our complacency. And, as a movement grew across the country, as more Black Americans died at the hands of police — Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, Breonna Taylor, Anton Black, George Floyd — so did our obligation to scrutinize The Sun’s past.

And so, now we turn the spotlight on ourselves and our institution, looking at our history through a modern-day lens in an attempt to better understand our communities, the effect we have had on them, and the distrust engendered by The Sun’s actions. As part of that process, members of The Sun’s editorial board and its Diversity Committee, made up of staff volunteers, consulted the paper’s archives and several other archives online, including newspapers.com and ProQuest, which we accessed through the Baltimore County Public Library. We found appalling coverage that clearly furthered prejudice and alienated many of our readers.

Among the paper’s offenses:

- Classified ads selling enslaved people or offering rewards for their return, the first of which appeared just two months after the paper’s launch in May 1837;

- Editorials in the early 1900s seeking to disenfranchise Black voters because, as The Sun opinion writers wrote, “the exclusion of the ignorant and thriftless negro vote will make for better political conditions” and to support racial segregation in neighborhoods to preserve what Sun writers called the “dominant and superior” white race;

- A failure to hire any African American journalists before the 1950s, and too few Black journalists ever since;

- The identification of Black people by race in articles into the early 1960s, until progressive readers threatened to cancel their subscriptions if the labels weren’t removed;

- A reliance by too many of us for too long on the word of law enforcement over that of Black residents who said they were being improperly targeted by police;

- A 2002 editorial dismissal of African American lawyer Michael Steele, running mate to gubernatorial candidate Robert Ehrlich, as bringing “little to the team but the color of his skin”;

- A dearth of stories about issues relevant and important to non-white communities, and a failure to feature Black residents in stories of achievement and inspiration, rather than crime and poverty, on a level proportionate to that of their white counterparts.

The paper’s prejudice hurt people. It hurt families, it hurt communities, and it hurt the nation as a whole by prolonging and propagating the notion that the color of someone’s skin has anything to do with their potential or their worth to the wider world.

The Sun’s bigotry also hurt its business. It cost the paper readership and community credibility, particularly in Baltimore City, where the African American population swelled from about a fifth of residents when Abell founded the paper, to more than 60% today. Distrust of The Sun has been handed down through generations of Black Marylanders, deservedly so.

We who make up The Sun today are committed to atoning for the paper’s past wrongs regarding race and have taken steps toward an intentionally inclusive future in our pages and professional practices. We know it’s not enough to simply avoid doing further harm by rejecting stereotypes; we must actively work against them by reflecting and promoting the experiences of the full spectrum of our population, across racial, religious, economic, sexual and social boundaries.

In recognition of this, the paper has taken a number of steps over the past several years. They include:

- Launching a Diversity, Equity and Inclusion reporting team focused on telling the stories of underserved groups;

- Developing a cultural competency style guide to help ensure that our coverage of Black, Hispanic, Latino and Asian American communities; Indigenous people; people with disabilities; and LGBTQ+ individuals is respectful, accurate, inclusive and fair;

- Building a database of sources made up of people of varying backgrounds to diversify the voices who bring analysis and insight to our stories;

- Nurturing a talent pipeline to broaden the pool of applicants we promote and hire from: From 2018 to 2021, the percentage of non-white people who make up the newsroom rose from 20.7% to 26%, and of the 26 people we’ve hired over the past two years, 13 of them — 50% — have been people of color;

- Partnering with the Robert C. Maynard Institute for Journalism Education, a nonprofit training organization, to provide diversity and bias education for the staff, and to audit content across Baltimore Sun Media properties to gauge how well our reporting and opinion coverage reflects the variety of race, class, gender, generation, geography and sexual orientation in our communities;

- Forming outreach committees to engage with groups we have inadequately served in the past to find out how we can do better. Among those contacted were Black funeral home directors, some of whom told us they didn’t believe we would welcome their input or feature news obituaries of African American residents;

- Making a point of diversifying the photos we publish to better represent the communities we cover.

Our approach today, unlike that of the country’s “colorblind” era of the 1980s and ‘90s, is to actively see the differences among us and work to understand: why they exist, what they mean to whom and why, whether they’re real or perceived, and whether they should be honored or struck down. Pretending we were all the same never worked, because it ignored the fact that we’re not all given the same opportunities to succeed or fail on our merits; some are privileged, others are oppressed. Refusing to recognize that only prolonged difficult conversations and much-needed soul-searching, dooming more generations to repeat the cycle.

As journalists, as the Fourth Estate, we at the paper have a public responsibility to confront and illuminate societal ills so that they can be addressed and eradicated. On race, The Sun’s history is one we’re not proud to share, and we should warn you that it’s offensive to read. But addressing one’s wrongs begins by acknowledging them. While we’ve taken great pains to highlight the paper’s righteous actions through the years, and there have been many, we have yet to shine a light on our dark corners — until today. This accounting is most certainly incomplete. Nevertheless, we hope that by revealing some of our institution’s past injustices, we will step closer to truly providing, as our masthead says, “Light for All.”

— The Baltimore Sun editorial board

‘$300 for the return’ of Matilda

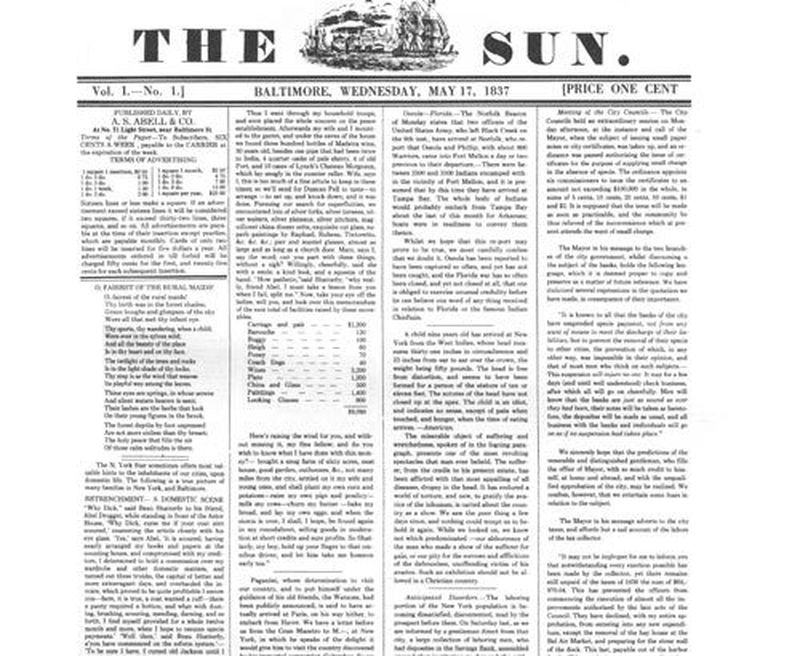

When the first issue of The Sun rolled off a hand-operated press in May 1837, an editor’s note from founder Arunah S. Abell promised that the penny publication would, “without fear or partiality,” work toward “the common good.” And it did, in many ways. But in the one way that arguably counted the most — integrating our population and lifting it as a whole — the paper failed devastatingly.

Though born and raised a Northerner, Abell, who was white, had strong Southern sympathies, and his newspaper perpetuated and profited from the brutal enslavement and sale of Black people up to and through the Civil War. At the time, Baltimore acted as a hub for the slave trade, with dealers bringing captive people into Maryland, imprisoning them in pens around the city’s harbor, then transporting them on packet ships down the Chesapeake Bay to Southern markets. The Sun profited from the misery, running advertisements from dealers and others.

One ad from October 1849, placed by an Elkridge man, offered $300 for the return of a 30-year-old “bright, Mulatto Negro Woman, named MATILDA,” who escaped in a horse carriage with her husband, a free man, and five children, ages 10 months to 10 years. On the same page, a 12-year-old girl is offered for sale. The ad reads: “She is honest, healthy and active; well acquainted with house work. A good home is wanted for her. Apply at the Sun office.”19 Oct 1849, Fri The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Maryland)Newspapers.com

Slavery and attitudes toward it would politically divide the country over the next several years, with a new anti-slavery Republican Party quickly gaining supporters in the North and detractors in the South. By 1860, most Southern states were promising to secede from the Union if Republican Abraham Lincoln won the presidency, which he did in November of that year. The Sun strongly criticizedLincoln’s election, claiming the new president would “rule with authority” over slave states that rejected “his principles and avowed policy as in direct conflict with their constitutional rights.”

Though Maryland was a slave state, it voted against secession, which put it on the Union side by default. Once the Civil War began, with four times as many Maryland men fighting for the Union as the Confederacy, and under threat of jail from federal authorities, Abell held off from both pro-Confederate and anti-Lincoln commentary in The Sun. After the war ended and the Union won, the paper accepted the outcome as a practical matter. But instead of focusing on integration, it frequently sought to advance segregation and cement the idea that Black citizens were second-class at best.

‘Purify the electorate’

In 1887, as Jim Crow laws were put in place to counter gains made by Black Americans during Reconstruction, a Sun news brief hailed the unveiling of a memorial to Roger B. Taney. He was the U.S. Supreme Court chief justice from Maryland who wrote the infamous 1857 Dred Scott decision claiming that Black Americans had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect” and were not included in the Founding Fathers’ declaration that “all men are created equal.”

The Sun called the installation of the statue “an event of great interest to our people” and noted that the Dred Scott decision, which Maryland judges largely eschewed, was “in strict agreement with the constitution” and that Taney was “brave, pure and learned.”12 Nov 1887, Sat The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Maryland)Newspapers.com

(That’s in sharp contrast to the paper’s position today. When the Taney statue was removed in 2017, along with three Confederate monuments, The Sun’s editorial board said they never should have been erected in the first place.)

As the 1800s gave way to the 1900s, Democrats were in control of Maryland’s government, and they fought hard to disenfranchise Black voters, who largely supported the Republican Party at the time, introducing amendments over several years meant to prevent Black people from voting.

On Page 5 of the Oct. 31, 1909, morning edition of The Sun, in large type that spread across two columns, the paper made its case for why the “suffrage amendment” on the table that year, which would have required voters to pass a sort of writing test before being granted the right to cast a ballot, should be ratified. Unlike today’s efforts to disenfranchise minority voters, there is absolutely no attempt to code the language of the argument. It comes out swinging against Black Marylanders and never lets up, calling them ignorant, thriftless and a threat to “better political conditions.”31 Oct 1909, Sun The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Maryland)Newspapers.com

And, in case that didn’t make the point, the paper followed up on Election Day with a “last word” for the “intelligent white voter.” It urged him to “purify the electorate” by voting for the suffrage amendment: “You can make Maryland a white man’s State, and make each and every white man’s vote count instead of being killed by an illiterate negro’s ballot.”

‘The encroachment of the negroes’

The next year, the paper wrote glowingly in its news pages of a segregation ordinance — “preventing negroes from moving” into majority-white neighborhoods and vice versa — signed into law in 1910. The measure was drafted, one article claimed, after white residents in the northwest section of the city decried “the encroachment of the negroes into white residential sections, lowering property values and driving white people from the neighborhoods in which, previous to the black invasion, they had liked to live.”

As Antero Pietila, a former Sun reporter, noted in his 2010 book, “Not in My Neighborhood: How Bigotry Shaped a Great American City,” that particular ordinance paved the way for residential segregation in America. Nothing else like it was on the books anywhere, and legislation modeled after it soon sprung up in other regions of the country.

The ordinance was eventually struck down, as were others that followed, by a 1917 Supreme Court ruling concerned that the measures limited the ability of white homeowners to sell to whomever they wished. But The Sun remained a strong proponent of segregation — including segregation contained within “voluntary” neighborhood covenants in which white residents agreed not to sell to Black buyers (these, too, were eventually struck down by the high court, in 1948). And its writers complained of the “negro invasion” for nearly two decades.

In the 1930s, as the Democratic and Republican parties began the slow philosophy swap that would come to represent them today, it appeared as if The Sun had a moral awakening. It gave front-page news coverage to two horrific lynchings on the Eastern Shore, and took strong positions against them in editorials. Sun columnist H.L. Mencken wrote so derisively of Salisbury’s white population and town leaders, he was threatened with death should he show his face there.

But the coverage, as our editorial page later noted in 2018, “deplored the inhumanity of the perpetrators without ever really acknowledging the humanity of the victims” or the community terrorized by their brutal deaths. The ire was directed at the “poor, white trash” killers, as Mencken put it; there was no empathy for — or even real interest in — the Black victims. (This was also the decade that the paper featured an offensive recipe column, written insultingly and proudly by a white woman “in the vernacular of an ante-bellum mammy.”)

And in the early 1950s, the editorial board bemoaned the banning of the decades-old pro-Confederacy and pro-Ku Klux Klan film “The Birth of a Nation.” After Maryland’s Board of Motion Picture Censors deemed the movie “morally bad and crime-inciting,” The Sun defended it as simply trying to depict sentiments of the South during the Reconstruction era.

‘Painful to many Marylanders’

And as court rulings began to reveal the lie in the notion of “separate but equal” education, The Sun was reluctant to endorse the obvious. In 1952, when Baltimore Polytechnic Institute high school allowed 10 academically qualified Black students to enter its accelerated “A course” program, after determining that a separate program would not provide equal educational opportunity, The Sun congratulated the school board on its “conscientiousness and restraint” in handling the matter, but failed to note the historic nature of the integration or even the appropriateness of the decision.

When two years later, the U.S. Supreme Court, struck down the separate but equal doctrine and outlawed segregation in its Brown v. Board of Education ruling, The Sun, while acknowledging that the decision must be accepted and was “inevitable,” editorialized that it also would be “painful to many Marylanders.” The bright side, the writers found? It might decrease the ”criminal activity to which too many of the Negro race are given.”

At that time, The Sun was still choosing to identify Black people by race in its coverage — and only Black people — placing the tag “Negro” after individual names, even though many other newspapers had long since stopped similar practices. When a Westminster minister and seminary professor asked the paper to discard “this discriminatory practice” in 1955, according to an article in The Afro-American, the editor-in-chief flat out refused, self-righteously declaring that “the Sunpapers will not be a party to such suppression” of fact and that “the matter of what it is now fashionable to call ‘pigmentation’ is important from both the white and the Negro point of view.”

He didn’t spell out what, exactly, was so important. But he did mention crime and Black responsibility for it, so we’d venture a guess that the significance was in perpetuating a stereotype of Black people as dangerous and to be feared. At the time, Baltimore’s population was about 24% Black, and white fear of “the other” was strong. Several years would pass, and a new editor-in-chief would ascend, before the paper eliminated the automatic race tags, in 1961, under pressure from readers who were sick of them.

As the civil rights movement grew throughout the 1960s, so did The Sun’s conscience. In 1964, a decade after the Brown v. Board decision, editorial writers produced a fiery piecedenouncing Alabama’s segregationist governor, George Wallace, and decrying school segregation as a “caste system that has kept Negroes in a position of inferiority.” The same editorial embraced the Civil Rights Bill of 1964 working its way through Congress as a “national commitment to sweep away the inequities which racial discrimination has imposed on a large body of citizens” that is “right and inevitable.” And when the bill passed in June of that year, editorial writers called it “a mighty step” and “a reaffirmation of the principles of equality upon which our society was founded.”

‘Voice of inspiration for millions’

Opinion writers also recognized the genius and dedication of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. — to a point. They praised his clear plan and commitment to nonviolent civil rights advocacy, but chafed when he proposed action outside that realm, such as marching in support of home rule for Washington, D.C., or encouraging resistance to the Vietnam War draft. When King was assassinated April 4, 1968, the front pages of The Sun and The Evening Sun the next day underscored the significance, with headlines urging peace and proclaiming the “whole world stunned.” The editorial board called the assassination a “national tragedy,” noting that King was “the voice of inspiration for millions.” There was “none other of his stature,” they wrote. The editorial cartoon that day featured a headstone and King’s name, with the epitaph: “Killed in the cause of equality.”

By April 6, a violent backlash had begun in Baltimore and across the nation, with irate crowds taking to the streets and burning buildings out of frustration, becoming a backdrop to congressional consideration of the 1968 Civil Rights Act. The Sun urged the bill’s passage, saying that the “public officials who say now that the bill ought to be defeated because of the riots are acting like children.”

Like the uprising in 2015 following Freddie Gray’s death, the 1968 unrest drove news coverage for months, as officials and media dug into the issues underlying it. But how much of an effect it had on Sun coverage going forward is hard to gauge. The newspaper’s opinions grew progressively more supportive of racial equality, though changes within the paper were subtle. The Sun hired its first Black female journalist in 1973, but the staff was — and still is — overwhelmingly white, compared with the makeup of the community; this is especially evident in The Sun’s leadership teams through the years.

By the 1980s, Sun editorials focused on issues of poverty, criminal justice and equal opportunity in hiring through a lens of race, but they still had an ivory tower quality to them of being written by someone largely disconnected from the topic. In a December 1981 editorial, writers decried strict welfare rules that hurt the working poor, but made a point of separating them from people “on the dole,” seemingly buying into the mythology of the “welfare queen” popularized by Ronald Reagan during his 1976 presidential campaign.

And in 1989, after the personal journals of H.L. Mencken were released, revealing deep-seated racism and antisemitism, Sun writers undertook great efforts to make excuses for the revered writer, even though Mencken had been dead for nearly 34 years. “The fact that the sage of Baltimore had unkind things to say on a broad range of topics can hardly come as a surprise to those familiar with his sharp and biting work,” wrote one columnist. “They make him a more complex figure, more difficult to decipher.”

The Sun would continue to sponsor a writing contest named after Mencken, despite protest from some award recipients. And more than a decade later, it would install a Mencken quote on its lobby wall on North Calvert Street, showing, in the most generous interpretation, a lack of self-awareness and sensitivity.

Black Lives Matter

Shortly after the diary release, in 1991, the vicious beating of Rodney King by Los Angeles police officers was recorded on video and broadcast across the country, and white Americans could no longer deny that Black people were being mistreated by law enforcement. Yet, The Sun would continue to take the word of local law enforcement over Baltimore residents in its reporting for decades to come, largely without question. It did this even as the city adopted a “zero tolerance” style of policing in the late ‘90s that the U.S. Department of Justice would later find “led to repeated violations of the constitutional and statutory rights” of community members.

Though people like state Sen. Jill P. Carter, who’s long been in the Baltimore political scene, had for years been raising alarms over police brutality and the need for reform, it wasn’t until 2014 that The Sun took an in-depth look at why it was that the city was paying out millions of dollars to settle dozens of lawsuits by Black residents who said police beat them up. That investigation won multiple awards for the paper, as good journalism has a way of doing, and was a prescient walk-up to the story that would dominate the paper the next year: Freddie Gray’s death.

The Sun’s coverage there earned it two Pulitzer Prize finalist honors, one for breaking news “reflecting the newsroom’s knowledge of the community and advancing the conversation about police violence” and one for the editorial board, for writing “that demanded accountability … while also offering guidance to a troubled city,” according to the prize committee.

When The Sun moved offices to East Cromwell Street in 2018, we covered one wall with a photo from a protest in Gray’s Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood. It shows a sea of mostly Black faces crowded together, beneath “Black Lives Matter” and “Stop Police Terror” signs. It’s a better reminder of what we are here to do than the Mencken quote for various reasons, not the least of which is that it’s about the people we serve, rather than about us. But a quote or a picture doesn’t a paper make. Actions speak louder than words, even in the newspaper business.

We’re still grappling with improving diversity in our staff and our coverage. Reporting that arises directly from sources in the region’s Black communities has long been lacking in The Sun, largely because the connection is lacking. We’re not out there enough, and we’re not trusted enough. We are working on that, and looking into an impression some hold that The Sun is harder on Black officials than white. Unlike in years before, we’re talking about these issues — routinely — and how to address them.

To that end, we ask for your input, as readers and community members. How can we better connect? How can our reporting be more relevant? How can we better serve? What wrongs have we yet to right? Please share your thoughts on our past, present or future at talkback@baltimoresun.com, with the word “apology” in the subject line. Some responses will be compiled for publication, but we will read and consider all of them.

We are your newspaper, and we want to serve your interests and that of the public good as a whole.