Ms. Cheeks is the author of the novel “Acts of Forgiveness.”

In my debut novel, a family retraces their lineage in order to be eligible for the nation’s first federal reparations program for Black Americans. When I was selling my novel in 2021, it was pitched to publishers as “speculative fiction, but only slightly.” I hadn’t specifically identified that genre, but I could see how it made sense: Up to that point, only one U.S. city, Evanston, Ill., had actually issued reparations in the form of housing grants. The idea that the United States could ever collectively support a national reparations policy for Black people seemed, well, the stuff of fiction.

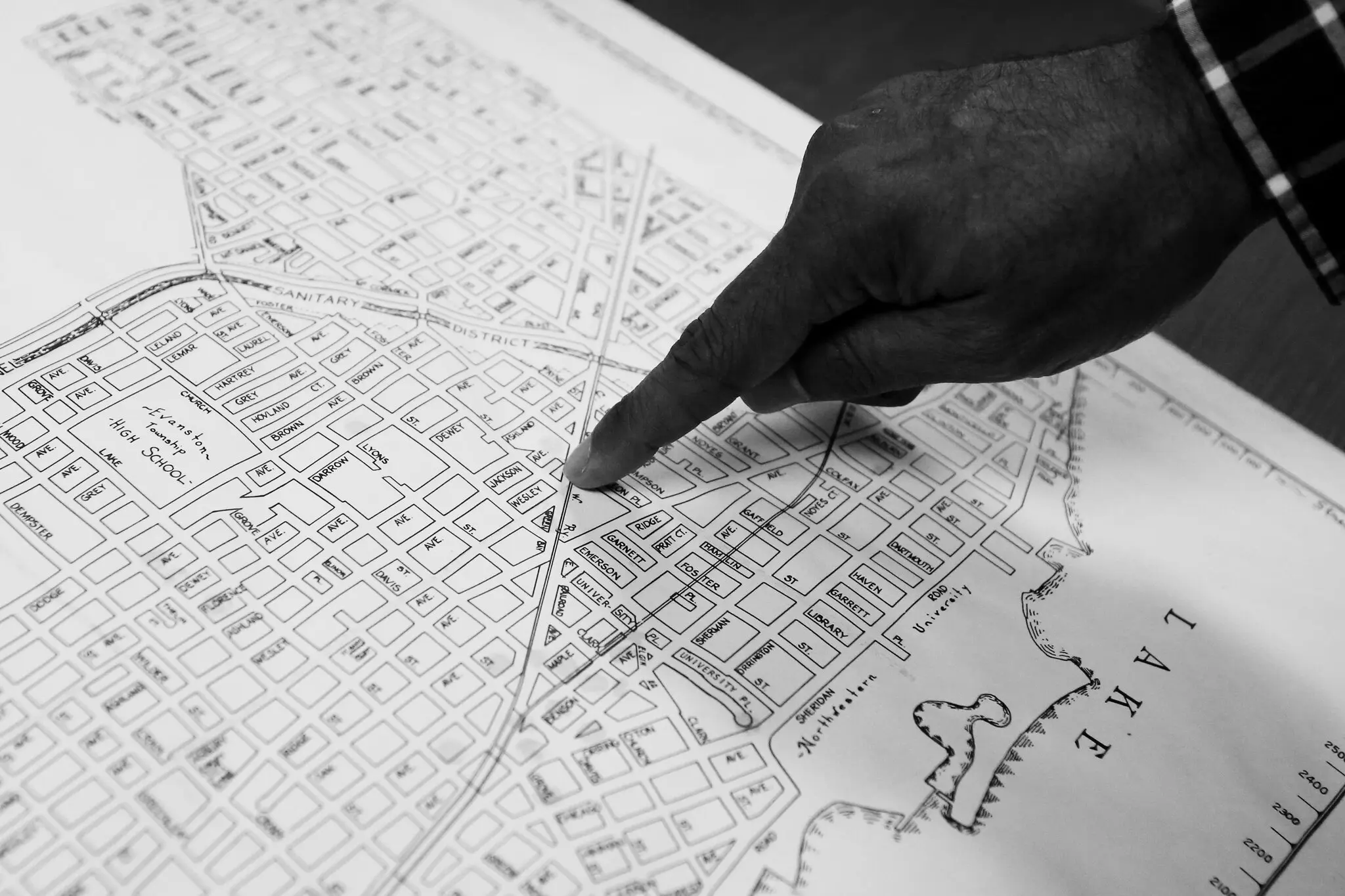

Since then, reparations task forces and commissions have been created in California, Illinois, New York and Pennsylvania. State and citywide reparations initiatives offer a unique opportunity: They can look at specific harms perpetrated in a community, like redlining or wrongful drug convictions, and offer redress for citizens and the families who lived there. In Evanston, for example, reparations are being funded through revenue generated from a cannabis tax. If you can prove that you were a Black resident of African descent between 1919 and 1969 or are the direct descendant of one, or that you suffered housing discrimination related to the city’s policies after 1969, then you are eligible for a payment. As of August, the city had distributed just over $1 million, with more funding on the way.

But what happens if you do not live in a community that pursues reparations? Slavery was a complex multistate system enabled by the federal government and protected by a sweeping body of law. The same government later promoted and propped up segregationist policies and failed to uphold the values of the 14th and 15th amendments across the Jim Crow South. To address systemic inequalities rooted in federal law, a federal reparations policy is required. One city, even multiple cities, or states, can’t compensate individuals for what an entire nation has done.

I decided to write about reparations after researching the racial wealth gap, the statistics of which continue to paint a picture of widespread systemic failure. According to the Federal Reserve’s 2022 Survey of Consumer Finances, the typical white family has about six times as much wealth as the typical Black family, despite the fact that between 2019 and 2022 the typical Black family’s wealth rose at about twice the rate of the typical white family’s during the same period. The Black-white homeownership gap has been little changed for decades; in 2021, according to the National Association of Realtors, the Black homeownership rate was 44 percent compared to 72.7 percent among White Americans. White college graduates have over seven times the amount of wealth as Black college graduates. If you believe the increasing wealth gap among Black and white Americans is worth closing (and, pointedly, not everyone does), then it’s hard to read these statistics without intuiting that a federal intervention must be part of the equation.

I am both encouraged by more local reparations policies and wary of what we lose if we rely on them alone. In my novel, I imagined a federal program because I wanted to explore how it could also facilitate psychological healing across generations. What might it mean for Black Americans to feel that their country sees their pain and wants to make it right? If we could acknowledge what we did wrong so that we could begin moving forward?

Sign up for the Opinion Today newsletter Get expert analysis of the news and a guide to the big ideas shaping the world every weekday morning.

Statistics are numbers that don’t tell the whole story. They don’t show what it’s like for a middle-class Black man wearing a hoodie to be denied entry to spaces that white people in the same attire are allowed to patronize. Or what it’s like for a Black woman with natural hair to receive sidelong glances in an interview and then be denied a job offer.