People did all they could. Tens of thousands died. Nothing would be the same.

It had been a snowy first week of February, an unforgiving wind whipping around the hills where Syria and Turkey meet.

In Afrin, in northern Syria, where war has worn on for years, Naeem Qassam had spent that Sunday clearing snow from local roads. He went to bed at midnight.

Not far away, Ahmed Saqar, a nurse at the hospital in Afrin, had spent much of the weekend with his family.

In the small of the night between Sunday and Monday, he woke to pray before sunrise. “Everything was peaceful,” he said.

Saqar went back to sleep.

Yasser Nemmeh, a leader of the White Helmets civil defense group, had patrolled two nearby towns on Sunday, checking on his workers, making sure everything was reasonably peaceful.

“Nothing to worry about,” Nemmeh concluded as he headed home to eat dinner with his family and put the kids to bed.

At 3 a.m., the night was finally his — “the only time I have for myself,” he said. He opened textbooks for his master’s degree studies in international relations, made some notes and drifted off to sleep around 4 o’clock.

At 4:17 on Feb. 6, three hours before sunrise, Nemmeh and millions of others were shaken out of their beds by an epochal earthquake, stretching across a land that had survived Roman domination and French colonizers.

“Everything is shaking,” Nemmeh said. He froze in the middle of his room. “It doesn’t make sense,” he thought. “I can’t make it make sense.”

Since 1900, in this region, one of the planet’s most active earthquake zones, there had been 21 earthquakes of 7.0 magnitude or higher. After this one hit — 7.8 on the scale, the strongest here since 1939 — nothing would be the same. More than 50,000 people were killed; countless buildings collapsed.

One month later, the death toll is still rising, mounds of rubble scar towns and cities, and rebuilding remains a distant promise. The geologists would explain that the disaster was the result of three tectonic plates that make up part of the planet’s crust bumping into each other, as the Arabian Plate bumped into the Eurasian one, pushing the Anatolian one toward the west.

The quake was the deadliest in Syria since 1822. In Turkey, it killed more people than any other earthquake in almost 1,500 years.

‘People were left to their fate’

At 4:17, something woke Saqar, the nurse. He opened his eyes, “and the house was moving,” he said. “It went one meter in one direction and then one meter in the other.”

He looked at his wife, then at his sons. “It was like the blood disappeared from them,” Saqar said. “Then I realized there were noises from outside too. Screaming.”

Fifty-five miles away, in Antakya in southern Turkey, Orhan, who declined to give his last name, was sleeping in bed with his wife when he felt it. He knew what it was. “I pushed my wife to the corner” of the bed, he said. “I told her to get out first so at least one of us survives.”

Murat Ulucay, a teacher, was staying at his ailing mother’s apartment with his wife and son in Adiyaman, a city of more than 290,000 in southeastern Turkey. Ulucay was asleep in the living room when he felt a big jolt. “The living room wall broke and I was thrown out,” he said in an Instagram post.

He found himself outside, in his pajamas. He later learned that his shouting had attracted two people, who carried him outside.

He tried to move, but “I saw that my hip does not come with me, my hip is broken,” he said. “I was shivering, shivering.” All around him, there was nothing but pieces of fallen apartment buildings, and the people who had lived in them, “all my family and neighbors,” now trapped under debris.

“As the morning light came in,” he said, “voices came from under the rubble … the voices of at least 15 people.” Ulucaywaited for help: “Twelve hours passed, 24 hours passed, 36 hours passed; no one came.”

He heard groans and saw people “running around without knowing what to do. … People were left to their fate.”

Finally, on the fourth day, he said, foreign rescue workers arrived. It was too late for Ulucay’s family: “My wife, mother, son were under the rubble. We could not intervene. My wife died screaming, she died screaming. In her hands were full clumps of hair that she pulled out.”

They all died — his mother, wife and son.

In the same city, a few miles north of the Euphrates River, it took five to 10 seconds for Ali Yolli’s seven-story building to begin buckling. Yolli, 28, awoke in his living room on the first floor, noticed the driving rain outside and dashed out into the pitch black as electricity went out across the city. He made his way to a fountain between the buildings in his complex, the only space that seemed safe from falling rubble.

Yolli’s parents sheltered near their washing machine, which plunged into the basement of their apartment tower, the Poppy building. They survived. But his two younger brothers, 21-year-old Hamza and 13-year-old Enes, died, asleep together in theirbedroom.

Outside, Yolli heard “a lot of screams and yells for help,” as other buildings in the complex — all named for flowers — collapsed. “All of those people died,” he said.

Eighty miles to the south, in Sanliurfa, Ibrahim Aydogan, 34, woke up to violent shaking. Jars fell in the kitchen, books fell off shelves. A couch was flung clear across a room. In those first moments, he said, “I had given up on everything, and believed I was going to die.”

Aydogan pulled himself together and ran to his building’s roof, figuring it was better to jump than to be crushed inside. But his building was among the ones that didn’t fall.

Qassam, the 44-year-old team leader for the White Helmets, awoke to find that “everything was moving.” His mother; his wife, Amna; and their three children — Kinana, 5, Mohamed, 11, and Mahmoud, 14 — woke too, and quickly began to cry as everyone heard screams from other apartments in the building.

In their fourth-floor apartment, Qassam’s family wanted to make a run for the stairwell — get out now, their instincts told them — but his rescue training kicked in: Don’t risk the stairs. “You have to stay put until the aftershocks stop.”

“We were all really scared,” Qassam said. “I kept trying to soothe them. I told them to hold hands and pray to God.”

In the northern Syrian town of Jinderis, Mohammed Sydo was working the night shift at a White Helmets office 45 minutes away from his wife and four daughters in Afrin. He was preparing for morning prayers when the ground started “moving below my feet, like someone was pulling a carpet from under me,” said Sydo, 40.

There was nothing to do but brace and seek something stable to hold onto.

Across an area almost as large as Montana, the night sky lit up with flashes of pure white and searing blue, all manner of electrical failures: transformers blowing, generators exploding.

Neighborhoods fell into blackness as streetlights flared, then toppled. It was still dark out and now it was dark inside too.

‘I didn’t want my children to die’

In Malatya, Turkey, as people ran out of their homes into the presumed safety of streets covered only by open sky, a man knelt in the middle of the snow-powdered road, then tipped onto all fours, pressing his hands against the pavement for stability.

With every toppling of a building, every pancaking of a multistory structure, every roof suddenly tipped diagonally, sheets of icy snow crashed onto the ground below. The snowy powder blended with billowing clouds of dust.

Dazed people, many in pajamas, staggered about, searching for relatives and clean air.

For millions of people, the street became the onlyshelter.

Nemmeh, the Syrian man who felt as if his brain were paralyzed in the first seconds of the quake, heard screaming. Only when the shaking stopped did he realize what was happening.

Instinctively, he pulled on his yellow and navy civil defense uniform and ran downstairs to grab his children. Hamzeh, 8, and Ammar, 13, “are awake and they are panicked,” Nemmeh said. “They are shouting at us, asking what is happening, what is happening? We scooped up the little ones” — Wissam, 1½, and Leem, 4 — “in our arms and we ran outside into the rain.”

He found his neighbors on the street, milling anxiously. No one knew where to go.

Saqar, the 54-year-old nurse, heard screams, then a much bigger sound: “buildings as they were crashing down,” he said. “I was trying to comfort my children, I was trying to stay calm. We’re a religious people and I just kept telling them that this is God’s work, God’s plan.”

But Saqar was terrified.“All I could think about was death, and I didn’t want my children to die,” he said. “My son, who is 19, and my daughter, who is 14, I needed to get them out.”

He hurried them out to the road, even as the ground kept swaying, making a noise like cogs straining against each other.

“People looked crazy with fear,” the nurse said. “It wasn’t even time for the fajr,” the dawn prayer, “but the streets were full with people running and yet not knowing where to go. Some people were running toward the mosque, some people were running in the other direction.”

Saqar, who lives five minutes from the hospital where he works, knew he was needed there, but he couldn’t go quite yet.

“The street was full of patients too,” he said. “I was giving first aid to everyone I could.” Entire families sat on the sidewalk, coated in thick gray dust, the essence of concrete and steel, remnants of their city. The blood on people’s faces looked black, not red.

“I had a first aid kit in my car,” Saqar said. “I was using the bandages from it, and helping who I could.”

The most popular and interesting stories of the day to keep you in the know. In your inbox, every day.

In Antakya, Orhan, the man who had pushed his wife out of bed so she might survive, watched as she made it out. He was stuck: “The ceiling had fallen on my head.” He prayed to God to die or emerge alive. He studied what was left of the room around him, planning escape routes, deciding he would try the window if he got a chance. He ended up enduring under the weight of the ceiling for 22 hours.

In Malatya, the 66 rooms of the glass-clad, six-story Avsar Hotel pancaked, plates of concrete falling atop each other in a slow-motion puff of destruction. “Modest quarters in a laid-back hotel,” a travel guide had said about the Avsar, where rooms went for $20 a night.

“Permanently closed,” its listing on Google says now.

‘Don’t be afraid’

Sydo, the White Helmets worker in Jinderis who was 45 minutes away from his family, knew not to stay inside. He and his fellow workers “were outside within seconds,” he said, in the cold and rain, surrounded by people “barefoot and in their pajamas.”

It felt to Sydo like “judgment day. … People told us later that the earthquake only lasted around a minute, but we could barely grasp that. It felt like 10 times that long.”

He couldn’t stop thinking about his children in their fifth-story apartment, more than 13 miles away. He wouldn’t be able to contact them for 10 hours.

Rescue workers on the Syrian side of the border found each other on WhatsApp:

4:25 a.m.: Peace be upon you. Guys, please update us. Have any buildings fallen? The earthquake was very strong.

4:26 a.m.:Declare a state of emergency quickly. Everyone needs to mobilize.

Before they could figure out where to go or how to help, the shaking began anew.

At 4:28, heavy aftershocks rattled people. Towers of flames lit up the sky, from gas lines, from power boxes, from buildings that caught fire.

Three hours later, the sun shed light on the devastation. In Gaziantep, Turkey, a Roman fortification’s stone walls had shattered and collapsed, two millennia of history reduced to rubble. Mosques, apartment towers, shops were now just piles of stones.

Minutes after the quake, Abeer Zleito, a 37-year-old Syrian teacher whose family had been displaced to Turkey by civil war, was at home in Yayladagi, just north of the border, with two of her children. She began sending messages on WhatsApp to her husband, Hussam, an aid worker who was across the border in Syria.

4:40 a.m.: How are you

Did you feel

the earthquake

it’s very strong

4:43 a.m.: hey where are you

4:44 a.m.: here they turned on the danger siren…

4:46 a.m.: why aren’t you answering

4:47 a.m.: there are buildings that collapsed…

4:49 a.m.: oh kind one be kind [a supplication to God in the face of bad news]

we’re very afraid

5:29 a.m.: what happened where are you guys

6:41 a.m.: reassure us

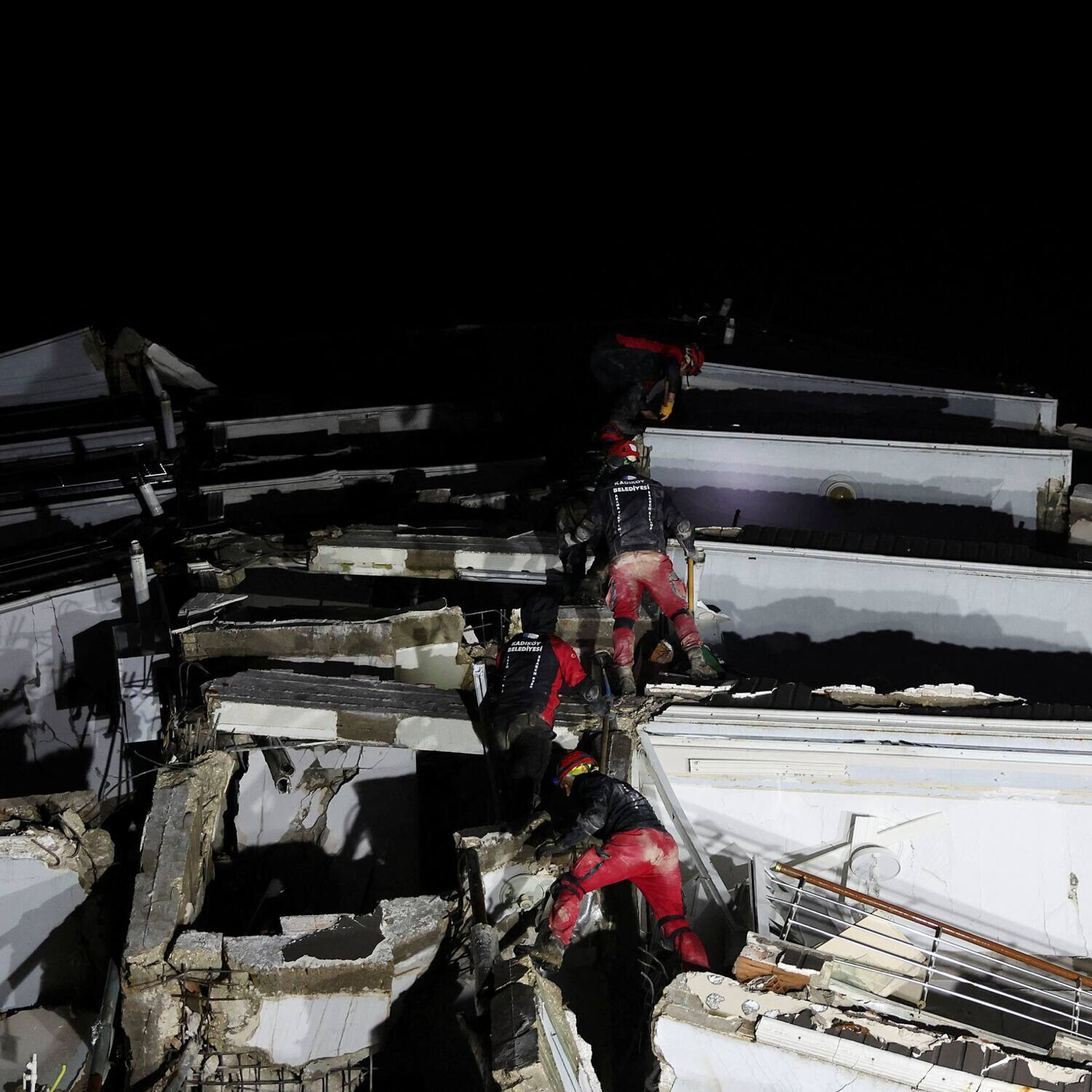

When the quake struck, Hussam sent a quick message to his family that he was alive, but it didn’t arrive until he reconnected to the internet hours later. In the meantime, he had to dive into the rubble. He dug through rocks, dirt and concrete, pausing only to listen for voices from inside the pile.

He couldn’t stop worrying about his family. Hours later, he ran to find a spot with a working signal and returned his wife’s urgent messages:

4:08 p.m.: hello my love

tell me how you’re doing

4:09 p.m.: I am well thanks to God

Hussam returned to the pile, toiling for five hours to extract one woman, pumping oxygen to her until she could be pulled from the ruins of her home.

Most were not so lucky. Hussam and fellow rescue workers found more than 20 people dead, most of them children.

There was no safety on either side of the border. Around 1:30 p.m., the earth would rumble once more, sending structures tumbling again.

In Malatya, Yuksel Akalan, a TV reporter for the Turkish station A News, was broadcasting live from the scene, walking toward the rubble to show viewers the rescue operations, when the second quake hit, this one measuring 7.5.

He saw a young woman struggle to pull two children away from a rubble pile and into the open street. “Come, come,” he called out. He turned away from his camera and ran toward them, lifting the older child up and carrying her toward a calmer space.

“Come quickly,” he said. “Come wait in an open area. Don’t be afraid.”

The girl wept, grabbed hold of the reporter’s shoulders, scanned around for her mother.

“There is nothing to be afraid of,” the reporter assured her. “Look at me, don’t be afraid. It has passed.”

In Turkey and Syria, people waited for the shaking to subside.

Then they went back to digging through the wreckage and searching for the lost.

Reem Akkad in Washington and Mustafa Salim in Baghdad contributed to this report.