It’s past time for us to ditch the damsel narrative, admit our power, and stand up for racial justice.

Over the holiday weekend, two instances of racial discrimination — one that turned deadly, and one that easily could have — set social media aflame before becoming headline news. On Monday, a white woman named Amy Cooper allowed her dog to run freely in the historic Ramble of Central Park in New York before a black man named Christian Cooper (no relation) requested that, in accordance with the area’s rules, she put the dog on a leash. Christian, a birder, knew that loose dogs could damage the plants and startle animals native to the park. In a video now seen around the world, Amy threatens to call the police and report that an “African American man is threatening my life” — which she does, hiking up her voice to a terrified high pitch.

That same day, another video made the rounds: In Minneapolis, a black man named George Floyd was slowly choked to death by a white cop with a knee to his neck. His last words were the same as Eric Garner’s, who also yelled out “I can’t breathe” while begging for release from a police officer’s chokehold in 2014. This was yet another modern-day lynching, yet another black person’s humanity reduced to a hashtag, yet another example of structural racism and an all-powerful police state targeting black communities and destroying black life. A police officer killing a black man for threatening the white supremacist capitalist order (by allegedly attempting to use a counterfeit $20 bill): “This,” Adrienne Green recently wrote for the Cut, “is what Amy Cooper wanted Christian Cooper to be afraid of.”

The everyday indignities and aggressions suffered by black Americans don’t always break through to the level of national conversation, but when they do, white women in this country are presented with an opportunity that, time and time again, we’ve failed to take: owning up to the ways in which we benefit from, and actively promote, white supremacy, and pledging to do the work of unlearning harmful behaviors so that we may commit ourselves to the project of racial justice. Will we rise to this occasion with the urgency and dedication it deserves, or will we once again seek shelter from our culpability by indulging in (and continuing to weaponize) our sense of self-preservation and victimhood?White women have actively participated in the disenfranchisement, assault, and murder of black people.

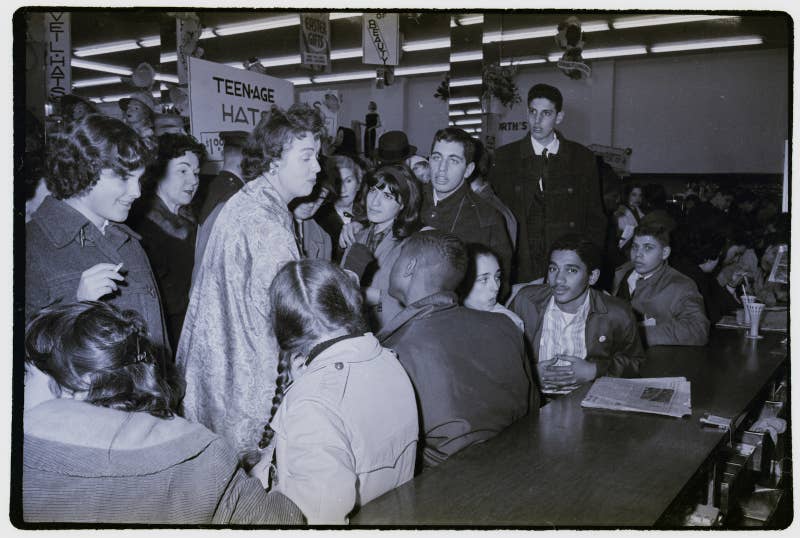

For centuries, the white damsel in distress has been “protected” from the black man deemed predator by various means of state-sanctioned violence. But while white women might claim otherwise, they haven’t merely been a tool wielded by white patriarchs. They have, in fact, actively participated in the disenfranchisement, assault, and murder of black people. Historian Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers, in her 2019 book They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South, details how white women — who typically inherited more enslaved people than land, and therefore relied on the institution of slavery as their primary source of wealth — could be just as brutal as their enslaving male counterparts. Despite women’s real power under white supremacy, however, the cult of the poor, defenseless white damsel has lived on for generations. Concerns over white women’s purity and fragility made way for, among other things, race-segregated and gender-segregated public bathrooms, whippings, lynchings, and mass incarceration.

Ruby Hamad, author of the forthcoming White Tears/Brown Scars: How White Feminism Betrays Women of Color, wrote for the New York Times this week that Amy Cooper is the latest example of the damsel archetype in action: She offers “an illusion of innocence that deflects and denies the racial crimes of white society.” And yet, Hamad warns, “we should be wary of individualizing [Cooper’s] behavior by punishing her to the extent that she is deemed an outlier. Doing so obscures the racialized social context in which this incident occurred.”

Cooper has been fired from her job at an investment firm, and she voluntarily relinquished custody of her dog after facing criticism for how roughly she handled the cocker spaniel during the altercation. Some, including local leaders, are calling for her arrest for filing a false police report. Whatever consequences she faces on an individual level, however, Cooper is destined to become a symbol. She’ll be an example of cancel culture run amok in a society where being called a racist is often deemed a greater crime than actual racism, or else a cautionary tale for well-meaning white people who either shun and begrudge her for saying the quiet parts out loud.

Because for so many white people, racism is only bad enough to warrant condemnation when it’s made too explicit to ignore. A visual that’s been going around on social media this week, attributed to the Safehouse Progressive Alliance for Nonviolence, offers a helpful framework: overt acts of white supremacy, like hate crimes and racial slurs, are widely considered to be socially unacceptable, while countless more covert acts are deemed perfectly fine.

So many of those more insidious strains of racism, from discrimination in housing and education to the promotion of respectability politics to white paternalism in lieu of cross-racial solidarity, have white women at the helm, often on behalf of their white children. Who would fault a mother for wanting whatever’s best for her kids? When white parents successfully protest against the desegregation of public schools — even now, 66 years after Brown v. Board of Education — they’re likely to be applauded for standing up for their families, rather than shamed on social media. Likewise when wealthy white parents buy their children’s ways into elite universities through expensive test prep and transcript-padding gap years at boarding schools. But when celebrities like Lori Loughlin and Felicity Huffman cheat to get their kids into those universities, they’re shunned. The main players of the infamous college admissions scandals weren’t really doing anything wildly out of the ordinary from other elite-class white parents, who love taking advantage of things like legacy admissions (effectively affirmative action for the wealthy) while also decrying race-based affirmative action programs as discriminatory and unfair. But they pushed the boundaries ever so slightly, and they got caught.

We’re slowly starting to see these more covert efforts to uphold white supremacy in pop culture. Hulu’s recent adaptation of Celeste Ng’s bestselling book Little Fires Everywhere sees Reese Witherspoon in her new favorite role — well-meaning but thoroughly problematic white lady — as a mother whose obsessions with projecting the image of a perfect family, and patronizing, microaggression-laced interactions with the black woman who’s just moved into her rental property, lead to disastrous consequences. In another new Hulu effort, Mrs. America, a historical-fiction series about the fight for the Equal Rights Amendment, Cate Blanchett as Phyllis Schlafly carries out her tirade against feminism on behalf of white, well-off housewives like herself — though you wouldn’t necessarily know how deeply racism animated her battlesfrom the show alone.

When racists in the popular imagination range from men in Klan hoods to working-class white hillbillies who must not know any better, middle-class and wealthy white women can shield themselves from claims of racism by pointing out their own respectability. “I’m not a racist,” Amy Cooper told CNN. And plenty of people will believe her — perhaps she was only having a bad day, and she’s probably a liberal, after all! It’s easy enough to shirk the label, regardless of the evidence; the president insists he’s not one either, though fully half of Americans believe him to be racist (with divisions falling, of course, along party lines). The only reason so many people feel comfortable giving him the label where they might not have for his predecessors is because he’s a top offender of saying the quiet parts out loud, vocalizing what more respectable presidents thought (and acted on) in private. White women and men, across socioeconomic classes and up and down the political spectrum, from civilians to the world’s most powerful, are all capable of racist thoughts and deeds.

That’s why we need to retire the idea that racist is either something you are or aren’t, no matter how polite and subtle you are about it, and no matter your progressive bona fides. As author and historian Ibram X. Kendi puts it, there’s no such thing as being “not racist,” because the inaction implied in the face of racism is itself a form of racism. Rather, there is only racism and antiracism — the latter being active, emotional and intellectual participation in combating racism in all its forms. As Ta-Nehisi Coates has written, “ending white supremacy does not merely require a passive sense that racism is awful, but an active commitment to undoing its generational effects. Ending white supremacy requires the ability to do math — 350 years of murderous plunder are not undone by 50 years of uneasy ceasefire.”

One of the ways in which some white women avoid the work of antiracism is by crying sexism whenever they’re asked to do better. This year has seen the rise of the “Karen” meme, which is a convenient shorthand for white women with big “I need to speak with the manager” energy. Karens are the women who go viral for prioritizing their own comfort ahead of other people’s, often by racist means: those who refuse to wear masks during the coronaviruspandemic, who call the cops on black people enjoying everyday activities like barbecuing in the park or selling drinks on the street. They’ve had a variety of names over the years — BBQ Becky, Permit Patty — and now they’re all at home under the wide umbrella of Karen, where they can receive the scorn they deserve. Of course, both men and women have complained that the meme is sexist, and there have certainly been instances of “Karen” being deployed in sexist ways. But the fact is white women don’t need to be called “Karen,” or even provoked in literally any way, to spin themselves into hysterics and claim they’re being threatened or oppressed.

Black feminists like Audre Lorde have long warned us: Standing on the backs of black and brown women won’t make us any freer, because until we are all free, none of us are.

The pushback against the Karen meme is yet another way in which white people tend to prioritize ideals of civility, peace, and decorum over the messy work of confronting racism’s everyday evils. To merely call attention to racism and bigotry, even in calm and productive ways, is often framed, especially by the right-wing media, as a vicious and hateful attack. (Think about the absolute uproar after the cast of Hamiltonaddressed Vice President Mike Pence when he came to the show in 2016, welcoming him and expressing concerns about his administration’s plans to protect minorities, children, and the planet — Trump, and many others in his orbit, deemed it harassment.) The limits of respectability politics are made clear when even “good” victims of racism, like Christian Cooper (an enthusiastic birder and longtime LGBTQ activist who graduated from Harvard) are treated in the same dehumanizing and racist ways as those without the markers of class and status that might make white people more comfortable. “Respectability” seems like an empty promise when gun-toting white protesters railing against state shutdowns and mask orders can scream in cops’ faces and go home unscathed at the end of the day, while protesters in Minnesota over George Floyd’s death were met with police in riot gear brandishing tear gas and rubber bullets.

For the white women of my generation — who were raised in the confusing swirls of the whore/virgin complex, and encouraged to be independent while also docile, submissive, and attentive to the needs of men — being respectable, a “good” girl, can seem like a kind of freedom. Maybe if we are “good” (thin, pretty, successful but not too successful, dutiful foot soldiers in the fight to maintain white supremacy — but quietly, don’t be a Karen!) then we can survive the machinations of the capitalist patriarchy. But being “good” won’t save us from misogyny or abuse, or from the harmful austerity of capitalism. Black feminists like Audre Lorde have long warned us about that: Standing on the backs of black and brown women won’t make us any freer, because until we are all free, none of us are.

I thought about what it means to be a “good” representative of a marginalized group when the New York Times announced the death of the author and heroic AIDS activist Larry Kramer yesterday. At first, the obituary’s subheadline mused that “his often abusive approach could overshadow his achievements,” before the word “abusive” was swapped for “aggressive,” then “confrontational.” Then the wording was changed entirely; now it reads that Kramer “sought to shock the country into dealing with AIDS as a public-health emergency and foresaw that it could kill millions regardless of sexual orientation.” Even after so many harried edits, the paper still failed to accurately capture Kramer’s work, which did address the fact that AIDS could kill even those who aren’t gay, but was fundamentally rooted in the belief that AIDS only became a plague in this country because of the American government’s hatred of LGBTQ people and ambivalence to their suffering. It was precisely Kramer’s “aggressive” and “confrontational” approach — railing against the pharmaceutical companies that remain great and terrible evils to this day, especially as we’re living through another plague — that allowed him and the other unruly members of ACT UP to save hundreds of thousands of lives.

As the current pandemic is disproportionately ravaging black and communities, and as another police killing has thrown families and communities into terrible grief, now is a chance for white women to do some necessary deprogramming about what it means to be “good.” Remaining quiet, polite little girls who are “not racist” but make no active efforts to combat white supremacy — even and especially when we mess up, which we all have and will do again — because it’s too loud and messy and “aggressive” is just not going to cut it anymore. Do your research: There are plenty of free resourcesout there for white people interested in racial justice work. Donate to bail funds, like #FreeBlackMamas or this one in Minnesota, which is aiding activists jailed for protesting George Floyd’s killing. Check out mutual aid funds in your area — if there isn’t one, consider starting one! — and, if you haven’t already, work on changing your mindset from one of providing “charity” to acting in solidarity. Agitate for police reform. Speak up whenever you witness either overt or covert instances of racism, even if that means disrupting social scripts for “good” white women by making other white people uncomfortable. Hold yourself and other white people to account. Decenter your own feelings. Refuse to be a damsel. Work toward a world where being “good” doesn’t mean being calm and quiet in the face of injustice, but having the courage and the commitment to make noise.