“I’m changing my patterns because I can’t change the color of my skin,” the founder of a running group said.

Every time Edward Walton laces up his running shoes, no matter where he is, there is a calculus he takes into consideration: What time of the day is it? What neighborhood will I run in? What am I wearing?

And when he’s outdoors, he says, it adds up again: Am I running too fast? Does it look like I’m fleeing from someone?

“It’s the math,” Walton, 51, a cybersecurity architect and consultant in metro Atlanta, said, “of running while black.”

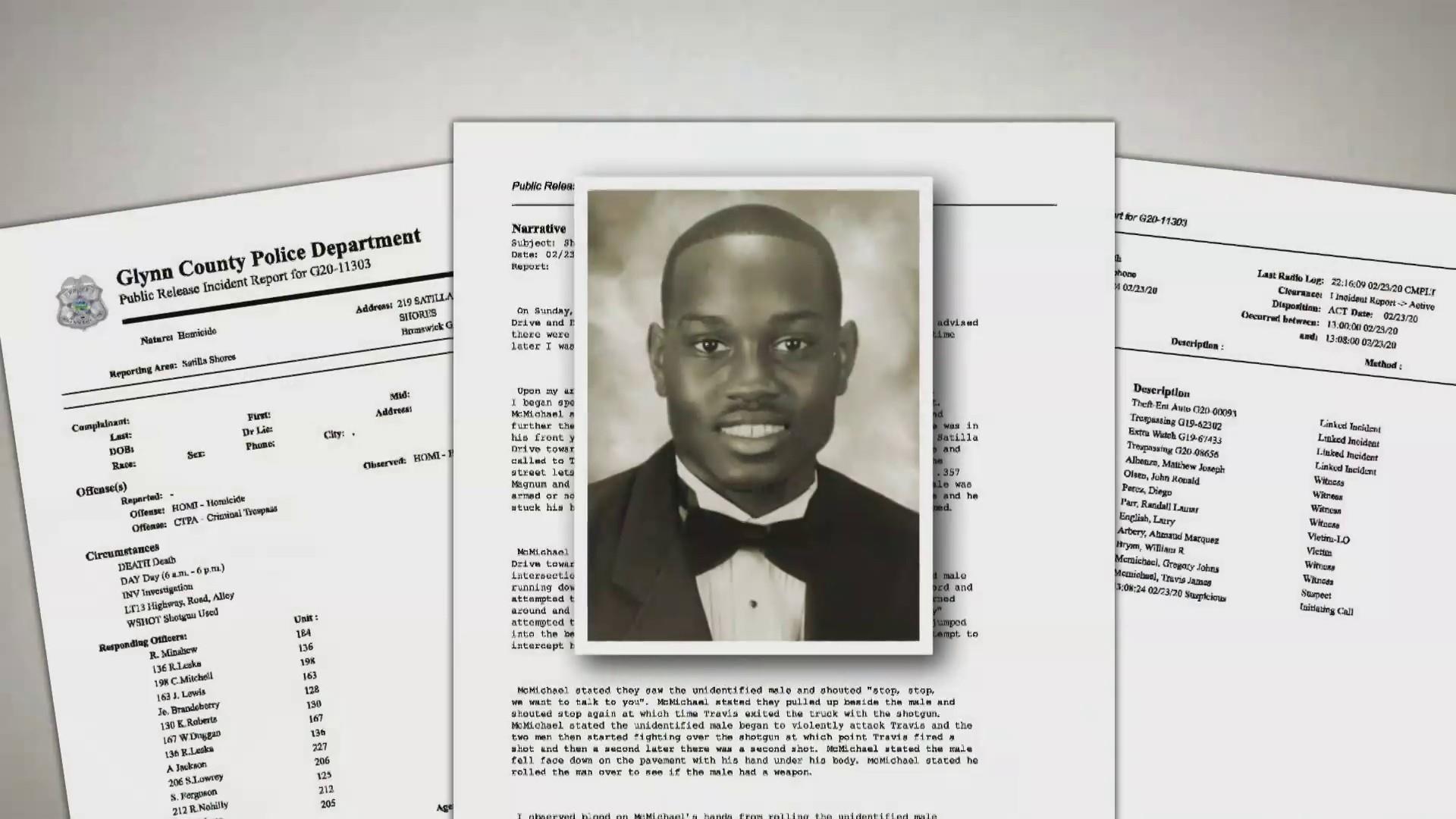

The killing of Ahmaud Arbery, a black man who his family says was out for a jog when he was chased and fatally shot by two white men in late February, has renewed a national conversation about racial profiling and when black Americans, in particular, are accused of criminal behavior in the midst of routine, everyday activities, such as mowing a lawn or waiting inside a Starbucks.

Arbery, 25, has been described by his family and friends as an athlete who regularly ran in his south Georgia community in Glynn County, and had plans to go back to technical school and become an electrician. While the father and son involved in his killing were arrested last week on murder and aggravated assault charges in the wake of leaked cellphone video appearing to show the confrontation, the incident has rattled people like Walton, who say the killing is an extreme occurrence of what runners like himself have long, quietly known.

“When I’m running, people give me two looks,” Walton said. “Why is this black guy running? What is he running from? What did he do?”

The suspects in Arbery’s killing, Gregory McMichael, 64, and Travis McMichael, 34, told police they were making a citizen’s arrest and believed the youth had burglarized a nearby home that was under construction. Attorneys for Arbery’s family maintain there is no evidence showing he was engaged in criminal activity on that day, other than possible trespassing on the unoccupied property. The attorneys for the McMichaels have suggested there’s more evidence yet to be made public that tells a different narrative.

“This is not some sort of hate crime fueled by racism,” Gregory McMichael’s attorney, Franklin Hogue, told reporters Friday. “It is and remains the case, however, that a young African American male has lost his life to violence.”

As the circumstances surrounding Arbery’s killing play out in the criminal justice system, black runners who spoke with NBC News said the case serves as a reminder that their lives could also be in jeopardy if they’re out at the wrong place and the wrong time.

Seven years ago, Walton co-founded a group in Atlanta called Black Men Run, which he says has grown to 55 chapters in 35 states, as well as internationally in London and Paris.

It was conceived as a way for black men, facing their own health disparities and challenges, to unite in fellowship and help one another become accountable for their physical well-being. That has become especially important now, Walton added, with the disproportionate effect that the coronavirus outbreak has had on black Americans.

But incidents like Arbery’s killing have also shifted the group’s focus to becoming more activist-driven. Last week, members participated in a 2.23-mile jog in Arbery’s honor, marking the day of his death, as part of a social media campaign. A rally is planned Saturday in the coastal community of Brunswick, Georgia, where Arbery was from.

Tobias A. Jackson-Campbell, a realtor from Atlanta who has run in four marathons, said he’s begun changing where he runs to avoid isolated places in the city, such as the undeveloped sections of the multiuse trail known as the Atlanta Beltline.

Jackson-Campbell said he’s been followed by police during his runs and questioned about what he’s doing in a particular neighborhood.

“For me, as a black man running, it’s sometimes like driving while black,” he said.

Arbery’s killing, he said, only reinforced that “if it could happen to him, it could definitely happen to me.”

Kristea Cancel, a runner from North Carolina, said she recently tracked her 13-year-old son’s run using an app because she was uncomfortable not knowing where he was. The next day, she went running with him.

She recalled how a few years ago while running in Tennessee, someone in a white pickup truck threw their drink in her face and screamed at her on a busy street in broad daylight. Nothing had been out of the ordinary until that moment, she said — it had been a routine run.

“When will it be OK to just be shopping, running, in the park and not be feared or criminalized by people who can’t just let us be human beings, enjoying life as they are entitled to do?” Cancel asked. “No mother should be worried a run or walk may end their son’s life.”

When Walton hears of how friends and others have changed how they exercise outdoors as a precautionary measure, he says he completely understands.

“I’m changing my patterns,” he said, “because I can’t change the color of my skin.”