Food—and easy access to it—is a universal right. That’s a statement we should all agree on, yet the distribution of safe and affordable food is far from equitable in the United States. Black, brown, and Indigenous communities have been subject to redlining—a practice that denied housing loans to people of color and caused grocery chains to pull out of urban areas—and other racist policies for decades, and as a result have disproportionately less access to full-service grocery stores, well-funded neighborhoods, and schools. These truths are not new. In fact, the entire U.S. food system was founded on systemic racism—and that legacy impacts the well-being of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) communities to this day.

From the early 1600s through the end of the Civil War in 1865, plantations in the South were forcibly worked by highly skilled enslaved Black people. Enslaved peoples were responsible for planting, tending, and harvesting all of the food (as well as the region’s cash crops of tobacco and cotton), yet the large majority were denied access to the fields they tended and the foods they grew. Nor did they ever benefit from the lucrative profits their labor created for their white enslavers.

After the Civil War, Black people experienced another form of violence in the form of sharecropping. Across the agricultural South, Black people would lease portions of land from white landowners in exchange for a percentage of their crop yield and were forced to accept whatever terms were set forth by the landowners, many of whom were previous slave owners. By the 1920s, there were over 900,000 Black farmers in the United States. According to data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, there are fewer than 50,000 Black farm producers (meaning someone making management decisions on farms) today. The reasons are multifactorial, including discriminatory lending practices and preferential treatment of non-Black farmers that made it harder for Black people to become autonomous farmers once the practice of sharecropping ended for good after World War II.

In addition to having fewer Black food producers, many Black communities have been excluded from curating the food options that are available within their own neighborhoods. Food, as well as access to certain foods, shapes the food culture of communities. In the 1960s, the federal government encouraged the Small Business Association to give loans to Black Americans who were then encouraged to open fast-food franchises within their communities, thus shaping the narrative that fast food is a part of Black American culture. At the same time, white flight and social unrest led many other kinds of businesses to pull out of Black, brown, and Indigenous neighborhoods—including full-service grocery stores. This left a vacuum that has been filled by dollar stores, fast-food chains, and liquor stores.

When neighborhoods are intentionally constructed to be swimming in fast and processed foods, the health of their residents suffers. Black, brown, and Indigenous people are disproportionately burdened with illness and poorer health outcomes—many of which can be connected to diet and lifestyle—compared to white Americans because of the systemic inequities that create disadvantages.

Oftentimes, there is the misconception that access to the variables that allow us to express health is equitable. This is not the case. Data tells us that the very zip code in which you live has a direct impact on your health and outcomes. Another challenge is that Black, brown, and Indigenous people tend to be diagnosed later and subsequently receive treatment later for certain diseases, resulting in poorer outcomes. Sometimes this is because patients are less likely to seek out help when they do not expect equitable care—a reality for many people of color, particularly Black women. Many times, this is because people of color are less likely to have access to consistent, high-quality care.

These factors deeply affect a person’s ability to be well. Yet, as a health-care provider, I have heard first-hand from my patients that they feel blamed for any diagnosis they have, especially the illnesses that are deemed diet-related such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease. The blame is internalized as shame—which only further impacts their health and well-being.

Additionally, the large majority of the research studies that guide health-care recommendations have study participants that are not representative of the diversity within this country. In fact, the study participants from both the Nurses Health Study and the Physicians Health Study—two massive, longitudinal research trials that are used to inform lots of health research—are overwhelmingly white and middle class. When the study participants are not representative of the diversity of the country in which we live, it’s likely that the public health recommendations derived from said research may not be accessible and generalizable to all.

In essence, we are looking at 400 years of racism and systems that have been designed to segregate and keep BIPOC communities from flourishing and being well. In order to improve the health of these communities, we must address these massive, systemic injustices. There is no expectation of solving these problems overnight, but I believe that there is a path forward that encompasses many of the recommendations made by social justice organizations and health equity professionals.

First, we must educate ourselves. Learning the history of food systems and structures and systems that define social determinants of health informs how and why we as a nation are where we are today. This list of resources compiled by a 17-year-old Black Lives Matter activist—which is updated on an ongoing basis—is a good place to start with this necessary work.

Beyond the self, our systems need to change. We need diverse voices in decision-making and leadership positions in local, state, and federal governments. Black, brown, and indigenous people not only need to be a part of the conversation, but they also need to shape the conversation.

Communities need funding to thrive, too. Reinvesting in marginalized communities is vital to systemic change. Well-funded and fully operational schools, libraries, playgrounds, grocery stores, and health-care facilities are integral to change.

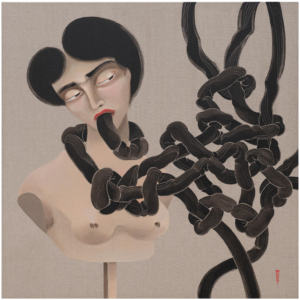

This may seem beyond the individual but it’s not. Individuals can commit to learning and advocating for structural changes in their communities. Only then can we start to truly untangle the systemic racism that has a dangerous hold on the lives and health of BIPOC communities.