A ruptured pipeline spewed crude oil into the Pacific Ocean, and it may foul ecosystems for years to come.

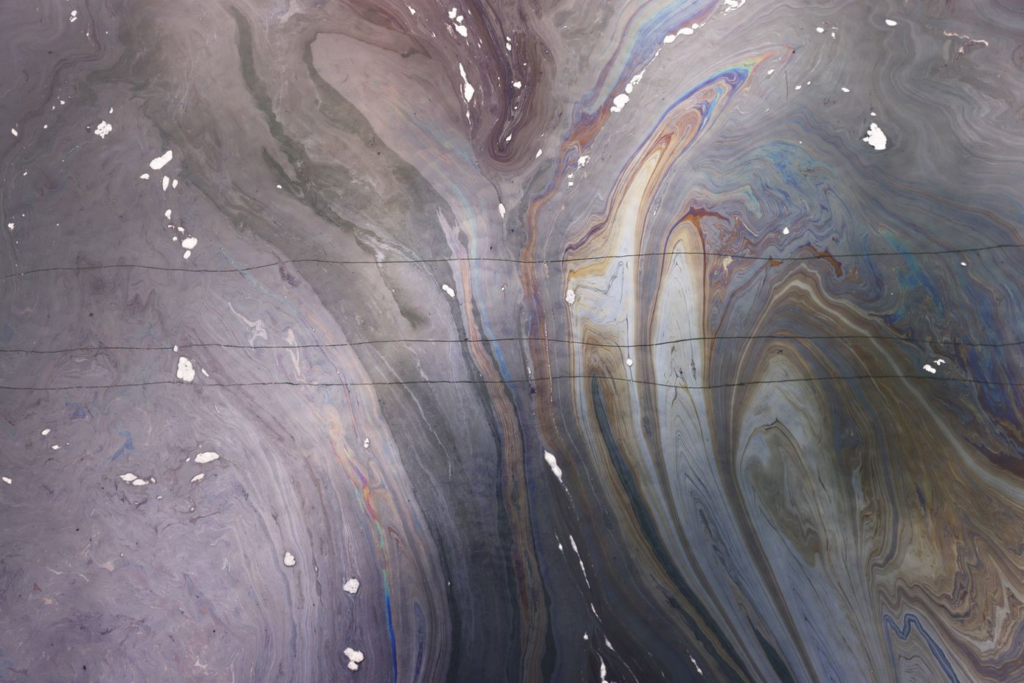

On October 2, an oil pipeline off the coast of Southern California ruptured, spewing an estimated 144,000 gallons of crude into the Pacific Ocean. The leak created a toxic, 13-square-mile oil slick off the shore of Huntington Beach, which has since spread into coastal wetlands rich in biodiversity.

While the spill is far from the scale of infamous past disasters — the BP Deepwater Horizon spill in 2010 released roughly 930 times as many gallons into the ocean — experts say it will have sweeping impacts on Southern California’s coastal wildlife, potentially for years to come.

The spill is especially bad news for birds: Every fall, millions of them migrate through the state on their way south. “It’s devastating,” said John Villa, the executive director of Huntington Beach Wetlands Conservancy, which owns and manages 127 acres of wetlands along the coast. Villa says the spill severely impacted marshes that are home to several avian species threatened with extinction, including the least tern. “A big concern is what’s going to happen to them,” he said. The conservancy is still surveying the damage.

Scientists are now racing to find and treat animals covered in oil, which can cause a range of problems from hypothermia to poisoning. As of October 4, the Oiled Wildlife Care Network — a rescue organization established in the wake of a 1990 spill that also occurred in Huntington Beach — had recovered eight birds, one of which the group euthanized due to injuries unrelated to the spill.

While birds and other animals coated in oil tend to draw attention during any spill, some of the most alarming impacts are far more subtle and occur over the long term, experts say. Oil slicks kill marine algae called phytoplankton, for example, which can disrupt entire food chains.

The spill is a reminder that our dependence on fossil fuels can cause damage even beyond the impacts of climate change, which has bolstered devastating droughts and fire seasons in California. Oil infrastructure can — and does — malfunction.

Climate change could also put offshore pipelines and rigs in the path of increasingly powerful storms, which have triggered major oil leaks in the past. Many experts say the only way to prevent leaks and safeguard the nation’s coastal ecosystems is to stop using fossil fuels altogether.

What happens when oil coats feathers, fur, and fish

While crude oil is a fossil fuel found naturally in the Earth’s crust, it’s incredibly dangerous to birds, fish, and other animals when it spills into the ocean or onto land.

For one, oil — composed of hundreds of carbon-based chemicals, or hydrocarbons — is highly toxic to animals when ingested, said Ronald Tjeerdema, an environmental toxicologist at the University of California Davis who has studied oil spills for more than three decades. During a spill, birds and mammals can take in oil accidentally through the food they eat, the air they breathe, or when preening their feathers or fur. That can cause all kinds of problems including neurological damage or cancer, he said.

Making matters worse, when oiled animals try detoxifying their bodies by breaking down the hydrocarbons, the process can actually backfire: Their bodies produce chemicals, called epoxides, that damage their DNA, said Andrea Bonisoli Alquati, an assistant professor at California State Polytechnic University Pomona. “That’s the tragedy of this response” in the body, he said.

Birds also have trouble flying when they’re coated in oil, just as we might have trouble running while wearing slick or sodden shoes. That’s a big problem for migratory species like brown pelicans and snowy plovers, two species found in coastal California. It takes them more energy to migrate if their feathers are oily, and so they need more food. One 2017 study of western sandpipers found that just a small coating of oil can delay the birds’ roughly 3,700-mile migration by as much as 45 days because of the added time it takes them to refuel at each stopover.

Oily plumage can also make birds easier pickings for predators. Another 2017 study on western sandpipers concluded that crude-covered birds were much slower during takeoff and took longer to gain altitude than their oil-free counterparts. “Slower and lower takeoff would make oiled birds more likely to be targeted and captured by predators,” the authors wrote. And oily birds aren’t healthy to eat, either.

Crude oil can even make it hard for birds and furry mammals, such as otters, to stay warm, Tjeerdema said. Essentially, fur and feathers need to be fluffy and clean to maintain their insulating properties. Oil mats them down. That’s why these animals often die from hypothermia in the wake of a spill, Tjeerdema said.

The situation is equally dire for animals that spend all their time in the water. Research following the Deepwater Horizon spill in the Gulf of Mexico — the largest marine oil spill in history — has shown that dolphins are more likely to be sick and produce far fewer offspring in areas that were inundated with crude. Oil can also poison fish that hang out by the ocean’s surface, nearer to slicks, because they absorb chemicals through their gills.

It can take years for oiled ecosystems to recover

Photos of tar-covered birds and dead fish tend to represent oil spills in the news, but much of the damage from seepage is out of sight and occurs over years or decades after the last drop enters the ecosystem, Bonisoli Alquati said.

Many fish and invertebrates, such as clams and sand dollars, start their lives as larvae, which are incredibly vulnerable to the effects of oil, Tjeerdema said. That’s why you might see a dip in their populations in the years following a spill. Bonisoli Alquati’s research has also shown that oil from a spill can make its way inland and affect land birds and other terrestrial animals. That means it’s not just mucking up creatures that live in and around the sea.

Crude oil can also kill a vast amount of phytoplankton, which feed loads of other creatures. “We won’t see a lot of dead bodies with those because they’re nearly microscopic, but we will see a hit there — and they tend to be the base of the food chain,” Tjeerdema said. Spills damage plants, too, which has similar ramifications for the broader ecosystem, Bonisoli Alquati said.

By destroying plants, spills can even make coastal areas more prone to erosion, he said, and that can lead to the “loss of the ecosystem entirely.” This played out in coastal Louisiana following the Deepwater Horizon disaster, he said. The region was already contending with intense oil and gas development, plus sediment loss in the Mississippi River and coastlines receding due to sea-level rise.

It’s important to remember that ecosystems can recover from a spill, said Tjeerdema, who explained that California ecosystems may take a few years to recover from this most recent spill. “The main point I want to make, having studied spills for so long, is that the environment recovers over time — it’s really resilient,” he said. For the most part, for example, the Gulf ecosystem has recovered from Deepwater Horizon, he said. (Not everyone agrees.)

What complicates that optimistic message is that ecosystems typically face more than just a glut of oil during a spill. Most coastal habitats are being sliced up by developers or suffering from other kinds of pollution already, such as factory runoff. The coast of Southern California is dotted with oil rigs and has already lost 62 percent of its 33,400 acres of coastal wetlands.

“Shorebirds and marine birds are already facing immense challenges from loss of habitat and climate change,” Andrea Jones, director of bird conservation for Audubon California, said in a statement. “A spill like this makes it even harder for them to thrive.”

Climate change puts oil infrastructure at risk

The California oil spill is a big deal: It occurred in a heavily populated and environmentally sensitive area, and it has prompted Democratic lawmakers in the state to renew calls for a ban on offshore drilling and the governor to declare a state of emergency. But it’s just one of a number of recent spills. In the two weeks following Hurricane Ida in the Gulf this summer, more than 50 oil leaks were reported by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Extreme storms frequently damage oil infrastructure and cause spills. Hurricane Katrina caused a series of spills that sent roughly 10 million gallons of oil into the Gulf. That’s the equivalent of 80 spills the size of the one that just hit Huntington Beach, or about how much oil leaked into the ocean during the Exxon Valdez disaster.

In other words, the oil and gas industry is fueling a problem — rapid global warming that can worsen extreme weather — that puts its own infrastructure, and potentially entire ecosystems, at risk.

To be sure, spills don’t appear to be getting more common, or more severe, according to data from NOAA. One of the most recent very large spills took place in 2010 when over a million gallons spilled into Michigan’s Kalamazoo River. “We don’t have as many catastrophic oil spills as we had 30 or 40 years ago,” Tjeerdema said. It helps that we now have safer equipment for transporting oil, such as double-hulled ships.

But our planet stands to benefit enormously if oil spills keep declining all the way to zero so that wildlife is spared their devastating effects. “We have the capacity and we have the tools to change,” Tjeerdema said. “It’s the will that is lacking.”

Update, October 6: This story was updated with a new estimate of how much oil was released by the ruptured pipeline.

Correction: A previous version of this story misstated the magnitude of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill compared to the Huntington Beach spill. The Deepwater Horizon disaster spilled roughly 930 times more gallons of oil than the Huntington Beach spill.