t a time when monument removals have sparked national debates on how to remember the past in the present, residents of one Southern city are facing an uncomfortable episode in its history head-on.

The city of Roanoke Rapids, N.C., and Halifax County are declaring Saturday, Aug. 1. this year “Sarah Keys Evans Day,” 68 years after its police arrested Sarah Keys, a 23-year-old Black Women’s Army Corps private, for refusing to give up her seat on an interstate bus for a white Marine. Fined $25 (about $240 today) for disorderly conduct, she filed a complaint that—three years later—resulted in an Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) ruling prohibiting segregation on interstate buses. A proclamation by local Congressman G.K. Butterfield recognizing Evans’ service to her country will also be presented at the ceremony, and he will submit it to the official record of the House prior to the event.

Following a grassroots campaign by local Black educators for more recognition of Evans’ contribution to American history, Saturday will also see the socially-distant unveiling of a mural illustrating her ordeal. Featuring eight panels by local artist Napolean Hill, illustrating moments in her story, it is entitled “Closing the Circle.” It symbolizes the city’s coming around to recognition of her brave stance, says Charles E. McCollum, chair of the Sarah Keys Evans Inclusive Public Art Project.

“I didn’t know about [Evans] until a few years ago,” says Vernon J. Bryant, chairman of the Halifax County Board of Commissioners. “It’s important that we recognize people in our backyard. Whether it’s good history or bad history, it’s history.”

“It’s a proud moment,” says Krystal Hargrave, Evans’ great-niece. “The community prioritizing honoring her during these really uncertain times goes to prove just how important her contributions were. The mural is a symbol of hope, and for the Black community, a way to have a voice.”

Evans, who took that name after she married in 1958, is 91 and living in Brooklyn, N.Y. She cannot attend in person, but her niece Julie Ann Graves, who lives nearby in Chapel Hill, will be representing the family.ADVERTISING

Reached by phone in the walk-up to the ceremony, Evans tells TIME she sees the monument as a tribute not only to her but also to all of “the women who have been left out” of the 1950s and 1960s chapter of the civil rights movement.

“Black and white women kept the spark going, and I don’t think they’ve been given enough credit,” she says. “Each of us have our own story.”

‘I cried and I prayed’

On Aug. 1, 1952, Sarah Keys boarded a bus from Trenton, N.J. to her home in Washington, N.C.—her first visit home since joining the military. When the bus stopped in Roanoke Rapids shortly after midnight to change drivers, the new one told Keys to give up her seat for a white Marine. She refused. Everyone had to get off the bus, and he let everyone get on another bus, but not Keys. Two policeman took her by each arm and escorted her to a police car. Jailers put her in a cell with a mattress so dirty she was afraid to sit down, so she stood all night in full uniform, including her one-and-a-half-inch heels.

“I paced the floor all night, and I cried and I prayed,” she said in a video that was recorded as part of the effort to get a grant to fund the mural. “What is happening to me? What am I going to do?”

She was released the next day and fined. When she got home, her family—who had had no idea where she was—was shocked to hear what had happened. “Sarah was the quietest of us all. This happens to Sarah?” says her sister Cornelia Hargrave of the family’s reaction.

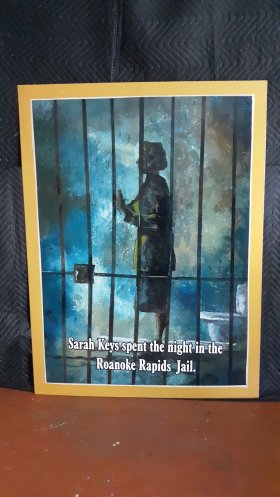

Her father encouraged his daughter to take legal action. After all, in 1946, the Supreme Court had declared state laws enforcing segregation on interstate buses unconstitutional, in Morgan v. Virginia, though a loophole allowed private companies to make their own rules. TIME reported back then that the Justices “ducked the racial question and settled everything on the basis of comfortable traveling.” The NAACP referred the Keys family to attorney Dovey Roundtree, who filed a complaint with the ICC on her behalf. It was initially dismissed by an examiner, but Congressman Adam Clayton Powell persuaded the full commission to hear the complaint. In artist Napolean Hill’s studio, a panel in the new mural shows Private Keys in a Roanoke Rapids jail cell in the wee hours of Aug. 2, 1952, after refusing to give up her seat on an interstate bus to a white Marine. Courtesy of Napolean Hill

In artist Napolean Hill’s studio, a panel in the new mural shows Private Keys in a Roanoke Rapids jail cell in the wee hours of Aug. 2, 1952, after refusing to give up her seat on an interstate bus to a white Marine. Courtesy of Napolean Hill

In the new mural, the first panel portrays a beaming 23-year-old Keys in her Women’s Army Corps uniform. The following panels show the bus pulling into the Roanoke Rapids bus station; her arrest; her time in her cell; her father’s role as “her greatest supporter for justice;” the setbacks she faced; and Roundtree and Powell. The eighth and final panel illustrates the ICC’s Nov. 7, 1955, decision banning segregation on interstate buses.

In Sarah Keys v. Carolina Coach Company—which also responded to a NAACP case challenging segregation on trains and terminal waiting rooms—the ICC ruled:

We conclude that the assignment of seats in interstate buses, so designated as to imply the inherent inferiority of a traveler solely because of race or color, must be regarded as subjecting the traveler to unjust discrimination, and undue and unreasonable prejudice and disadvantage.

By this point, the woman at the center of the case was out of the military and working her dream job as a hair stylist in Harlem. “It is a big relief to have it behind me,” she told the New York Times back then. “My father encouraged me when I needed encouragement.”

“The name of Sarah Keys,” wrote New York Post columnist Max Lerner, “is now added…as a symbol of a movement that cannot be held back.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

The road to recognition

And yet, what came after was far from the sunshine with which the new mural concludes. Sarah Keys’ story may have ended, but the fight to end segregated travel reached a new level of national attention when, six days after the ICC decision was made public on Nov. 25, 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat to a white passenger, catalyzing the year-long Montgomery Bus Boycott. The ICC didn’t enforce the Keys decision until 1961, amid attacks on Freedom Riders who rode interstate buses to raise awareness about segregation. As Roundtree summed up in her biography, “It was in the end not simply bloodshed or mass protest or fear that brought the promise of Keys to fulfillment. It was shame.”

And while Americans today enjoy the fruits of Sarah Keys Evans’ persistence, hers is not a household name the way Rosa Parks’ is, and she has chosen to stay out of the spotlight. Reliving the traumatic events of 1952 has become too emotionally exhausting.

Others who have tried to make her better known have hit roadblocks too.

In 2001, author Amy Nathan had stumbled upon Evans’ name on a plaque at the Women’s Memorial in Arlington, Va., and thought her story would make a great book. But about two years of interviews later, in 2006, Nathan couldn’t find a publisher. “Several editors said to me, ‘We already have a book about Rosa Parks, so that sort of covers the topic,’” says Nathan. “So it’s a catch-22; she’s not heard of because nobody has written a book about her, but then they can’t write a book about her because nobody has ever heard of her.”

Nathan ended up self-publishing a children’s book about Evans in 2006, the same year the U.S. Department of Justice honored Evans with a Trailblazer Award. In 2013, a story on the book in Our Heritage magazine caught the eye of Rodney Pierce, who was working for Roanoke Canal Museum & Trail. He had only recently learned about Evans himself and was struck that he hadn’t heard the story earlier, even though it took place in his own city. He flagged the Roanoke Valley Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the group presented Evans with an award in 2017, about two years before chapter members applied for and received a grant to fund the “Closing the Circle” mural from the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation. The state has also approved a sign that will explain the history that took place near the Roanoke Rapids bus station.

Pierce, now an 8th grade social studies teacher, hopes the mural will lead to more honors for Evans citywide. “This [mural] is the least bit you can do to finally put to rest the ugly period in the history of your city. There’s more the city could do. They could make an apology, send her a check for the $25 fine she paid, work with the local school district to get her story incorporated into the curriculum,” he says. “You can’t change what has already happened. You’ve got to embrace it and try to make it right. And this is an ideal time to do it.”

Speaking to TIME, Evans says she knows change takes time, but she’s skeptical of whether protests on the streets will lead to substantive policy change anytime soon.

“There will always be a movement of some sort,” she says, but argues today’s movement doesn’t seem to rise to the level of being called a civil rights movement. “I think grandmothers in years past had more advice than anyone you might have listened to [today]. ”

So what’s her advice?

“Keep on reading,” she says, “and keep on listening.”